Yesterday, 23rd April 2018, was the 402nd anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare and whilst we don’t have his date of birth, he was baptised 454 years ago on 26th April 1564 so this is a good week to look at his works. Monday was also the UNESCO recognised International World Book Day, as not only did Shakespeare die on the 23rd April 1616 but that is also the date that the great Spanish author Cervantes died and that is why the 23rd April (also St. George’s day) was chosen. Although they died on the same date, they didn’t die on the same day, Cervantes was 10 days earlier. Catholic Spain had already adopted the Gregorian calendar by then, however protestant England was still using the Julian calendar so there was a 10 day difference in dates between the two countries.

It may come as a surprise to most people but there isn’t a definitive version of most, if not all, of Shakespeare’s plays. The plays were documents under constant review as performances took place during his lifetime and numerous copies have survived until today. This means that modern performances can pick and choose sections from versions of the play being produced to create a suitable text for their needs. Also several of the plays are very long so now it is rare to see them performed complete, especially with falling audience attention spans. Some of the plays were published whilst Shakespeare was alive, but that was not through his doing and these are quite often inaccurate as either they were taken from actors notes or in extreme cases written down from memory by somebody in the audience. This means that we could easily have ended up with no accurate record of Shakespeare’s works at all if it wasn’t for two members of his main group of players John Heminges and Henry Condell.

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men later renamed The King’s Men in 1603 after James I came to the throne, were Shakespeare’s main troupe although other groups of actors are known to have performed his works. However these men worked most closely with Shakespeare and he was also an actor in the group so they knew his works intimately. Heminges and Condell along with Shakespeare are three of the nine men included in the Royal Patent that formally named the players The King’s Men so were significant individuals and good sources for the plays. The book is called the First Folio because it was the first edition of any of the plays to be printed folio sized, i.e. much larger than the quarto editions of individual plays that had appeared up until then and as said above were notoriously unreliable. A good example of this between a ‘bad quarto’ one probably written down by an audience member; a ‘good quarto’ one taken from actors notes or performance copies; and the First Folio can be seen here.

There are a total of 36 plays included in the First Folio out of the 38 existing works nowadays accepted as being by Shakespeare, ‘Pericles, Prince of Tyre’ and ‘The Two Noble Kinsmen’ are missing from the book. Both of these are regarded ny modern scholarship as collaborations rather than entirely by Shakespeare which may explain their absence. Eighteen plays had been published before the First Folio, however a few of these are notoriously unreliable so this was effectively the first appearance in print of over half of Shakespeare’s works and this was 7 years after his death. His modern reputation almost entirely relies on this single publication which perpetuates his work in a way he would never have expected especially due to his own reluctance to publish and therefore make his work available to other companies.

An original copy is worth a small fortune, one sold 12 years ago for £2.8 million and it must be worth considerably more now, so I clearly don’t own one of those. But mine is a lovely copy, quarter bound in leather, of the second edition of the Norton Facsimile. This volume was created with the assistance of the astonishing Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. which holds 82 out of the known 235 copies of the First Folio. Each page was selected as the best example (or sometimes the least worst) from their enormous collection. One of the major problems is the amount of show through the pages where you can read the type on the other side of the page through the side you are looking at and this made photographing the works for this edition especially difficult. Also it was decided that where possible the most correct version of the text was used as it was known that the original book was corrected during printing back in 1623 so copies vary as they were produced.

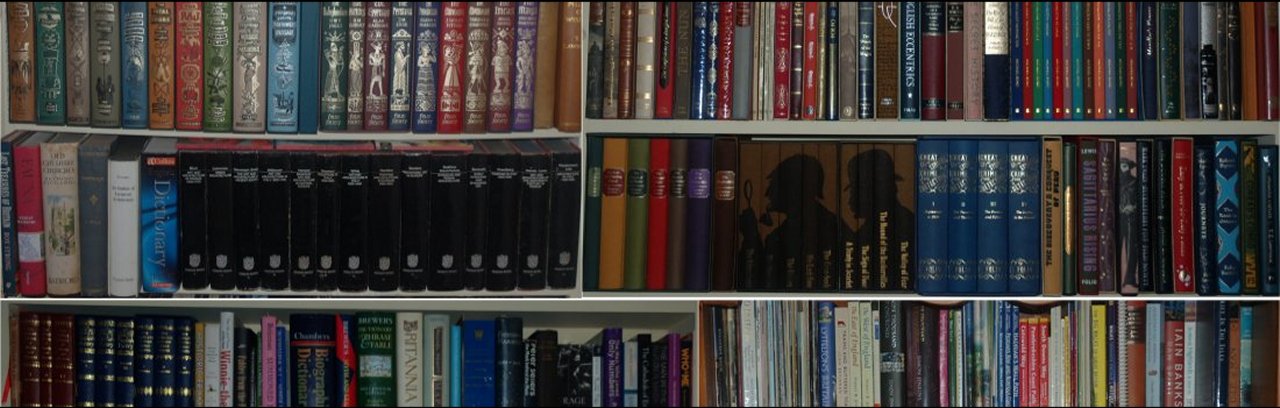

As such the reproduction is remarkably legible and easy to read and makes for interesting contrasts with my other versions of Shakespeare’s texts, two complete sets and three partial sets where the plays are in individual volumes. Some of these will be covered in later blogs especially the amazing Folio Society Letterpress Edition, probably the finest edition of Shakespeare ever printed, and certainly one of the most expensive at £295 per play. The introduction to the second edition is surprisingly dismissive of the scholarship that led to the first edition pointing out several errors. It is interesting to note that a third edition is in progress and it is hoped that the editor of that work will be kinder to their predecessors.

Seen above is the opening of The Taming of the Shrew, a play I fell in love with when I was very young and the first Shakespeare play that I bought a copy of when I just 11 years old. I still have that book in which I wrote my name, year and form name at the front of so I must have taken it to school at some point, which is how I know I was that young when I bought it. On that basis The Taming of the Shrew seems a good place to mark the end of this first essay of mine on Shakespeare’s works and I look forward to examining other editions I have in future writings.

as for the title of this essay, that is explained in First Folio 1