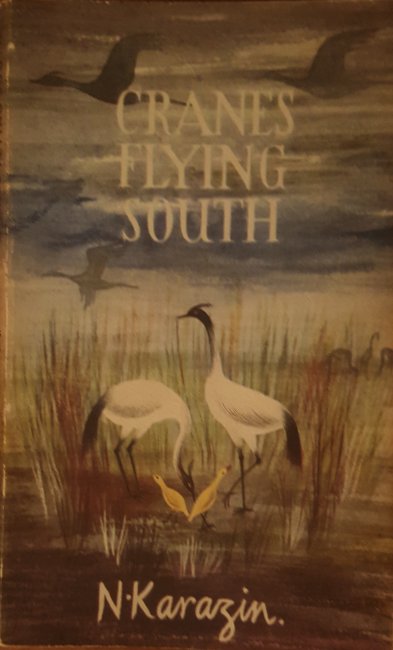

I knew nothing of this book or indeed its author before I picked up this copy a few days ago and there are no biographical details within the book either so onto the internet. Nikolay Karazin was a Russian soldier, artist and author of several books who was born in 1842 and died in 1908, he wrote and painted after retiring from the army and it is for his artwork that he is probably best known nowadays. I suspect the cover illustration is by him although no artist is credited. The English translation, by M.Pokrovsky, of his children’s book Cranes Flying South was first published in 1936 and this is the 1948 Puffin first edition. The book tells the story of the crane’s migration from the Ostashkovo marshes in north western Russia about halfway between Moscow and St Petersburg all the way over eastern Europe and Egypt following the Blue Nile to beyond Khartoum in Sudan, told from the point of view of a bird making his first long distance flight, as the book starts with him and his sister hatching.

His father, Clarion Trumpeter, is quite senior in the military like hierarchy supposed by Karazin to be normal in a colony of cranes especially during the migrations and in this he imposes his background. The story has them flying in structured triangles, which indeed they do, but regarding the stops on the way as camps with posted sentries and the discussions between senior cranes as to the best way to advance is rather more fanciful but does make for a good story. Amongst the other major characters is the Trifler, a crane known for his outrageously tall tales of his adventures and the leader of the colony Longnose the Wise. We never learn the name of our narrator or his sister, or indeed their mother but we are introduced to some of the cranes from another colony based in the Urals who join up as part of the massive flock taking part in the migration. On the way they also meet herons and storks both of which are regarded as inferior to the cranes, herons for their appetite as they will eat pretty well anything unlike the largely vegetarian cranes and storks for their relationship with man whilst cranes regard men as dangerous.

The journey south is full of incidents both with men hunting and also with bad weather which causes the loss of several cranes over open water when they get so exhausted by the buffeting winds but can find nowhere to safely land as cranes cannot swim. The descriptions of the route are also fascinating both the long slow journey over Russia and Ukraine then onto the mouth of the Danube before deciding to either cross the Mediterranean via a rest stop on Cyprus or skirting the coast from Turkey, Syria and Lebanon on their way to the Nile delta. Karazin had clearly read up on the ornithological knowledge at the time regarding the routes taken by cranes which seems to be largely correct according to the data I can find online. One particularly fun bit is near the end:

There are unimaginative persons unable to rise above the commonplace, who are generally very fond of ‘investigating’ things.

I am quite certain that several such persons, on reading of my travels will say: ‘How could he write it, when cranes have no ink and no paper?’

Such a remark will show, to say the least, a total lack of humour.

The book follows the full migration both to and from Sudan back to the breeding grounds in the Ostashkovo marshes and we get the full circle of life with our narrator pairing up with Blackneck, a crane originally from the Ural colony, and them having their own chicks. Sadly the book appears to be out of print but is quite easy to find second hand, it’s a lovely children’s story and worth seeking out.