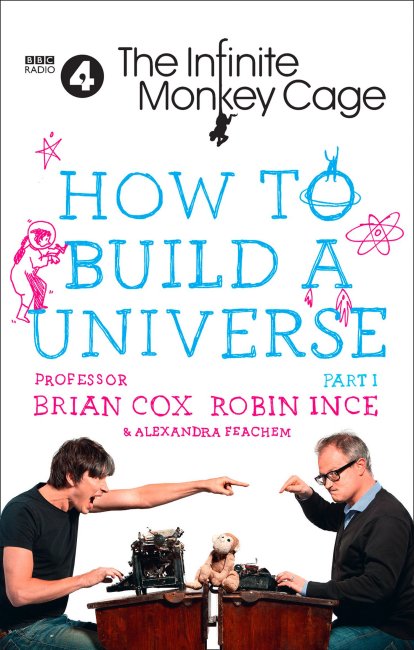

Based on the highly successful BBC Radio 4 series ‘The Infinite Monkey Cage’ this is science book like no other I have read. The radio show is also difficult to explain to people that haven’t listened to it, and you definitely should listen to it (link at the end of this blog) because it is co-hosted by on the one hand a Professor of Particle Physics at Manchester University and on the other a stand up comedian which is an extremely unlikely combination but works brilliantly. The look of the book matches the slightly anarchic structure of the radio show which in an early episode whilst discussing something completely different wandered onto the subject of “is a strawberry alive or dead?” They have come back to this subject on other occasions and I was pleased to see this being treated in the book as shown below:

The science for the most part is not overly challenging and the only really complex section is the largest, an eighty page chapter entitled ‘Recipe to Build a Universe’ which is almost entirely written by Brian Cox and as Robin writes:

This is the hard bit of the book. You may need a pencil to underline sections or just to occasionally jab into your leg or skull as you ask “but what does it all mean?” Don’t let this put you off

Page 80

In truth I have read so many books on this topic that it was relatively easy to follow and I largely sailed through this bit as it is so well written. Although a background of nuclear physics, coincidentally at Manchester University although six years before Brian went there to do his degree, possibly also helped. It also helped that the book is actually very funny especially during interplay between Cox and Ince, I laughed out loud at several sections and particularly a part written by Robin with increasingly irritated footnotes correcting him by Brian.

Other topics covered include the concept of infinity, space travel, the ultimate death of the universe and lots of things in between. In this way it is very similar to the radio show in that the main subject of a chapter, or indeed an episode, can be lost briefly if something interesting comes up as an aside. ‘Schrödinger’s strawberry’ (is it alive or is it dead) alluded to in the first chapter of this review is a prime case in point. You will learn a lot from this book but it won’t feel like it at the time unlike tackling something like Relativity by Albert Einstein or any of the four important science books I read one after another in August 2020. The style is easily approachable and the need for Brian to make sure that Robin is following the points as he makes them keeps the text grounded, although Robin Ince has now written his own science book ‘The Importance of Being Interested’ which I have a copy of so expect a review of that in a couple of months or so.

The radio show is just embarking on its twenty fourth series, some of the earlier ones only had four episodes but it now seems to have settled on six and all of them are available on the BBC website via this link. The shows on the site are usually the extended podcast versions rather than the original thirty (now forty five) minute broadcast. The usual format is that Brian Cox and Robin Ince are joined by two scientists who specialise in the subject selected for that episode and also another comedian who may have a science background but more often does not. A notable exception to this format, and an episode that is well worth listening to, was the astronaut special from series 22 where they were joined by astronauts Helen Sharman, Chris Hadfield, Nicole Stott and Apollo 9’s Rusty Schweickart. The book is great fun, the radio show even more so.