A 100-page manuscript by Mr. Lipsky was the basis of the 1947 film “Kiss of Death,” starring Richard Widmark, and the full novel was published by Penguin that same year.

New York Times obituary – Eleazar Lipsky – February 15, 1993

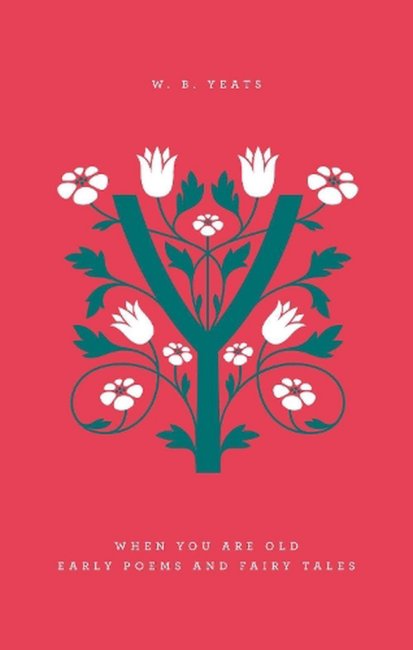

This is that first edition, published by the USA division of Penguin in August 1947, I also have the first UK Penguin edition, with a significantly less garish cover, from December 1949. see image at the end of this blog. Lipsky was by trade a lawyer and served as an assistant district attorney for Manhattan in the 1940’s, he later had a law practice in Manhattan and amongst other jobs served as legal counsel to the Mystery Writers of America. He was still practising law up to three weeks before his death at the age of eighty one from leukaemia. This solid background in law shows itself in his writing and you can be certain that the trial scenes and interactions with the Manhattan assistant district attorney in the book are procedurally accurate.

It’s an unusual crime novel as it is less concerned with the crime undertaken by Vanni Bianco and his mob then the repercussions of the act. Vanni is quickly captured and in the lead up to his trial D’Angelo, the assistant D.A. tries to persuade him to turn in the other members of his gang to avoid the mandatory thirty year jail sentence he faces for a fourth offence and this time involving a gun although it wasn’t fired during the robbery. Bianco refuses due to a code of honour and determines to do his time leaving his wife and children to be looked after by his gang. This however they fail to do and four years into his sentence word reached Bianco that his wife has died of tuberculosis brought on by cash shortages so she was looking after their daughters as well as she could to the detriment of her own health. The children were admitted into a home. This terrible situation strikes home at Bianco who determines to testify against his fellow criminals in an act of recrimination.

This is where the story totally changes tack as we follow Bianco into a new ‘career’ of stool pigeon being placed in prison cells with criminals where the D.A.’s office had insufficient evidence to see if he could get them to talk to him, an extremely dangerous role which could easily have got Bianco killed if he was suspected. It’s a very interesting aspect to the way of working of the District Attorney’s office and presumably is based on real life examples that Lipsky had during his professional career. I don’t remember reading a book dealing so specifically with the way the District Attorney would handle an informant of the type of Vanni Bianco. However I certainly didn’t see the final twist in the plot coming and it transforms the whole story in a completely believable but totally unexpected way.

As for the film mentioned in the obituary, it doesn’t really star Richard Widmark as claimed, as it was actually his debut. The film actually stars Victor Mature as Bianco and Brian Donlevy as D’Angelo with Widmark playing one of the criminals D’Angelo hopes Bianco will manage to get some more information on. I tried watching some of the movie and frankly wasn’t particularly impressed, unlike the book which was fast moving and a delight to read. It is nowadays sadly out of print but is pretty easy to track down on the second-hand market in either the USA or UK Penguin editions.