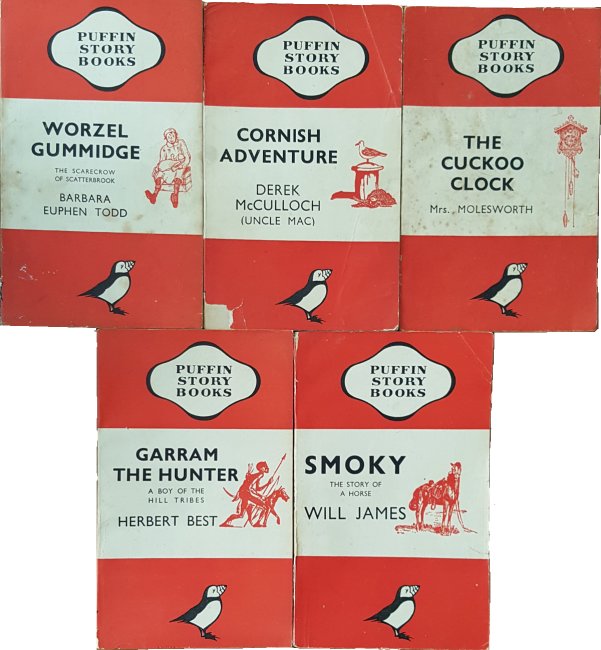

I somehow missed the eightieth anniversary of the start of Puffin Books last month as they launched in December 1941 but let’s somewhat belatedly look at how this massively important children’s imprint from Penguin Books started with five books, Worzel Gummidge, Cornish Adventure, The Cuckoo Clock, Garram the Hunter and Smoky and I have to say that the only one of these to have stood the test of time is Worzel Gummidge by Barbara Euphan Todd. I do have first editions of the Puffin books for all five so let’s take them in turn, starting each description with a quote from the title page where there is a brief introduction to the book.

Worzel Gummidge – Barbara Euphan Todd

This clever, fantastic story of the mysterious scarecrow who – when the mood took him – came to life and engaged in the funniest, and most alarming adventures, has become universally popular since the B.B.C. gave it to a wide and enthusiastic public.

The reference to the B.B.C. adaptation was a serialisation of the radio during Children’s Hour before the start of WWII and this was to just be the first of many adaptations that the book and its sequels have had over the years. I clearly remember the television version from 1979 to 1981 starring Jon Pertwee on ITV and there is a new TV adaptation running on the B.B.C. which started in 2019 starring Mackenzie Crook, which although I haven’t seen is introducing the character to a whole new generation. In the book two children, John and Susan, come to stay at the farm where Worzel is one of the scarecrows and start getting into all sorts of trouble as they are the only ones who see him move around and do things so they keep getting blamed for what he does. It’s a good story and you can see why Barbara Euphan Todd wrote nine sequels as Worzel Gummidge grew into a much loved character.

The book was first printed in 1936 and the Puffin edition is the first paperback, it is illustrated by Elizabeth Alldridge

Cornish Adventure – Derek McCulloch (Uncle Mac)

The setting, of small village, rocky cove and smuggler’s cave, is ideal for the plot that develops. The mystery breaks into the peaceful picture as the boy sails home on August morning with his fisherman friends

Derek McCulloch was best known as Uncle Mac on BBC radio where he presented Children’s Hour for seventeen years from 1933 but was also head of children’s broadcasting for the corporation throughout that time so would have been extremely familiar to his readers. It’s a classic children’s adventure yarn along the lines of Enid Blyton’s Secret Seven or Famous Five stories although these appeared much later than Cornish Adventure. ‘The boy’ referred to in the introduction is Clem and he is fifteen and has been coming to Cornwall through the summer holidays for the last five years and has got to know the local people over that time. He was out with a couple of fishermen collecting the crab pots when he spotted a dinghy going into a cave in the cliffs where they had never seen anyone before, what were the people doing there? Clem is determined to find out especially after swimming into the cave and finding it went back quite a way in the dark but he didn’t see the dinghy or the men.

The book is illustrated with drawings based on McCulloch’s own photographs but the artist who turned them into simple line drawings is not identified, it was first published in 1937.

The Cuckoo Clock – Mrs Molesworth

Griselda was only a little girl when her mother died, and she went to live in a big house with two great-aunts… She might have been lonely but for the cuckoo in the clock.

First published in 1877 and to my surprise still in print although no longer with Puffin, this book is definitely aimed at the younger reader; Griselda’s age isn’t given in the book but I’d guess at six or seven and Phil, the boy she meets near the end, is even younger and it is reasonable to assume that the target audience is around the same age as the protagonist in this case. Despite that it was a fun read with Griselda making friends with the cuckoo in the clock in scenes that could be interpreted as dreams except for the small invasions into real life afterwards such as finding the shoe from the land of the nodding mandarins in her bed (a large oriental cabinet in the room by the cuckoo clock turns out to be a gateway to where the carved figure live) or getting a message to Phil that she won’t be able to meet him the next day. The book is illustrated with several charming drawings by C E Brock.

Garram the Hunter – Herbert Best

Garram the boy is a fine vigorous character, cool-headed, bold and resolute, a skilful hunter, calculating his chances well and leaping swiftly into action. His adventures are lively and sometimes terrifying.

I probably enjoyed this book the most of the five I have read this week so it’s a disappointment to find that unlike the others it is long out of print with the Puffin version being the last I can find. Garram is the son of the chief of his tribe and is falsely accused of stealing and selling goats from one of the village elders by a rival for his fathers position. He manages to prove that the goats were in fact taken by a huge leopard but although this saves him at the time his enemy Sura continues to plot against both his father and him. Ultimately he is persuaded by The Rainmaker of the tribe to leave in order to protect his father as Sura would then fear his return as an adult to avenge any attack and so begins his adventures in lands beyond his tribes domain heading for the famous walled town of Yelwa, which is a real place, and where Garram would make his career before returning to his tribe and defeating his fathers rivals years later.

Despite being an American Herbert Best worked as an administrative officer for the British Civil Service in Nigeria and published several children’s books. First published in 1930, Garram the Hunter was shortlisted for the Newbery prize in 1931, the Puffin edition is illustrated with lino-cuts by Erick Berry which were ‘made on the spot’ so presumably in Nigeria and are the same as those in the hardback first edition rather than new illustrations for the Puffin book.

Smoky – Will James

Smoky is the story of a wild horse, told with exceptional vividness. It is also a real hot cowboy yarn, a grand adventure story told by a man who had lived in the saddle almost since infancy.

Well with an introduction like that who could fail to be intrigued? It is at many times a sad and yet ultimately fulfilling tale as Clint, who first trains Smoky after capturing him as a wild horse loses him to a horse thief. Smoky however, whilst perfectly obedient to Clint, will not allow the thief to ride him and is beaten repeatedly until eventually he lashes out and kills the thief. So begins his next life as an un-rideable bronco horse under the name of Cougar which eventually leads to career ending injuries. Sold off, this time as Cloudy he end up with yet another abusive owner who neglects and starves him before being spotted and recognised by Clint who eventually gets him back and nurses him back to health and a quiet retirement. Yeesh it was a hard read for a lot of the time.

Smoky is illustrated by the author although he isn’t credited in the book and it is easily the longest of the books in this set of five at 192 pages. Smoky won the Newbery medal for American children’s literature in 1927, a year after the book was first published, much to the surprise of Will James who considered it a book for adults, probably assuming the hard life Smoky has to be too upsetting for a younger readership.

Eleanor Graham was the series editor for Puffin Books from 1941, when they started, through to 1961 when she retired and was replaced by Kaye Webb. She did a remarkable job, especially dealing with paper rationing during the war and then building the imprint once paper started to become more available in the early 1950’s and adding titles such as Heidi, The Borrowers stories by Mary Norton and the first Moomin book. Webb inherited a series which by then ran to 150 titles which she was to vastly expand during her time in control including creating the Puffin Club and its associated annuals.