William McGonagall has gone down in history as the worst poet in the world and this book is a collection of almost every poem that can be reliably attributed to him. These have been published in various collections, but Duckworth have produced the most complete versions admittedly by creating extra volumes by merely selecting from the few books and pamphlets printed in the 1800’s along with some previously unpublished works. This book appears to combine an existing seven volumes into one but only two volumes were produced in McGonagall’s lifetime along with lots of single sheet poems sold as he was going along. In reality four of the listed volumes were created by Duckworth in the 1980’s and the three others were considerably shortened by them at the same time in order to provide works for the extra books.

I think we need an example from his first collection printed in 1890 just so that the uninitiated can get the measure of the man’s genius, this was his first poem, dated 1877 and is entitled “An Address to the Rev. George Gilfillan”

All hail to the Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee,

He is the greatest preacher I did ever hear or see.

He is a man of genius bright,

And in him his congregation does delight,

Because they find him to be honest and plain,

Affable in temper, and seldom known to complain.

He preaches in a plain straightforward way,

The people flock to hear him night and day,

And hundreds from the doors are often turn’d away,

Because he is the greatest preacher of the present day.

He has written the life of Sir Walter Scott,

And while he lives he will never be forgot,

Nor when he is dead,

Because by his admirers it will be often read;

And fill their minds with wonder and delight,

And wile away the tedious hours on a cold winter’s night.

He has also written about the Bards of the Bible,

Which occupied nearly three years in which he was not idle,

Because when he sits down to write he does it with might and main,

And to get an interview with him it would be almost vain,

And in that he is always right,

For the Bible tells us whatever your hands findeth to do,

Do it with all your might.

Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee, I must conclude my muse,

And to write in praise of thee my pen does not refuse,

Nor does it give me pain to tell the world fearlessly, that when

You are dead they shall not look upon your like again.

Gilfillan when hearing of the poem is reported to have said

“Shakespeare never wrote anything like this.”

which McGonagall took to be a compliment. This was the also the first example of what could be called the curse of being celebrated by McGonagall as a year later in 1878 he had cause to write two more poems about Gilfillan, entitled “Lines in Memoriam of the Late Rev. George Gilfillan” and “The Burial of the Reverend George Gilfillan”. He famously wrote in praise about the Bridge over the Silvery Tay only to subsequently write less that 2½ years later about “The Tay Bridge Disaster” This latter work is a good example of the unintended humorous nature of his works by forcing lots of facts into the poem without worrying if it then made any sense whatsoever and destroying any rhythm that may have been wanted. His need in poetry was to make it rhyme not scan and as long as a tenuous rhyme was achieved he appeared to be happy.

William McGonagall was born in 1825 in Ireland but came with his parents to Scotland as a very young child, indeed he claimed for a long time to have born in Edinburgh but the family soon settled in Dundee which he where he grew up. For the first fifty two years of his life he sometimes dabbled in acting but was by profession a weaver like his father until in 1877 the poetic urge struck him

I remember how I felt when I received the spirit of poetry. It was in the year of 1877, and in the month of June, when trees and flowers were in full bloom. Well, it being the holiday week in Dundee, I was sitting in my back room in Paton’s Lane, Dundee, lamenting to myself because I couldn’t get to the Highlands on holiday to see the beautiful scenery, when all of a sudden my body got inflamed, and instantly I was seized with a strong desire to write poetry, so strong, in fact, that in imagination I thought I heard a voice crying in my ears-

“WRITE! WRITE”

I wondered what could be the matter with me, and I began to walk backwards and forwards in a great fit of excitement, saying to myself– “I know nothing about poetry.” But still the voice kept ringing in my ears – “Write, write,” until at last, being overcome with a desire to write poetry, I found paper, pen, and ink, and in a state of frenzy, sat me down to think what would be my first subject for a poem.

That he knew nothing about poetry was proved by the poem above, but whilst a poet can have a bad day, especially with their earliest works, McGonagall was if anything to get worse. There is a beauty in the total awfulness of his works that sucks the reader in, the Complete Works includes 247 poems and I have read it cover to cover several times. You just can’t believe what it is you are reading. The photo on the cover of the edition I have is of Spike Milligan as McGonagall and Peter Sellers as Queen Victoria as Milligan in particular popularised ‘The Great McGonagall’ from the 1960’s onwards and ensured that his body of work did not get neglected.

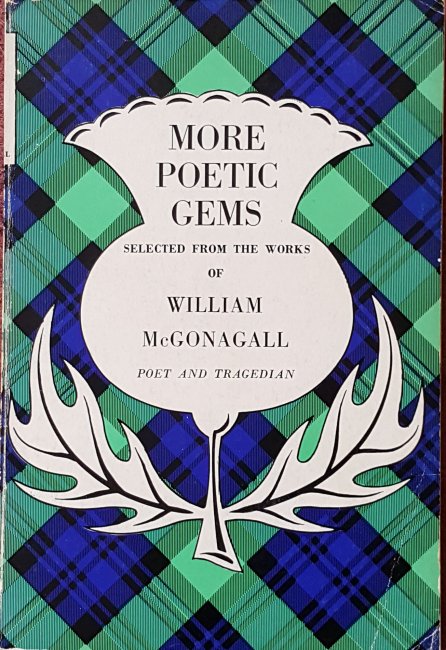

His works have been in constant print for many decades, above is the 1966 edition of More Poetic Gems published by David Winter and Sons in Dundee (who were his original publishers) and Gerald Duckworth and Co Ltd as a joint venture. Although appreciated now McGonagall died in poverty in 1902. He had eked out a living more as a sideshow than a poet from 1877 although it is clear that he regarded himself as a much put upon performer who was delivering great work to people who didn’t appreciate his ability. It was quite common for an audience to throw rotten fruit and vegetables and sometimes even fish at him whilst he was reciting, indeed the opening paragraph to the preface of his first published work ‘Poetic Gems’ includes the line

the first person to throw a dish of peas at me was a publican

It isn’t so much the fact that somebody threw a dish of peas at him as that this was just the first time…

Because he had no money when he died he was buried in an unmarked grave in Greyfriers kirkyard in Edinburgh, his grave received a nearby marker in 1999.

William McGonagall

Poet and Tragedian

“I am your gracious Majesty

ever faithful to Thee,

William McGonagall, the Poor Poet,

That lives in Dundee.”

I shall include one final poem and it’s one of the less well known ones “The Death of Captain Webb”. Webb was the first person to swim the English Channel (22 miles at its shortest point). He is something of a local hero here in Shropshire as he was born less than 5 miles from where I am sitting but died in a somewhat foolhardy attempt to swim across the rapids below Niagara Falls. The poem shows McGonagall at his prime, it was written in 1883 and has all his stylistic failings…

Alas brave Captain Webb has acted the part of a fool

By attempting to swim the mighty Niagara whirlpool,

Which I am sorry to say and to relate,

Has brought him to an untimely fate.’Twas in the year Eighteen hundred and eighty-three,

With the people of America he did agree,

For $10,000, to swim through that yawning whirlpool;

But alas! He failed in doing so — the self-conceited fool.Captain Webb, he courted danger for the sake of worldly gain

And the thought of gaining for himself — world wide fame;

And although many people warned him not to throw his life away,

He rushed madly to his fate without the least dismay.Which clearly proves he was a mad conceited fool,

For to try to swim o’er that fearful whirlpool,

When he knew so many people had perished there,

And when the people told him so, he didn’t seem to care.Had it not been for the money that lured him on

To the mighty falls of Niagara, he never would have gone

To sacrifice his precious life in such a dangerous way;

But I hope it will be a warning to others for many a long day.On Tuesday the 24th of July, Webb arrived at the falls,

And as I view the scene in my mind’s eye, my heart it appalls

To think that any man could be such a great fool,

Without the help of God, to think to swim that great whirlpool;Whereas, if he had put his trust in God before he came there,

God would have opened his blinded eyes and told him to beware;

But being too conceited in his own strength, the devil blinded his eyes,

And all thought of God and the people’s advice he therefore did despise.But the man the forgets God, God will forget him;

Because to be too conceited in your own strength before God it is a sin;

And the devil will whisper in your ear — there’s no danger in the way,

And make you rush madly on to destruction, without the least dismay.At half-past three o’clock Webb started for the river,

Which caus’d many of the spectators with fear to shiver,

As they wondered in their hearts if he would be such a fool

As to dare to swim through that hell — whirlpool.Webb was received by the people with loud and hearty cheers;

And many a heart that day was full of doubts and fears;

A many a one present did venture to say –

“He only came here to throw his life away.”The Webb entered a boat, in waiting, and was rowed by the ferry-man;

And many of the spectators seem’d to turn pale and wan;

And when asked by the boatman how much he’d made by the channel swim,

He replied $25,000 complete every dim.Have you spent it all? Was the next question McCloy put to him,

No, answered Webb, I have yet $15,000 left, every dim;

“Then” replied McCloy, “You’d better spend it before you try this swim;”

Then the captain laugh’d heartily but didn’t answer him.When the boat arrived at point opposite the “Maid of the Mist”

The captain stripped, retaining only a pair of red drawers of the smallest grist;

And at two minutes past four o’clock Webb dived from the boat;

While the shouts and applause of the crowd on the air seem’d to float.Oh, Heaven! it must have been an awe inspiring sight,

To see him battling among that hell of waters with all his might,

And seemingly swimming with ease and great confidence;

While the spectators held their breath in suspense.At one moment he was lifted high on the crest of a wave;

But he battled most manfully his life to save;

But alas! all his struggling prov’d in vain,

Because he drown’d in that merciless whirlpool God did so ordain.He was swept into the neck of that hell — whirlpool,

And was whirl’d about in it just like a light cotton spool;

While the water fiend laughingly cried ”Ha! ha! you poor silly fool,

You have lost your life, for the sake of gain, in that hell — whirlpoolI hope the Lord will be a father to his family in their distress,

For they ought to be pitied, I really must confess;

And I hope the subscribers of the money, that lured Webb to his fate,

Will give the money to Mrs. Webb, her husband’s loss to compensate.

In the Tiffany Aching young adult series of books by Terry Pratchett the Pictsies or ‘Nac Mac Feegle’ are a race of 6 inch high beings that are more Scottish than it is probably possible to be. They have as their most feared tactic on the battlefield their Gonnagale who at times of greatest danger recites strange and terrible poetry which has the effect of reducing all that hear it to gibbering wrecks. The poems, and his title, are clearly based on the works of William McGonagall and are a tribute to the man whose writings approach genius by being so atrocious they reach round the spectrum of quality and get there from the other side.

Read him and weep

from laughter