Although Penelope Lively is nowadays best known for her books for adults, having been shortlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize three times and winning it in 1987, she started out as a children’s author and this was her fifth book. all of which had been aimed at children. The Ghost of Thomas Kempe was published in 1973 and won the Carnegie Medal, as best children’s book of the year which makes Lively the only author to win both of these major book prizes. Just for good measure she also won the Whitbread Children’s Book award in 1976 amongst other book prizes over the years.

I was prompted to pick this book up however due to an instagram post I saw last week which featured the Puffin edition and brought back happy memories of reading it all those decades ago. I knew exactly where it was on the shelves so I had to get it out and those memories haven’t let me down, it is still a fun read. The story starts with workmen renovating East End Cottage in the growing small town of Ledsham before a new family are due to move in. As one of them removes a rotten piece of wood from under the windowsill in the attic room a small bottle falls out and smashes on the floor and unbeknown to them something, or someone is released. This is the featured illustration on the title page and gives an immediate indication of the delightful drawings by Antony Maitland used to illustrate the book.

The room is destined to be the bedroom for James and at first he is very happy to have such an interesting room, all odd angles, so much better than the normal shaped rooms occupied by his sister Helen and their parents. It’s not long however before things start to very badly wrong as Thomas Kempe makes his presence felt. Kempe was a sorcerer back in the last sixteenth and early seventeenth century and had lived at East End Cottage, now he is a poltergeist and a particularly annoying one, smashing items, slamming doors, along with throwing things at James when he won’t do what he wants, because the worst thing is the notes making it quite clear that he regards James as a particularly useless apprentice and is intent on making his life as difficult as possible. Unfortunately for James he appears to be the only person who knows what is really going on, his parents are very sensible and don’t believe in ghosts so suggesting that is the real cause of the problems is a non starter. James therefore becomes blamed for the disturbances and broken items and suspected of the vandalism in the town as Kempe writes abusive messages on doors, walls and fences all over the place making clear his dislike of modern times and the people living in ‘his’ village. What is James to do?

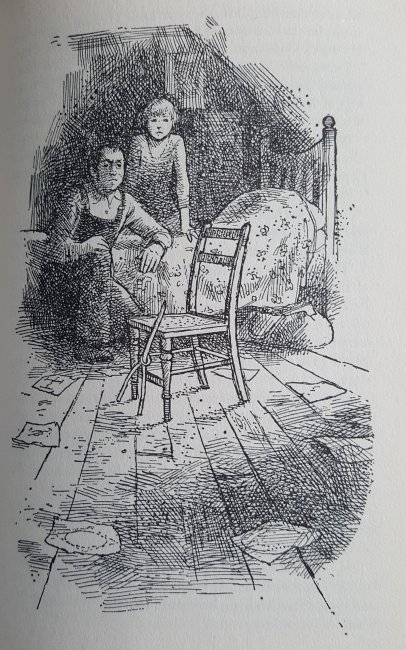

Fortunately for James he eventually meets Bert Ellison, builder and part time exorcist, and finally he has somebody who not only believes him but may be able to do something about the increasingly erratic ghost. The picture below shows Bert’s second attempt at exorcising Thomas Kempe, which unfortunately is no more successful than the first. But then again the reader knew this would fail for some reason as there is still far too much of the book to go. The story rattles along and all to soon I had finished with a satisfying conclusion. I doubt I have picked the book up, other than to transfer it from shelf to box and back to shelf over various house moves, in over forty years but it was still there when I wanted it and it’s been a very enjoyable read.

This is one of my few remaining books from the Foyles Children’s Book Club, that I was a member of from about the age of five or six up to at least twelve. I discussed the club in an earlier blog and I was either eleven or twelve when this book came out in the club edition in 1974, it doesn’t say which month so I don’t know for sure. These monthly books were really formative of my early reading and as can be seen below from the back cover of this edition they were a real bargain. You could also have books from any of the other clubs either as well, or I think instead, and it was around this time I broadened my reading by dabbling with the science and travel clubs as well before leaving the club as I discovered science fiction and would rather have the choice in my local book shop rather than a monthly book in the post. I am forever grateful to the Children’s Book Club though and I hope there is something similar still going on somewhere.