My latest limited edition book from The Folio Society is The Wanderer illustrated and signed by Alan Lee. An artist best known for his decades long association with works by Tolkien, both in illustrating his books and his many years in New Zealand working on the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies.

The text is largely from a 1966 Penguin Classic ‘The Earliest English Poems’, translated by Michael Alexander, which also included four pages of Beowulf. Over the years this has been revised until the 2008 edition which provides the entire text for this book, with some amendments, which by then was entitled ‘The First Poems in English’. Lee was approached by The Folio Society to see if he would like to illustrate something for them and between them chose this work as it takes him back to the source materials that so inspired Tolkien in his writings. This is by no means a typical way round, the society would normally choose a book that they wanted to publish and then approach an artist to illustrate it; but what it has produced is a book where you can see the love the artist has for the material and I suspect they eventually had to stop him from creating any more artwork so that the book could actually get published. As it is each poem has its own distinctive decorative borders along with the beautiful tipped in colour paintings and on page printed black and white illustrations.

The poems and riddles themselves come from a very short window in time, between the reign of King Alfred the Great over the Anglo Saxons (886 to 899AD) where he started the process of moving the written word from Latin to Old-English and the Norman invasion of 1066 when all that was swept away with the imposition of Norman French. In truth there were probably just thirty or forty years where Old-English hit its peak before becoming almost extinct. The greatest source material for the work of this period is The Exeter Book which was regarded as largely worthless for centuries before becoming recognised as the treasure trove that it is. The poems are much more powerful than might be expected from their great age, they clearly come from an oral tradition as they are directed at the reader as though being read to them, I am reminded of the Icelandic sagas in concept if not in size. Indeed as Bernard O’Donoghue writes in his especially commissioned foreword

There’s a vitality to these poems, written as they were at a time when life was so much more embattled, more desperate and fragile

Along with the general introduction and note on translation each poem has its own introduction setting the scene for the following work and providing mush needed context. The works are over a thousand years old and the people who wrote and read them were very different to ourselves.

The original Penguin book its variants and companion volumes have sold over a million copies in the fifty years since they came out and the quality of the work shows exactly why Michael Alexander is such a respected translator and this edition makes reading them so much more of a joy than the original paperbacks. The text is presented with the original on the left hand side and the translation on the right as can be seen in one of my favourite works included the fragment of ‘The Battle of Maldon’ from the section of Heroic Poems. I suspect I like these more than the somewhat more introspective other poems is my fondness for the sagas and these have more of a feel of those. However this is an account of a real battle that can be also seen in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to such a level of detail that there is also an accompanying map included with the text so the reader can easily see how the fight progresses, which frankly is not well for the English side and a lot better for the attacking Vikings.

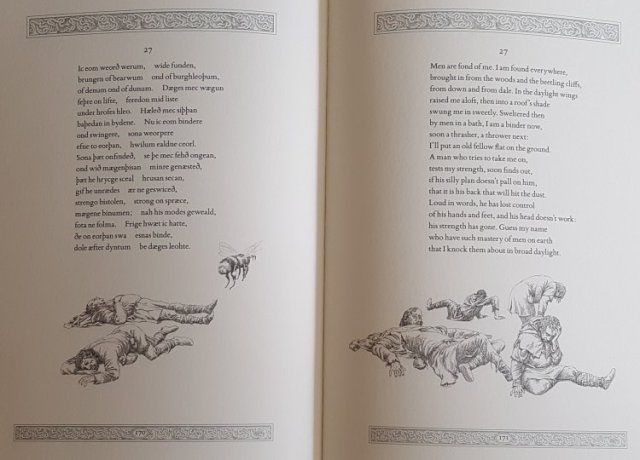

The riddles are great fun and at the back are a set of proposed solutions, however the one that I have shown as an example also has drawings by Alan Lee which somewhat give away the answer. All the riddles are from The Exeter Book where presumably there are a lot more as these start at number seven and there are lots of numeric gaps.

The answer is of course mead.

As only 750 copies were printed at £395 each and these are all sold out from the Folio Society it would be difficult to get a copy of this fine edition, but if I have whetted your appetite for Old-English poetry and riddles then the Penguin paperback is still in print and considerably cheaper.

There is a short video showing the book from the Folio Society

and a longer video of an interview with Alan Lee.