Porterhouse Blue was Tom Sharpe’s third novel and the first set in England after two mocking the apartheid regime in South Africa where he had lived from 1951 before being deported for sedition in 1961. Before going any further with the review however it is important to take note of the language used in a couple of early chapters and one later one, which can euphemistically be referred to as ‘of its time’ especially of the early 1970’s by a white person who had spent a decade in South Africa. It also probably goes some way to explaining why the book does not appear to have been in print for the best part of two decades in the UK. These three paragraphs aside the book is a fun read, with the conflicts, and other relations, between the characters driving forward the story. The opening paragraph sets the scene as the hidebound, male only, Porterhouse College with it’s tradition of big dinners, sporting prowess and low academic achievement has no idea what is about to hit it with the appointment of a new Master of College.

The new Master, Sir Godber Evans, has plans to shake up the old ways in this bastion of maleness; for a start he wants to be co-educational, start accepting students on the basis of academic qualifications rather than muscle for the rugby team and rowing crews, and horror of horrors turn the dining hall into a self service cafeteria run by outside caterers. More disastrous plans come to light, disastrous at least in the eyes of the senior faculty who quite like the big dinners, fine wines and a laissez-faire attitude to educational success that has characterised Porterhouse College for centuries. He must be stopped but how?

Another bastion of the traditions of the college is Skullion, the Head Porter, a role he has held for 45 years. It’s a job he is ideally suited for calling as it does for a total deference to ‘his betters’, i.e. the faculty, at least to their faces, a mindless application of the college rules especially where students are concerned and limited ambition. All these traits he gained in the lower ranks of the army along with fastidious attention to the shine on his shoes which he polishes daily as part of his fixed routine and which serves as a calming influence whenever he is upset. Being upset is going to be his standard position from the arrival of the new Master onwards and often with good reason. It is Skullion we follow more than any other character as the plot unfurls as he seeks to thwart the new masters plans with the help of former pupils known to himself as Skullions Scholars who he has helped pass their degrees by hiring capable students from other colleges to write essays or at the last resort sit the final exams for them.

There is another plot line, which barely touches on the main plot, and that is of Zipser, Porterhouse’s only research student, and the lustful feelings he has for Mrs Biggs his bedder, or servant who cleans and tidies his rooms in college. Mrs Biggs is a lady of mature years and large figure who not only realises Zipser’s desire but determines to reciprocate, Mr Biggs having passed away many years earlier. Zipser and Mrs Biggs storyline however reaches its climax just over halfway through the novel and only the aftermath is dealt with following that.

It’s worth pointing out the origins of the title. A Blue at Cambridge or Oxford is a person who has represented the university in a sporting event between the two universities and as Porterhouse is depicted as a sporting college then students from there would clearly be represented amongst the Cambridge Blues. But a Porterhouse Blue has another meaning as well and is down to the huge meals consumed there regularly and refers to the likely stroke that people with high blood pressure, cholesterol levels, obesity and probable diabetes brought on by such an unhealthy diet are likely to suffer from.

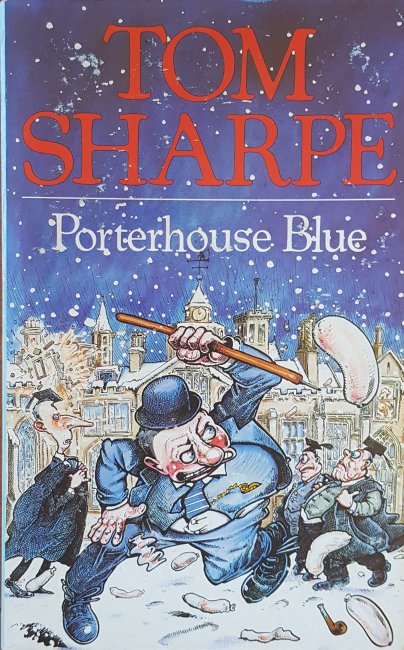

The book was adapted by Malcolm Bradbury as a four part TV series in 1986 starring David Jason as Skullion and Ian Richardson as Sir Godber Evans and that is how I first came across it. My copy is the 1976 first paperback edition with a cover illustration by Paul Sample which I bought second hand probably soon after the TV series was broadcast. The cover depicts one of the funniest scenes in the book as Skullion attempts to rid the college grounds of over 200 gas filled and highly slippery condoms in the middle of the night in a snowstorm. There is no way I’m explaining how they came to be there or the circumstances of their removal you’ll just have to read the book.