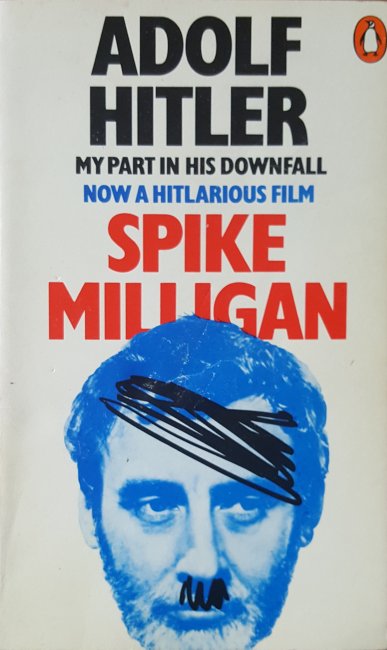

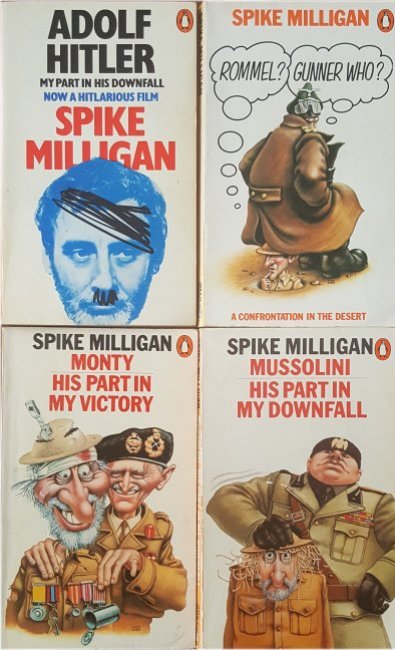

Spike Milligan’s memoirs of his time in D Battery of the 56th Heavy Artillery during World War 2 are as he says in the preface accurate “All the salient facts are true, I have garnished some of them in my own manner, but the basic facts are, as I say, true”. I would say that most of the ‘garnishing’ is down to hindsight allowing more humour to come through than was probably the case at the time. Milligan kept a diary right trough his service years and kept in touch with many of the men he served with over the following years, not just at the annual D Battery dinner which he attended regularly, but also to cross-reference his own memories. He therefore used to get very annoyed with critics who, especially in the later volumes, accused him of making things up. The preface also says that it was planned to be a trilogy although ultimately he wrote seven volumes, of which I have the first four which cover his active service and were all written in the 1970’s. The remaining books “Where Have all the Bullets Gone?” (1985), “Goodbye Soldier” (1986) and “Peace Work” (1991) deal with his time being hospitalised after being wounded at Monte Cassino through to eventually being demobbed and the early days of his career in entertainment building on his skills honed as a trumpeter and guitar player in the battery, and later the NAAFI, bands.

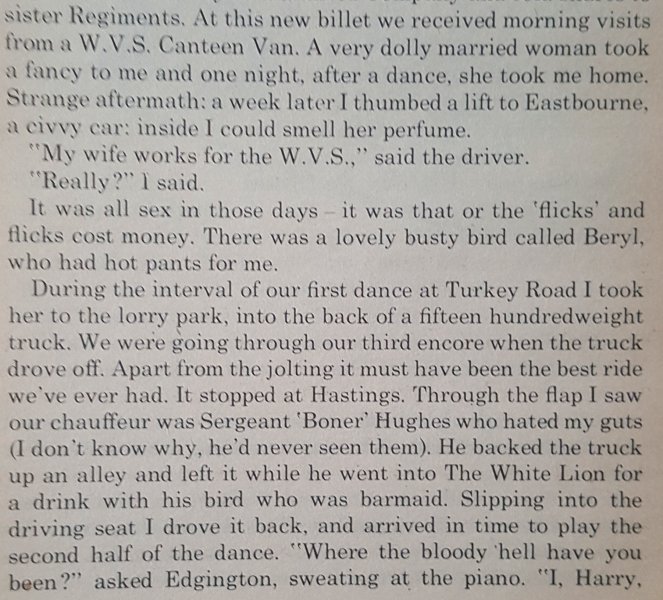

This volume deals with the events from the outbreak of war in September 1939 through joining his regiment in June 1940 to his arrival in Algiers in January 1943. As you can tell from these dates he spent a large part of the war at various camps along the south east coast of England before finally being posted to North Africa to see active service where he worked as a signaller for the battery. As you would expect from a comedy writer of Milligan’s ability the stories of his military experiences are told with humour as are his various attempts at relationships with the opposite sex, some successful others less so, never rising above the dizzy heights of lance bombardier, and that only whilst in Europe, somewhat cramped his style with the ladies whom tended to prefer the officer class if available but he does document a few successes and their aftermath, the following section covers a couple of those successes and also gives a hint as to the style of the rest of the book.

“have been having it off in the back of a lorry, and I got carried away”. He doesn’t explain how Sergeant Hughes managed to get back from Hastings, presumably he didn’t care.

There are also a lot of descriptions of the banality of life in camp and the things that were done in order to relieve the boredom all of which are highly entertaining to read about. Milligan got jankers (disciplined for breach of regulations, usually being confined to barracks and assigned various menial jobs) on more than one occasion and describes his first punishment in the book. He was attempting to get coal up to his first floor barrack room by means of a bucket on a rope with the assistance of his good friend Harry Edgington, who loaded the bucket from the stores however this was on a day when fires were not permitted when there was a surprise inspection. Spike therefore stopped hauling on the rope but Harry misinterpreting this sudden pause yanked on the rope and pulled Spike backwards out of the window which was a bit of a giveaway.

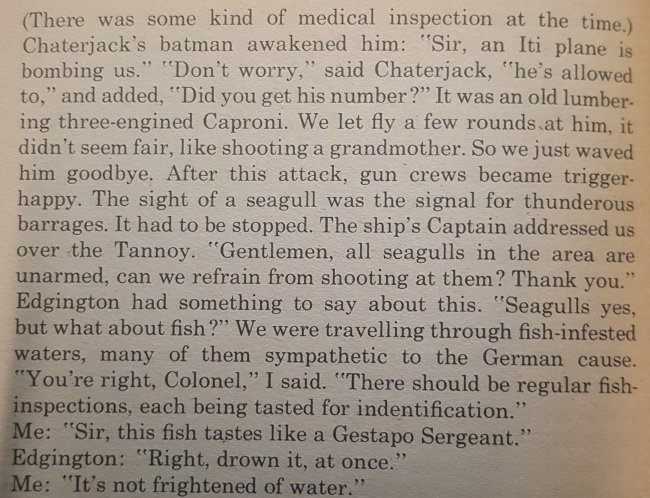

A later section, on board the troop ship approaching Algeria gives a hint of the sort of humour that would make Spike Milligan famous whilst writing The Goon Show scripts for the BBC in the 1950’s with their lunatic extensions of logic.

It has been great fun reading this memoir again and I’m now inspired to read the other three that I have. I suspect the three final post active service volumes will be quite a bit darker as they will have to deal with his ongoing problems with mental health which saw him hospitalised several times.