In 1890 naturalised Briton, although Polish born, Captain Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski left England to take command of the steamship Roi des Belges on the River Congo. He had gained his Master of the British Merchant Marine certificate four years earlier and had had a previous command of a ship called the Otago but this was to be his most significant position, at least as far as it’s mark on his later life. He had begun his maritime career back in 1875 as a trainee seaman on the barque Mont Blanc and had worked his way up the ranks on various vessels over the following years and hoped this would be a stepping stone to command of larger ships but it wasn’t to be. Amongst the possessions he took with him for an expected 3 years away in the Congo was a manuscript for a novel he was working on and it was this, along with the ill health that followed his African adventure that largely kept his away from future seagoing, would make the name of Joseph Conrad. ‘Almayer’s Folly’ was published in 1895, 15 months after he left his final marine post and a stream of novels and stories were to follow including the novella ‘Heart of Darkness’ based on his time in the Congo and published in 1899.

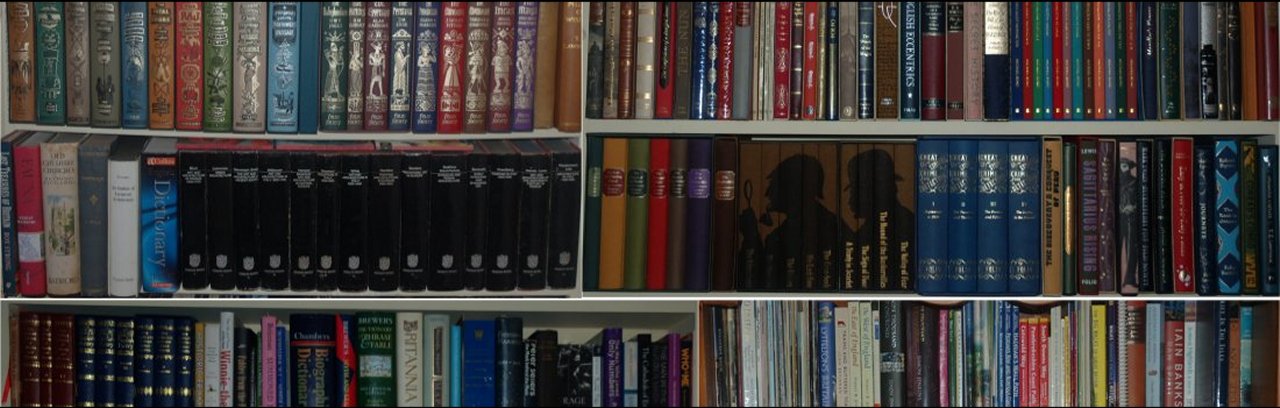

Although I will refer to Heart of Darkness several times during this essay, the book that has prompted me to write is ‘Conrad’s Congo’ published by the Folio Society in 2013 which gathers for the first time in one volume letters and diaries by Conrad relating to his ill-fated trip, along with the short story ‘An Outpost of Progress’ which also draws on his time in Congo. The book is bound in cloth blocked with a design by Neil Gower of the Roi des Belges steaming along the Congo. At 256 pages it is more than twice the length of Heart of Darkness and includes some fascinating contemporary photographs.

The Congo at the time was being run a private fiefdom by King Leopold II of Belgium and the astonishing cruelty against and exploitation of the people there was without parallel even amongst other colonies. It only started to be reigned in after the report into what was happening there by Roger Casement became public and eventually the Belgian government stripped Leopold of his autocratic control. It is estimated that of Congo’s 20 million population in 1880 this was roughly halved by 1920 mainly from famine and disease as all able bodied people were forced to work collecting ivory, rubber or other commodities to enrich Leopold meaning there was nobody to hunt, fish or plant crops. Part of Casement’s report is included as an appendix to the book and makes disturbing reading even though I already knew some of the background.

The cover of the Penguin Popular Classics edition of Heart of Darkness was chosen by somebody who wanted a dark jungle view but managed to select not only the wrong country but even the wrong continent as the painting is a detail from Hunter in Brazilian Jungle by Marrin J Heade, so the plants growing are completely wrong for Africa.

Conrad’s Congo starts off with a series of letters initially with Albert Thys, deputy director of the Belgian Company of the Upper Congo as he tries to get a job with them then moves on to letters to his distant cousin (although referred to as uncle in the letters) Aleksander Poradowski then living in Belgium and when he dies soon after this correspondence starts the letters continue to his widow Marguerite (written to as aunt) and it is she that helps get him the captaincy he is looking for. In Heart of Darkness this is fictionalised in the tale told by Marlow (a thinly disguised Conrad) in which he says

“I am sorry to own I began to worry them. This was already a fresh departure for me. I was not used to get things that way, you know. I always went my own road and on my own legs where I had a mind to go. I wouldn’t have believed it of myself; but, then–you see–I felt somehow I must get there by hook or by crook. So I worried them. The men said ‘My dear fellow,’ and did nothing. Then–would you believe it?–I tried the women. I, Charlie Marlow, set the women to work–to get a job. Heavens! Well, you see, the notion drove me. I had an aunt, a dear enthusiastic soul. She wrote: ‘It will be delightful. I am ready to do anything, anything for you. It is a glorious idea. I know the wife of a very high personage in the Administration, and also a man who has lots of influence with,’ etc. She was determined to make no end of fuss to get me appointed skipper of a river steamboat, if such was my fancy.

Six months after approaching Thys, Conrad had his job and his letters to his ‘aunt’ continue through his voyage to the Congo talking about the trip but also his first impression of colonial Africa as he works his way along to coast encountering French ships. The letters hint at a growing romantic link between the two as the tone becomes more playful such as might be written between two lovers separated by distance. On arrival at Matadi he finds that the Roi des Belges is 200 miles away and there is no way to get there up the river due to the rapids between the coast and the station where the ship awaits him so Conrad is forced to walk to his boat and this is covered in ‘The Congo Diary’ which makes up the next section of the book. It is in this short work where he meets Roger Casement and we first read of the casual cruelty inflicted on the natives and hints as to the fate of the majority of the colonialists.

On the road today passed a skeleton tied up to a post. Also white man’s grave – no name. Heap of stones in the form of a cross.

The short Congo Diary is immediately followed with ‘The Up-river book’ which covers his first trip on the Roi des Belges and is largely technical notes presumably to assist him in future trips such as this part of the entry for the 3rd August 1890.

Always keep the high mountain ahead crossing over to the left bank. To port of highest mount a low black point. Opposite a long island stretching across. The shore is wooded –

As you approach the shore the black point and the island close in together – No danger – steering close to the mainland between the island and the grassy sandbank, towards the high mount.

There are also numerous sketch maps of sections of the river which are also included in the Folio edition. The endpapers of this book have maps for both The Congo Diary and The Up-river Book so that you can follow the journeys.

Unlike in Heart of Darkness where Marlow on having walked to his boat just as Conrad did, the Roi des Belges was clearly ready to sail as they set off a couple of days after he arrived. In the story Marlow found his ship had sunk a few days earlier so was obliged to spend many months getting it out of the water and repaired before they could do anything. The enforced break affords Conrad the chance to set up his plot for the rest of the story and also to make various observations about the conditions the natives are under. In reality he was off from Kinshasa to Stanley Falls almost immediately. This section of the Folio book is frankly not very readable and in truth was not intended to be so as it is really just notes on the route to avoid the numerous sandbanks and rocky snags that litter the river. Conrad’s sketch maps are interesting with their dotted lines indicating the correct path between islands especially the long section dealing with the clearly complicated Lulanga river passage, this takes 7 maps and several pages of notes to get through so it must have had a justified reputation for difficulty in navigation.

At the end of The Up-river book we are back to a small section of correspondence as letters have caught up with Conrad at Stanley Falls. One of these is highly significant as the letter to Marguerite includes the first mention that he has been very ill with dysentery as well as fever (malaria) and that there is a mutual dislike between him and the manager of the station he is based at so there is little hope of any advancement in his career. It is quite clear from the letter that the manager of the station that Marlow finds himself at is modelled on the real Monsieur Delcommune. This is how Marlow describes him..

He was commonplace in complexion, in features, in manners, and in voice. He was of middle size and of ordinary build. His eyes, of the usual blue, were perhaps remarkably cold, and he certainly could make his glance fall on one as trenchant and heavy as an axe. But even at these times the rest of his person seemed to disclaim the intention. Otherwise there was only an indefinable, faint expression of his lips, something stealthy–a smile–not a smile–I remember it, but I can’t explain. It was unconscious, this smile was, though just after he had said something it got intensified for an instant. It came at the end of his speeches like a seal applied on the words to make the meaning of the commonest phrase appear absolutely inscrutable. He was a common trader, from his youth up employed in these parts–nothing more. He was obeyed, yet he inspired neither love nor fear, nor even respect. He inspired uneasiness. That was it! Uneasiness. Not a definite mistrust–just uneasiness–nothing more. You have no idea how effective such a… a… faculty can be. He had no genius for organizing, for initiative, or for order even. That was evident in such things as the deplorable state of the station. He had no learning, and no intelligence.

The last letter in this section is to the publisher Thomas Fisher Unwin who was acting as Conrad’s literary agent and mentions the short story ‘An Outpost of Progress’ based on his experience at the station which makes up the next section of the Folio volume.

Conrad would be invalided out of the Congo by the end of 1890 to the relief not only to himself but also to Delcommune who wanted rid of him, and never recovered his health. Malaria is one of those persistent diseases that keeps flaring back up and it would afflict him several times back in England. The remainder of the Folio book is letters he sent long after his return, including 3 to Roger Casement at the end of 1903 just before the Casement report was published in February 1904, along with extracts from articles he wrote, followed by 2 appendices. The first of these is a series of five short testaments about Conrad written by people who met him including John Galsworthy and Bertrand Russell and then finally the extracts from Casement’s report that was mentioned earlier.

All in all a fascinating book which gives an insight into the creation of Heart of Darkness and which even if you have never read the novella provides an overview of the awful situation in the Congo under Belgian control and it should be recommended if only for the historical record.