I recently watched the 1974 film Akenfield directed by Peter Hall which is based on Ronald Blythe’s best seller ‘Akenfield, Portrait of an English Village’, a book that has remained in print ever sine it was first published in 1969. The film covers three generations of people from the fictitious village of Akenfield in Suffolk including its most famous bucolic scenes of farming life that has long since disappeared and the horrors of losing so many men to the World Wars. It is particularly unusual in that there are no professional actors and no script just an eighteen page synopsis by Blythe with the people in the film making their own lines up as appropriate for the scene. The film was made at the weekends so as not to impinge on the actual working week of the people taking part and Blythe himself appears in it, playing the part of the vicar of Akenfeld, you can see the trailer here.

I loved the film and was sure that somewhere on the shelves was the book which was memorably reviewed by Jan Morris for the New York Times:

“Ronald Blythe lovingly draws apart the curtains of legend and landscape, revealing the inner, almost clandestine, spirit of the village behind. His book consists of a series of direct-speech monologues, delivered by forty-nine Suffolk residents, and interpretatively linked by the author. The effect is one of astonishing immediacy: it is as if those country people have looked up for a moment from their plow, lawnmower or kitchen sink, and are talking directly (and disturbingly frankly) to the reader. This is a brilliant and extraordinary book which raises disquieting second thoughts when the poetry has faded—as Mr. Blythe says, it is like a ‘strange journey through a familiar land.”

Sadly I couldn’t find it but I did locate the next best thing, a 126 page shortened version of the original 288 page Penguin Modern Classic from the set English Journeys which came out in 2009. This only has twenty one of the original forty nine interviews and the linking passages are largely missing but in the absence of the complete work it is an excellent substitute. The variety of people interviewed by Blythe is a cross-section of village life from a thatcher, blacksmiths and a wheelwright, a nurse, a couple of orchard workers and even one of the gardeners from the big house who describes the problems of working for the old couple that owned it and the professional pride that he got from a job well done. In fact there was a lot of pride in what people were doing right up until the younger generation and a tractor driver who no longer cared about straight furrows just how much land he could cover in a day, in total contrast to the horse ploughman who wanted everything just so.

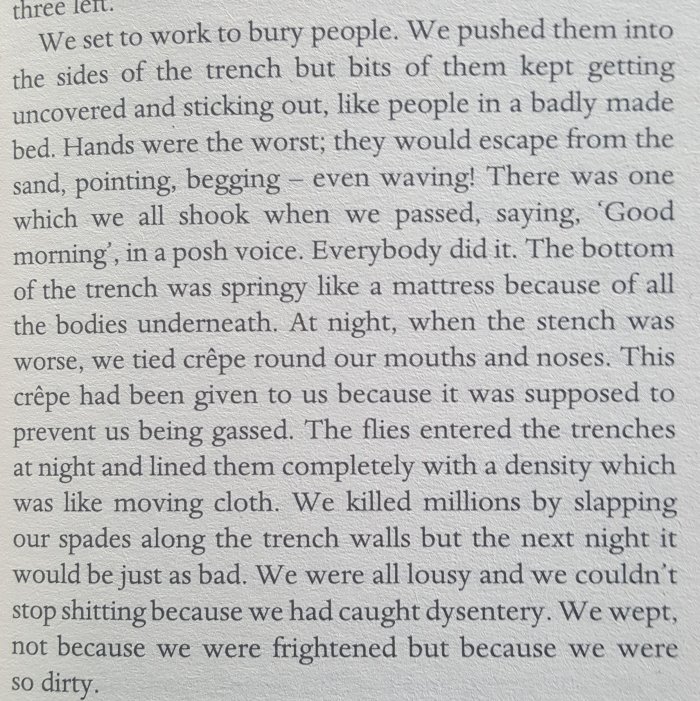

The saddest, and most difficult to read, interview was the first one in the book, Leonard Thompson age seventy one and listed as a farm worker but most of his narrative covers being called up in the First World War and having to go to The Dardanelles to fight the Turks before ending up on the Somme in the thick of the fighting. He describes first arriving in Turkey and asking about friends from the village who had gone before only to be told that they had all died in combat and then moving on to a trench which was full of corpses and stinking from the decomposition.

One of the more interesting interviews was with a saddler who admits “Our harness lasted forever, as you might say. It was our downfall, wasn’t it! We made these things so well that after a while they did us out of a living.” But even the wheelwright says that there were wagons around the village that were over a century old they were made that well that they never needed replacing. So different from modern products which have built in obsolescence, it was only the coming of tractors that would gradually drive those fine wooden wagons off the farm and into the history books. The retired district nurse describes arriving in Akenfield in 1925 and being the first medical professional that would actually turn out at a house as the local doctors weren’t interested in house calls, you had to go to them and be ready to pay or they wouldn’t see you at all. She saw it all from births to sitting up by a death bed as the person in it took their final breaths and had to work hard to gain the confidence of the people. She eventually covered nine villages and because of this was one of the few people with a car so she could get round but she was very struck by the poverty of the general population with large families in tiny properties so there would be five or six children sharing one bedroom with the latest baby in the other room with the parents.

The final person is appropriately William Russ, aged sixty one and the gravedigger. He started digging graves when he was just twelve years old, “People would look down into the hole and see a child”. One of the problems with his job was one I had never thought about and that was the high water table in Suffolk which meant that the graves would start filling up with water almost as soon a they were dug and coffins had to be held down with poles to stop them floating away until enough heavy soil was on top of them to force them down to the bottom of the grave.

All in all it’s a fascinating document of social history and I just need to keep hunting the shelves to find the full work although I have a feeling that I lent it to someone and never got it back. But I recommend either edition of Akenfield, or even the film, if you want a glimpse of a rural life that wasn’t that long ago but has now completely vanished.