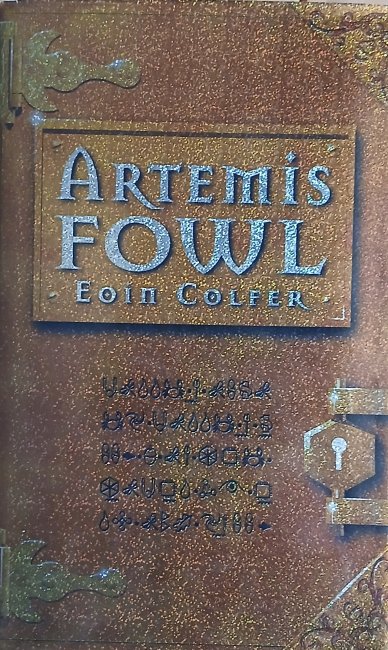

This is the first of an eleven book series written by Irish author Eoin Colfer, eight of which are about Artemis Fowl II and in the final three books, which are effectively a reboot, his twin younger brothers. My copy is a hardback from the first year of publication, 2001, and has a metallic, highly reflective dust jacket which made it very difficult to photograph. Later editions retain the gold colouring but are not metallic. At the start of this book is an introductory prologue which finishes as follows:

Artemis Fowl had devised a plan to restore his family’s fortune. A plan that could topple civilisations and plunge the planet into a cross-species war.

He was twelve years old at the time…

This last line, more than anything else in the prologue, establishes that we are in the literary genre known as young adult, which is not a area I have explored on this blog for a while so please be aware that this book is not aimed at me as a typical reader. Having said that I quite enjoyed this, and the next two books which I have also read, I have also discussed the series with other people who first read the books whilst they were within the target age range of roughly twelve to eighteen to obtain a more rounded viewpoint.

Artemis’s father is missing, presumed dead and his mother has become a barely functioning recluse in the attic triggered by her grief for her missing husband, this leaves Artemis without parental supervision in his parents large house in Ireland with only his mountainous bodyguard, deliberately confusingly called Butler and Butler’s younger sister Juliet. There are presumably servants but they don’t appear in the narrative. The family money was built upon criminal enterprises and Artemis is definitely a chip off the old block but he believes he has found a target for his genius beyond the jurisdiction of the Irish Gardaí or indeed any normal police force, his plan is to get money from the fairy world by obtaining their legendary supply of gold. And so we are entering the realm of fairies, elves, dwarfs, trolls and other magical creatures but not as imagined by Tolkein, Pratchett or others who have raided mythology for their characters modifying them to suit their plots. Here the changes are if anything more radical, dwarfs chew their way through the earth having first dislocated their jaws and expelling the residue via what can most delicately be called their opposite end having first dropped the flap in their trousers. That Butler at one point is in the way of a cataclysmic fart from Mulch Diggums. the kleptomaniac dwarf, is clearly there to appeal to the younger readers who by and large can never resist a fart joke. Elves are approximately a meter tall and one of the books major characters, Holly Short, is one of those, she is also part of LEPrecon, part of the police force for the fairy peoples who are now forced to live deep underground to avoid the Mud People as they refer to humans. Colfer explains that LEP stands for Lower Elements Police a somewhat tenuous forcing of the word Leprechaun into his plot line.

I’m not going to go into the plot of the book, suffice to say that Artemis has quite an ingenious plan to part the fairies from their gold which first involves deciphering their language, a sample of which is on the cover and which is also depicted on the base of each page of the novel, as far as I can tell differently on each page. The story moves on at quite a pace and I found myself at the end of the 280 pages far quicker than I expected. I mentioned at the beginning that I have read the first three Artemis Fowl books and talking to my friends who read them as teenagers I’m told I shouldn’t go much beyond about book five as they reckon that the plots get a bit similar as though Colfer was running out of stories to tell with these characters. One friend has read the first of the Artemis twins books but didn’t feel the urge to read the others, which I think says a lot, so by all means have a go at the early books as a bit of light reading between more weighty tomes but probably skip the later ones.