Last weeks blog about Lawrence Durrell’s book ‘Bitter Lemons of Cyprus‘ was intended to be my last encounter with the Durrell siblings for a while having started with Gerald a couple of weeks ago, but here we go again with a memoir by their sister Margaret. This deals with her time starting a lodging house in Bournemouth just over the road from the home then belonging to her mother but which was sold soon after Margo got her business running. Quite when the book was written isn’t clear but it deals with the end of the 1940’s so coincides with Gerald’s ‘The Overloaded Ark‘ which I wrote about in the first of these linked blogs. ‘Whatever Happened to Margo?’ however wasn’t published until 1995, long after Gerald’s Corfu trilogy about his childhood on that island made the family household names and gave rise to the title as whatever happened to Margo, and presumably her other brother Leslie, became regular questions amongst readers. Margaret’s book also answers some of the questions about Leslie as he appears fairly regularly in here, as at the time he is also living in Bournemouth having returned to the family fold from a business failure when the fishing boat he had put his life savings and his share of his father’s inheritance into had sunk. But more of Leslie, just to round out the family, later.

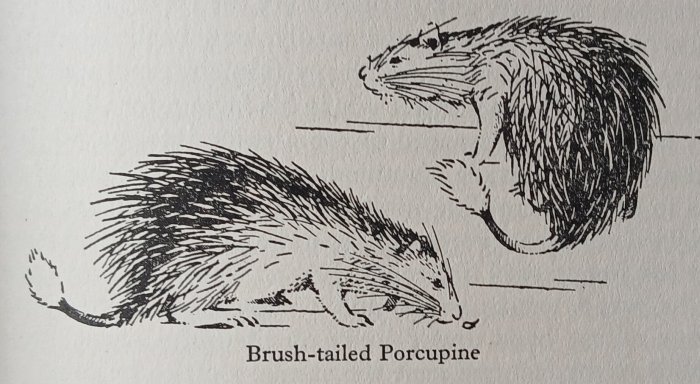

Margaret has a writing style far closer to Gerald than Lawrence with a gentle humour enveloping the trials and tribulations of running a lodging house with no previous experience of doing such a thing, especially as a young (she was twenty eight when she bought the property) recently divorced mother of two boys. We are introduced to another member of the family, Aunt Patience, early on in the book and she encourages Margaret in her business plan whilst making regular suggestions as to how to keep the place running efficiently and with propriety. Margaret is somewhat subdued by her aunts overbearing personality and also by the need to keep her sweet as the potential source of investment funds but dreads her arriving to see the somewhat eclectic mix of people she has already had moving in. Margaret attracts oddballs the way her younger brother attracts unusual animals, her first lodger is Edward, an artist who has fallen out with his previous landlady over his liking to paint nudes, along with his wife who also poses for him. She also gains the downtrodden Mrs Williams and her fat son Nelson who would prove to be a lovable rogue; always getting into scrapes, he features in numerous tales often leading Margaret’s own children in ways she would never have thought of including breeding mice in the disused outside toilet. The lodgers increase rapidly including a pair of glamorous nurses whose trail of ardent male admirers gave rise to the suggestion in the neighbourhood that Margaret was in fact running a house of ill repute. The list of interesting characters just keeps going and keeping the peace between them whilst not upsetting the neighbours is a constant battle especially when Gerald arrives with a selection of animals whilst still looking for somewhere to set up his own zoo. The book is great fun, and whilst not a laugh out loud read keeps the reader thoroughly entertained throughout its just over 250 pages.

And so to Leslie, during the time this book covers he moved in with Doris, the landlady of a local off-licence for whom he was delivering beer, they married in 1952 and later that year moved to Kenya to run a farm. They swiftly left Kenya in 1968 after Leslie was accused of theft, probably accurately as he always sailed close to the wind as far as the law was concerned, this is implied right at the start of Margaret’s book. They briefly moved in with Margaret in Bournemouth before getting a job as caretakers to a block of flats in London and it was in London that he died. By this time he had so estranged relations with the rest of the family that none of his siblings attended his funeral.

Margaret would outlive all her brothers by quite a long way. Leslie had a heart attack in 1982 aged 65, Lawrence died after a stroke in 1990 aged 78, Gerald succumbed to septicaemia in 1995 aged 70 but Margo was 87 when she died in 2007. This meant that none of her siblings saw her book get published, Gerald died in January of the year the book came out but he did write the preface in November 1994 where he states that she is still in Bournemouth, although presumably no longer a landlady as she was 75 by then. He continues that he often visits her there, just as she comes out to his zoo in Jersey and home in Provence, they have even holidayed together in Corfu so bringing the whole saga full circle. I’ll leave the final word to Gerry (as he is called in his books about Corfu) :

From the beginning and every bit as keenly as the Durrell brothers, Margo displayed an appreciation of the comic side of life and an ability to observe the foibles of people and places. Like us, she is sometimes prone to exaggeration and flights of fancy, but I think this is no bad thing when it comes to telling one’s stories in an entertaining way.