There is one name that comes to mind immediately when you think of New Years Eve and that is Robert Burns due to the international fame of Auld Lang Syne (Old Long Since) a song about a couple of friends enjoying a drink and reminiscing about things they have done in the past. But there is a lot more to Burns than a song that most people know the first verse and chorus to, even if they don’t know any more or what it means and this edition of The Penguin Poets from 1946 is a great introduction. The collection consists of forty three poems and fifty six songs and helpfully for those of us that struggle with the Scots language and dialect there is a single page glossary of common words and translations of lots of others alongside the lines where they occur.

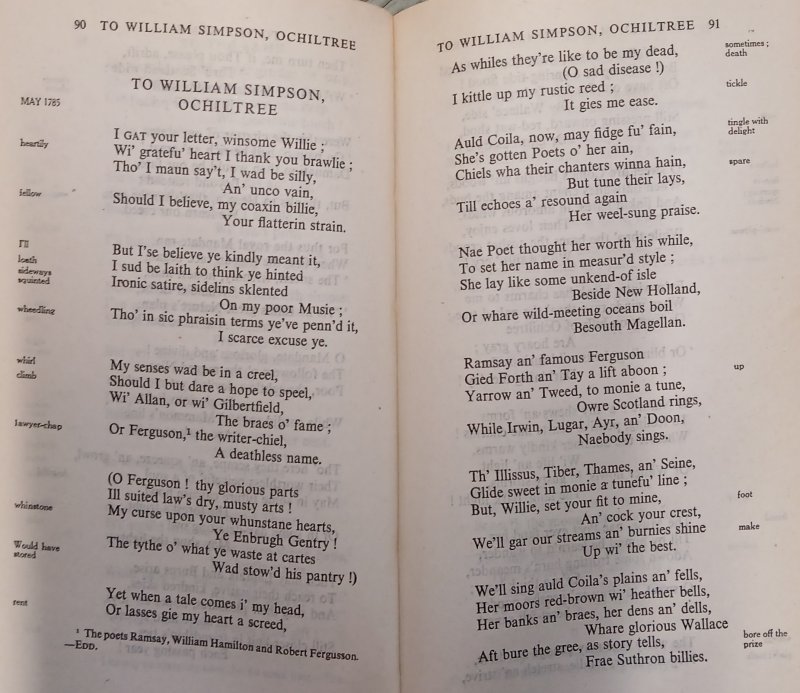

I first came across Burns at school where he was introduced as one of the pioneers of the romantic movement in poetry although we didn’t do much more than the really famous ones including, ‘To a Mouse’, ‘To a Haggis’, ‘A Red, Red Rose’ and the comedic rage expressed in ‘To a Louse’ where Burns gets so annoyed when he sees a louse on a lady’s bonnet in church, all of which are of course in this collection. I really fell in love with the musicality of Burns’ verse however when I was lucky enough to be at The Scotch Malt Whisky Society in Edinburgh for Burns Night and to hear the poems recited with the correct accent made for a wonderful evening which of course included ‘To a Haggis’ and the appropriate, for the venue, ‘Scotch Drink’, the first verse of which (after the initial quote from Solomon’s Proverbs) goes as follows…

Let other Poets raise a fracas

‘Bout vines, an’ wines, an’ drucken Bacchus,

An’ crabbit names an’ stories wrack us,

An’ grate our lug:

I sing the juice Scotch bear can mak us,

In glass or jug.

Scotch bear is barley and Burns is of course talking about whisky, the full twenty one verses of the poem can be read here, let no-one say that Burns wasn’t keen to celebrate his national drink. When I first started to read this book for this blog I did have some problems with the unfamiliar Scots dialect but as I progressed through the works I gradually found it easier to understand and found I needed to refer back to the glossary less and less. Interestingly when I have heard Burns recited I have often had far fewer issues with understanding, I guess this is similar to the way I find reading Middle English easier if I read it aloud and it then seems to make more sense than just reading silently.

So let’s finish where we started with Auld Lang Syne. This is the original version from 1788, in 1795 he changed the first line of the chorus to ‘For auld lang syne, my dear’

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And auld lang syne?(Chorus)

For auld lang syne, my jo,

For auld lang syne,

We’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.And surely ye’ll be your pint-stowp!

And surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.We twa hae run about the braes

And pu’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary foot

Sin auld lang syne.We twa hae paidl’d i’ the burn,

Frae mornin’ sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d

Sin auld lang syne.And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere!

And gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak a right guid willy waught,

For auld lang syne.

Happy new year