The book is set sometime in the 22nd century, we know this as the year 2095 is mentioned as occurring in the past. Earth has been involved in a terrible war which has led to massive depopulation to between one and two million people over the entire globe, and due to radiation poisoning a significant reduction in fertility of the survivors. The planet is now administered by the Vugs, a race of telepathic beings from Saturn’s largest moon Titan who ended the conflict and whilst not seen as occupiers of Earth they are always around. Amongst the survivors are the maybe a couple of hundred thousand Bindmen, owners of huge swathes of cities and states and their non-B residents. The Bindmen play The Game putting title deeds to their properties and even their wives as stakes in the game which is encouraged by the Vugs who both love gambling and recognise that constant swapping of partners enhances the chances of a fertile couple meeting. The story starts with Pete Garden loosing not only his favourite property, the city of Berkeley in California, but also his wife Freya and to top it off has failed to throw a three which would allow him to take another wife. To make things more on edge Pete is already a drug addict and known suicide risk having attempted to take his own life on four previous occasions.

When Pete recovers from his latest low after losing the game he visits the winner and asks to buy back Berkeley only to find it has already been traded to an American East coast player called Jerome Luckman, a man who having won most of that side of the country was looking for a way in to play on the west coast and Berkeley was to be his opening stake. Pete meanwhile moves to another of his properties where he meets a telepathic non-B female resident who has been surprisingly lucky and has three offspring and he hopes to seduce her or possibly her prettier eighteen year old daughter. That evening though Pete throws a three and is immediately married to another partner just before Luckman arrives to play the game with Pretty Blue Fox as the game group in California is known and wins so consolidating his position.

But then there is a murder and The Game is going to completely change with everything you know, or think you know drastically altered…

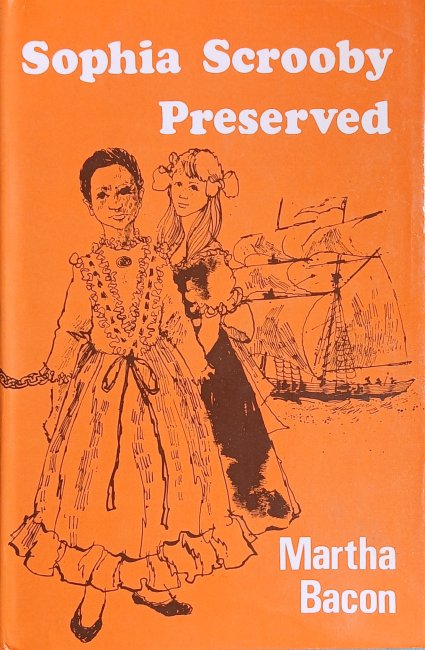

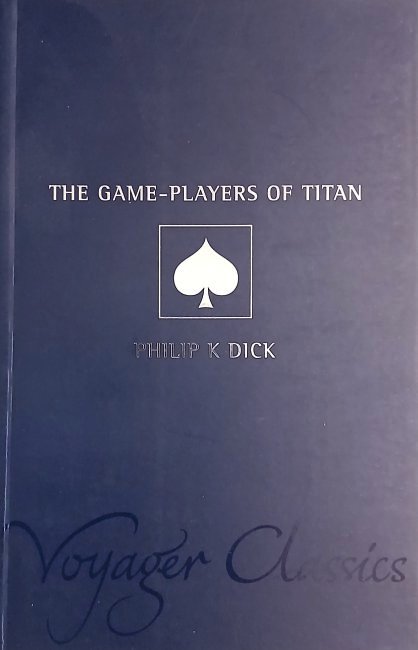

Voyager Classics was a relatively short lived series of science fiction and fantasy books from Harper Collins all with the same blue and silver cover design, with French flaps and a different small, but sort of appropriate, image in the box on the front along with the spine. In this case the ace of spades even though the game they play in the book, Bluff, is clearly a board game. At the time of writing Harper Collins still list two titles in this series on their website, however only one of these has this rather attractive cover design. The Game-Players of Titan is book ten of the thirty six listed titles at the start of the book and they must have all been released, or at least announced, simultaneously in 2001 as this is the first edition. The initial set includes the three Lord of the Rings novels along with The Silmarillion making Tolkien the most represented author, but Ray Bradbury, Stephen Donaldson, David Eddings and Kim Stanley Robinson each appear three times. Philip K Dick has one other titles in the first thirty six, ‘Counter-Clock World’.

As you can see from the title image the cover is rather glossy and difficult to photograph so I did a search on Google to see if I could find another image of the Voyager Classics edition. I did, but the title is subtly different, missing the ‘The’ and also the hyphen in Game-Players. I have no idea if this is a later erroneous edition or what but it is an interesting oddity.