Although the author is probably rarely read nowadays, this novel by Susan Ertz is still in print although I think only by Zinc Read, a publishing house that specialises in printing books that would otherwise be no longer available. Other than that example I can’t find any other books by Ertz that are still in print, which is a pity as I have enjoyed this quite charming novel, I do have a copy of her book ‘Now East, Now West’ and will definitely look for others. Madame Claire is the eighty year old widowed matriarch of three children and three adult grandchildren, all from her eldest daughter Millicent. Her two other children are Eric, the eldest, now a prominent Member of Parliament and unhappily married to Louise, and Constance who is referred to as Connie throughout the book and is definitely the black sheep of the family having run off with a Russian concert pianist and then being abandoned by him. Millicent is married to John who is a well to do barrister and their three children are Gordon who is dating Helen, the daughter of Lord Ottway, Noel, currently unemployed due to losing an arm during WWI and Judy who doesn’t really know what she wants to do but feels trapped into the cycle of marrying well and settling down which frankly she doesn’t want to do. It took me a couple of chapters to get everyone sorted out in my head along with Stephen de Lisle, ex Home Secretary who was deeply in love with Claire, so much so that he asked her to marry him a couple of decades ago when her husband Richard died. Refused he took off for the continent and hasn’t been heard from since. However the book starts with Claire receiving a letter from Stephen…

That letter from Stephen was the first of many in the book and I like this way of pushing the story forward, Ertz uses them for exposition of the various relationships which would otherwise involve many more pages of scene setting and dialogue, instead she can simply have one character explain things to another in their letters. There is no doubt that Claire runs the family but without obvious interventions, rather she suggests options that help push things along such as getting Judy sent to Cannes ostensibly to see how Stephen was recovering from his minor stroke which was stopping his return to London and the resumption of a sadly extended break in relations with Claire. Yes this was partly the reason but Claire also recognised that Judy needed a break from the suffocating situation at her family home to think through what she was going to do regarding Major Crosby aka Chip whom she had fallen for after the car she has a passenger in had hit him crossing a foggy road. Unfortunately Chip had no money, wasn’t from a ‘known family’ and didn’t have a job so Judy’s parents didn’t regard him as marriage material for their daughter, Claire however liked him so was keen to help. Beyond Madame Claire Noel is the most interactive of the other characters, always willing to help his sister and most like Claire in his ability to make the best of a situation such as being able to deal with Connie when she re-appears, again at the instigation of Claire.

The various interactions between the assorted characters are well done and whilst Ertz does go a little flowery with her prose occasionally that is probably more to do with a hundred year old writing style than any real issue with the book, which to my surprise I have greatly enjoyed. I am usually wary of works by authors who have vanished to the degree that Susan Ertz has but I think she is greatly in need of a rehabilitation of her literary reputation and I’m surprised that Persephone Books hasn’t reprinted her works as I think she would fit well with their house style.

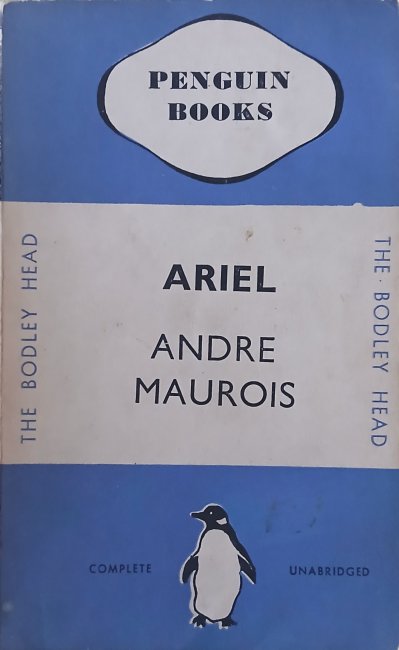

As can be seen from the full list below with their original UK publishers and publishing years, the first ten Penguin Books were an eclectic mix of titles and whilst several authors are still well known and widely read today a few have largely fallen by the wayside. They had mainly first come out in hard back in the previous decade so were very much current material in 1935 and Penguin was for the most part their first appearance in paper back. After the first printing dates I have added a number in brackets which gives the number of UK printings each book had had before being printed by Penguin, as you can see most of these books were very much in demand. The relatively low reprint numbers for the two crime novels are probably more due to the larger numbers printed for each edition for these than other genres.

- Maurois – Ariel – The Bodley Head Ltd. – 1924 (8)

- Hemingway – A Farewell to Arms – Jonathan Cape Ltd. – 1929 (9)

- Linklater – Poet’s Pub – Jonathan Cape Ltd. – 1929 (10)

- Ertz – Madame Claire – Ernest Benn Ltd. – 1923 (14)

- Sayers – The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club – Victor Gollancz Ltd. – 1928 (3)

- Christie – The Mysterious Affair at Styles – John Lane The Bodley Head Ltd. – 1920 (6)

- Nichols – Twenty-five – Jonathan Cape Ltd. – 1926 (3)

- Young – William – Jonathan Cape Ltd. – 1925 (2)

- Webb – Gone to Earth – Constable and Co. – 1917 (21)

- Mackenzie – Carnival – Macdonald and Co. – 1912 (11)

I’ve enjoyed reading the first four Penguin books over the last few weeks, and more books from the original ten will be featured on this blog over the coming months with the aim to have read them all by July 2026 so within their ninetieth birthday year. By the end of their first year Penguin had published fifty titles but were still an imprint of The Bodley Head and would not be a separate business until the beginning of 1937.