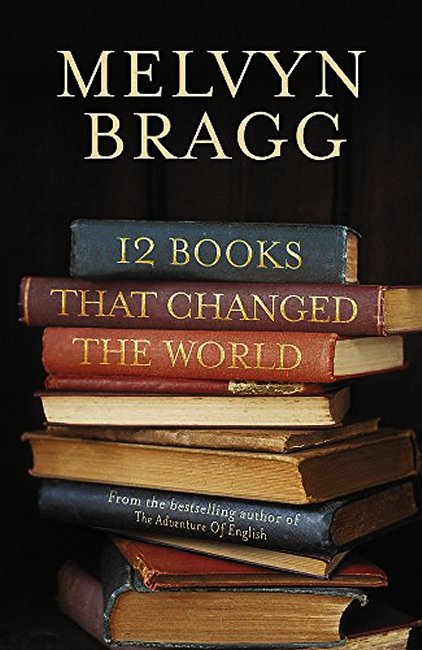

This is the 400th post on my blog so I have chosen this book to mark the occasion. It was written to accompany the 2006 ITV television series of the same name that was presented by Bragg and consisted of twelve hour long episodes looking at each work in depth, I have the first edition of the book published by Hodder and Stoughton also in 2006 but I do feel that Bragg cheated a little as he admits in the introduction.

From the beginning I wanted to enjoy a range. Leisure and literature would, if I could make it work, figure alongside science and the constitution; changes in society as well as changes in technology would be addressed. This has meant taking a risk and, now and then, elasticating the strict meaning of the word ‘book’.

Bragg certainly stretched the definition as can be seen from the list of books and documents he chose:

- Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton – 1687

- Married Love by Marie Stopes – 1918

- Magna Carta – 1213

- The Rule Book of Association Football by a group of former English Public School men – 1863

- The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin – 1859

- On the Abolition of the Slave Trade by William Wilberforce – 1789

- A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft – 1792

- Experimental Researches in Electricity by Michael Faraday – 1839, 1844 & 1855 (3 volumes)

- Patent Specification for Arkwright’s Spinning Machine by Richard Arkwright – 1769

- The King James Bible by William Tyndale and others – 1611

- An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith – 1776

- First Folio by William Shakespeare – 1623

Of these Magna Carta is definitely not a book but I can see why he included it as eight hundred years later parts of this remarkable document are still in place in the legal systems of not just the UK but America and large parts of the British Commonwealth. The Rule Book of Association Football is also barely a book, more of a pamphlet, as there are just thirteen rules and these would comfortably fit on a sheet of A4 paper. There is presumably a quantity of text surrounding these few bare lines but that isn’t made clear in Bragg’s write up. I enjoyed this choice immensely though, even though I have little interest in football, mainly for the history of the game and how the rules came to be codified combining the various versions that existed at the different public schools where the game was mainly played. I would particularly like the re-introduction of rule three which states that the the teams should change ends after each goal rather than at half time, what do football fans think of this idea? The third ‘book’ that isn’t really a book is Arkwright’s patent as it is just three pages long and as Arkwright wasn’t the actual inventor just the man who got the patent passed and then made millions (in today’s money) from other peoples ingenuity I struggle with it’s inclusion here amongst writers who did genuinely change the world.

Beyond those niggles, apart from Arkwright and the Marie Stopes book, which I must admit I have never read and therefore hadn’t thought of as a ground breaking publication, these are works I could have largely come up with myself if asked to list 12 Books that Changed the World. although like Bragg I would probably have listed far more and then had to trim the list. I think Bragg makes a good case for ‘Married Love’ though, but far less for the intellectual property theft embodied in Arkwright, you can sort of admire him as one of the first major industrialists, although his working conditions were horrific by today’s standards, but definitely not for the patent which he used to gain a monopoly for years.

But let’s look at the books that stand out in this list initially examining how Bragg has presented each one. You get a well thought out essay stating not only his case for the books’ consideration but also the history as to how it came to be written, it’s reception at the time, and the impact of the work from then until now. This is followed by a two or three page timeline of major events up to the present day associated with the ideas within the book. As an example Principia Mathematica, in which Newton not only sets out major advances in mathematics but also in the first volume created calculus and what it could do and how to do it. The book is intended for the intellectual elite of the time and as implied by the title is written in Latin so that it could be read around Europe as anyone sufficiently educated to follow what Newton was writing about could read Latin, it wasn’t translated into English until 1729, two years after Newton died. We get a summary as to how Newton worked pretty well in isolation from others and the slow appreciation that Principia had when it was published, largely due to its subject matter rather than the way it was written which was excellent for such a massive leap in mathematical study. Bragg then looks at how the modern wolrd depends on Newtons three laws of motion and the powerful mathematical tools that he defined in Principia. Then the timeline includes such momentous events as the discovery of infrared and ultraviolet light although these are more related to Newtons work on optics published in 1704 rather than the Newtonian physics of Principia.

As I write this Melvyn Bragg is still very much writing and broadcasting at the age of eighty five and is a member of the Upper House of Parliament, The House of Lords, where he sits as a Labour peer. Until he retired from the show at the beginning of September 2025 his regular broadcasting slot was the excellent radio show and podcast In Our Time which he had presented since 1998, The show picks a wildly different subject each week and discusses it with a panel of experts, it is currently on its summer break and due to start again on 18th September 2025 with a new presenter, there are over a thousand episodes available online.

400th post, that’s amazing and what an interesting book to celebrate, I love Melvyn Bragg and In Our Time. I’m interested (and pleased) that there’s no religion!

LikeLike