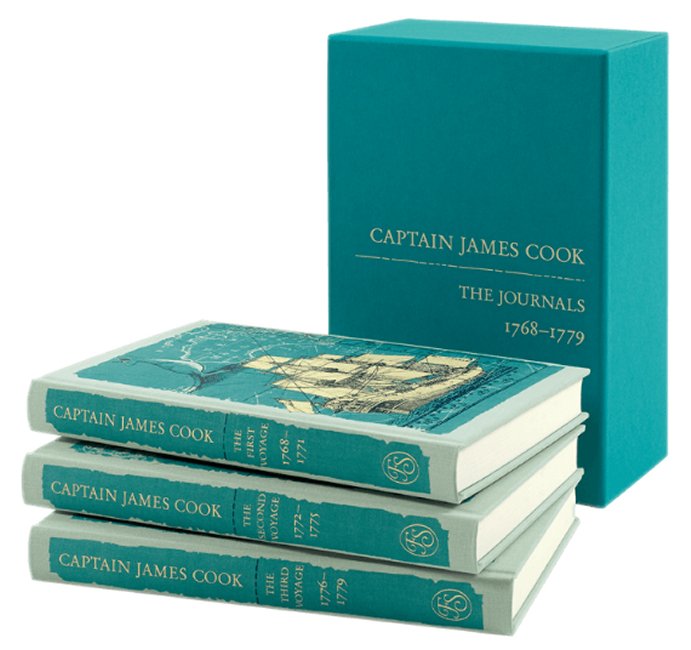

August is the month I read a theme and this year I have decided to tackle the journals written by James Cook describing his various voyages round the world. To do this I am starting off with the excellent abridged collection published by The Folio Society which is based on the JC Beaglehole version first published by The Hakluyt Society between 1955 and 1967. Beaglehole went back to Cook’s original manuscripts and ships logs and especially for the first voyage removed a lot of the extraneous material added by the Admiralty’s appointed editor which so annoyed Cook when he first saw the published work when he returned from his second voyage.

The barque HMS Endeavour set sail in August 1768 with 94 people aboard on what would be an almost three year voyage of exploration, both geographic and scientific as amongst the ships passengers were the eminent naturalist and Fellow of the Royal Society, Joseph Banks, and astronomer Charles Green specifically there to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti. There were also other scientists to assist in the collection of specimens and a couple of artists, Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan, sadly neither of which survived the trip. First port of call after leaving England was the island of Madeira for further provisions and where amongst other things they took on 3,032 gallons of wine (presumably the local fortified variety), twenty pounds of onions per man, 270 pounds of beef and amazingly a live bullock. I dread to think how killing the beast and its subsequent butchery were accomplished whilst crossing the Atlantic to Brazil on a crowded ship which was less than 100 feet (30 metres) long.

The first target destination was Tahiti for the observation of the transit of Venus due on Saturday 3rd June 1769 this was, as far as the Royal Society was concerned, the primary reason for the voyage because from this observation along with ones made in England and seven other locations around the Earth, it would be possible to accurately calculate for the first time the distance from the Earth to the Sun. Tahiti was chosen as one of the main points due to its distance from Europe, being the other side of the world therefore improved the accuracy of the calculation. By the time all the calculations were done the value was 93,726,900 miles, the modern value is 92,955,000 miles so remarkably close and within the variation of distance due to the fact the Earth does not orbit the Sun in a circle. Cook and his crew spent three months in Tahiti establishing a fortified base to make the observations from, this was necessary due to large amount of thefts that occurred from the natives who seemed to take things regardless of whether they were any use to them.

Leaving Tahiti the expedition was to search for the the legendary southern continent, but what they instead encountered was New Zealand, which had already been discovered by Abel Tasman the Dutch explorer. However over the next six months Cook would circumnavigate both the North and South Islands establishing that they were islands and mapping the coasts of them for the first time. Cook’s encounters with the Maori were fraught with disaster from the start with numerous native people being killed as they were deemed to pose a threat to either the ship or crew that landed in search of water, wood and fresh food. It is worth saying at this point that the quite small ship had by this time also taken on board some sheep as there are numerous mentions of grass being cut to feed them so it was not just the crew that needed sustenance. Cook’s interactions with the Maori people also seem to improve over the months there and there are far fewer documented fatal encounters beyond the initial landings.

After New Zealand Cook held a meeting to determine where they should go next and it was decided to sail west still looking for the southern continent. After sixteen days at sea they arrived at Australia, then called New Holland, and sailed up the north east coast of New South Wales and it is from Botany Bay that the animals shown in the plates above were seen. However whilst travelling up the coast disaster struck when on the 11th June 1770 the ship struck the Great Barrier Reef, which in this part of Australia comes very close to the shore, and was holed. After a few days they managed to get loose from the coral by dumping 40 or 50 tonnes of stores and the larger guns overboard. There then follows an interesting passage of around a month where Cook managed to beach the ship so that repairs could be undertaken and at least the large hole was repaired but the sheathing to protect the timbers was irreparable they also had considerable difficulty refloating the ship and getting back out of the trap they had found themselves in as the winds were against attempts to sail back south. Whilst trying to free themselves from a stretch of water deemed ‘The Labyrinth’ by Cook they finally managed, on 14th July 1770, to shoot one of the strange creatures spotted several times at a distance and therefore unidentifiable to find a odd animal.

The head, neck and shoulders was very small in proportion to the other parts; the tail was nearly as long as the body, thick near the rump and tapering towards the end; the fore legs were 8 inch long and the hind 22, its progression is by hopping or jumping 7 or 8 feet at each hop upon its hind legs only, for in this it makes no use of the fore, which seem to be only design’d for scratching in the ground etc. Its skin is cover’d with a short hairy fur of a dark mouse or grey colour. Excepting the head and ears which I thought was something like a hare’s it bears no sort of resemblance to any European animal I ever saw.

The entry for the 15th July includes the following observation “Today we din’d of the animal shott yesterday & thought it was excellent food”. So ended the first kangaroo examined by Europeans. The odd spelling is by the way directly from Cook’s journal, although a great seaman he was not highly educated and the spelling throughout the books is eccentric to say the least.

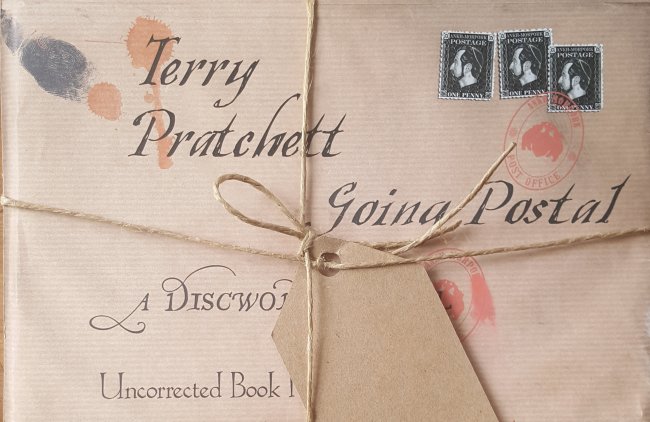

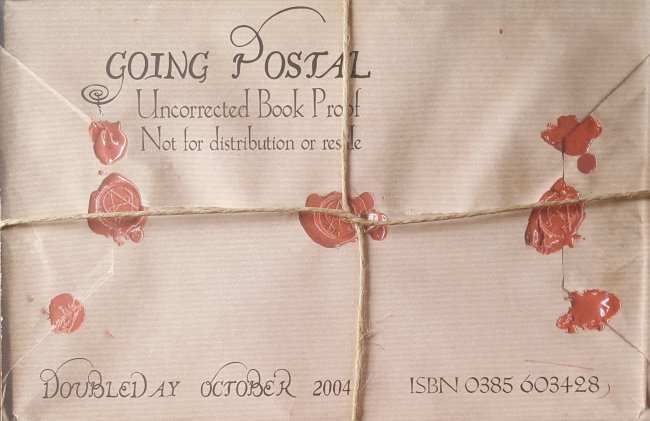

Above can be seen the Folio Society boxed set of the three voyages I am reading this month, I have the second printing from 2002.