An absolutely fascinating read, Kathryn Harkup is has a doctorate in chemistry and for six years ran an outreach program for the University of Surrey producing work on science that would “appeal to bored teenagers”. This skill set is admirably suited to explaining the chemistry in a technical, yet easy to understand way when approaching the various poisons utilised by Christie in her novels. What I hadn’t known before reading this book is that Christie was herself a dispensing chemist in a hospital up until the publication of her third book in the early 1920’s and returned to this role during WWII after retraining to update her knowledge of the various substances to be found in a hospital pharmacy. It is this background that allowed her to accurately describe not only the poisons themselves but the dosages needed and the symptoms when taken in excess and Harkup notes that she was by and large very accurate with the few errors being largely down to lack of knowledge at the time especially of the more unusual substances.

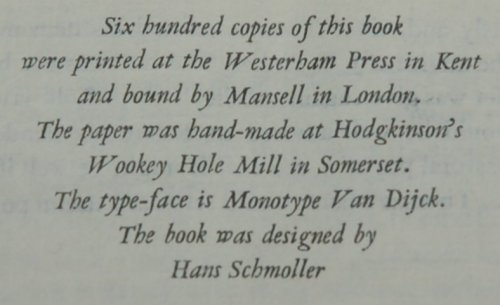

The book concludes with a couple of appendices, the first is a list of each of Christie’s novels with both UK and American titles, it’s amazing how many were changed, and the method of how each victim was killed or was attempted to be killed. For example with Christie’s own favourite book ‘The Murder of Roger Ackroyd’ we have Arsenic, Veronal *, Stabbed. The asterisk indicates that this was suicide there is also ** for attempted murder, *** for medication withheld and **** for an invented poison of which there is just one example ‘Calmo’ in ‘The Mirror Crack’d From Side to Side’. This appendix in itself is a massive piece of work, whist the second appendix gives the chemical structure of he various products referred to in the book. There is also a bibliography and a comprehensive index which underlines the scientific background of the author. Veronal by the way is one of the chemicals with its own chapter in the book and is a barbiturate and the structure of this chapter, which is mirrored by the thirteen others, will give you an idea of the thoroughness Harkup has approached her task:

Firstly we get some historical context which in this case points out that the use of barbiturates dates the books with them in as they were commonly used for suicides in the 1920’s and 30’s but have unpredictable dosages, a large amount can be survived but small doses can kill depending on various factors which cannot be accurately determined in advance. The second section looks at a real life example of the poison being used and how this may have provided a basis for Christie and compares that to the chosen book to represent the use. In this example the book chosen is ‘Lord Edgeware Dies’, which is one of several stories to have barbiturates mentioned, four of which involve murder and two suicide.. As I said before, the level of analysis of the books is really noteworthy and any Christie fan should really have a copy of this volume as they will find it fascinating. The third section looks at the history of barbiturates in general, from their discovery to their usage in medicine and beyond. This also includes an explanation of how the drugs work, how they interact with the body and the effects that will be seen both whist being administered, the aftereffects and detection at autopsy if possible if they are used to kill. There is also a section on how they kill rather than just provide medical assistance. this can be a bit technical but Harkup explains things in as simple a way as practical for the non-chemist. This is then followed by consideration of any antidotes or remedial processes from an overdose. We then look at other real life cases to better understand the problem of the poison administered and finally a look at Christie’s own experience with handling the drug. An excellent and comprehensive overview both of the poison itself and how it featured in Christie’s books and in the real world.

The chemicals looked at in this volume are the eponymous Arsenic then Belladonna, Cyanide, Digitalis, Eserine, Hemlock, Monkshood, Nicotine, Opium, Phosphorus, Ricin, Strychnine, Thallium and Veronal. There is a second volume already out in hardback but as I have ‘A is for Arsenic’ in paperback I will wait for the matching book. But I’m really looking forward to ‘V is for Venom’ which is due out in paperback on the 24th September 2026.