I have to admit that in the over three decades I have owned this book, as part of a set of six novels by Hardy from The Folio Society, I have attempted to read it at least three times. Initially when I bought it back in 1993 and then again probably ten years later, where according to the bookmark I found inside I made it to page 84 out of 413, this time I read and thoroughly enjoyed the book in just four days during the last week. I don’t know why I failed the first two times, some books you just have to be in the right frame of mind to appreciate them.

There are five main characters, I’ll tell as much of the start of the novel to set out how they stand with each other. Gabriel Oak who starts the novel as a farmer in good standing with two hundred sheep and a couple of sheepdogs, the younger of which would lead to his ruin by one night driving his entire flock over a cliff edge to their deaths, The sheep were not insured but by selling everything he owned he managed to cover his debts. Also appearing at the start of the book is Bethsheba Everdene, a young woman whom Oak falls in love with, pretty well at first sight, but she does not return his affection. She however soon leaves the vicinity, before Oak’s disaster with the sheep, and he knows not where she has gone. Oak, now penniless takes himself off to a hiring fair hoping to get a job as a bailiff (farm manager), failing to do so he reverts to his skill as a shepherd but still doesn’t get a job so decides to try the next fair in a nearby town. On his way he sees a hayrick on fire and endeavours to put it out, his bravery is soon noticed by the labourers on the farm as they race to his assistance and on the back of this he is offered the job as shepherd by Mistress Everdene who it turns out had inherited this very farm which is why she left the area where Oak was living. Still very much in love with Bethsheba but now so reduced in fortune as opposed to her meteoric rise he realises that he can never hope to gain her hand in marriage.

On coming into the village after the fire is extinguished he encounters the young Fanny Robin who it turns out has that night left the house where she was employed as a servant without telling anyone and is running away to her love, a Sergeant Troy in one of the local regiments who has promised to marry her. Troy however is an out and out cad as will become obvious as the book progresses. This leaves one more major character, the owner of the farm adjacent to Bethsheba Everdene’s, Mr Boldwood, I don’t think we ever find out his first name. In a moment of fecklessness Bethsheba sends Boldwood a valentine one year even though she doesn’t love him and this prompts the bachelor to look again at his neighbour and consider marriage for the first time in his life and this will lead to all sorts of problems as the book progresses. These five characters with their interrelationships drive the whole plot but around them the description of rural life and its nearness to poverty is brilliantly told by Hardy, take the following example, which also shows the expression of the local dialect which pervades the novel, this is just after Oak has been retained as shepherd after his heroics with the fire.

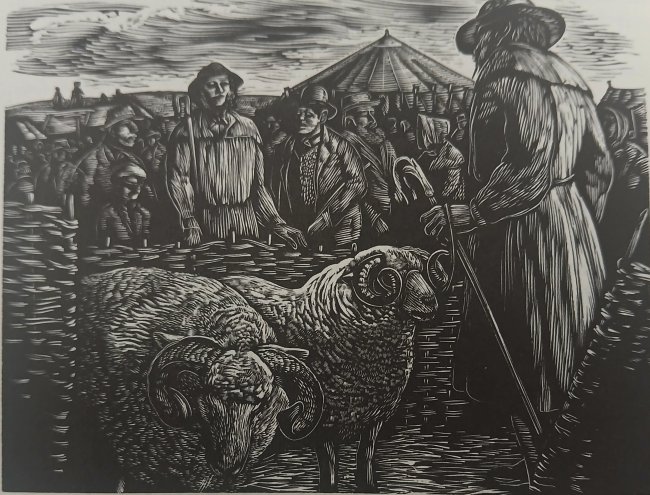

The book, like all Folio Society editions, is beautifully illustrated, this time with thirty one wood engravings by Peter Reddick who worked on all of their Thomas Hardy volumes, around twenty of them, making him the first artist to completely illustrate Hardy.

It was only at the end of the book that it dawned on me how young the major characters are, Gabriel Oak is one who is given a definite age, that of twenty eight at the start of the novel which covers the span of around four or possibly five years so he is thirty two or thirty three at the end of the story. There then becomes the slight problem of the age of Bethsheba Everdene caused by two statements by Gabriel which disagree. In chapter twenty nine – Particulars of a Twilight Walk he says he is six years older:

But in chapter fifty one – Bathsheba Talks with Her Outrider he says there is eight years between them and Bethsheba agrees:

As she agrees and she knows him better by now, as it is near the end of the book, I’m inclined to the eight year gap meaning she was twenty at the start of the novel and twenty four or twenty five at the end. Suddenly it dawned on me just how young she was when she inherited the farm and started running it by herself and that brings a new perspective to her fearlessness and possibly recklessness in deciding to do that. Mr Boldwood is described as ten years older than Oak so allowing for Oak’s approximations in the earlier passage we can say he is in his early forties by the end, which fits with his position as a confirmed bachelor early on in the narrative as he would hardly be described as such if much younger than his late thirties. Sergeant Troy is stated as twenty six at the end of the book and Fanny Robin is twenty, so she was just fifteen or sixteen when she started her relationship with Troy. However I can’t include a picture of where these ages come from without giving away a large part of the end of the book, which I don’t want to do.

I’m so glad I had another go at reading this book and I’m now not sure why it has taken me so long to finish it as I have greatly enjoyed this tale of Victorian life in south west England, so much so that I’m considering which one of the other six Hardy novels I own to tackle next.