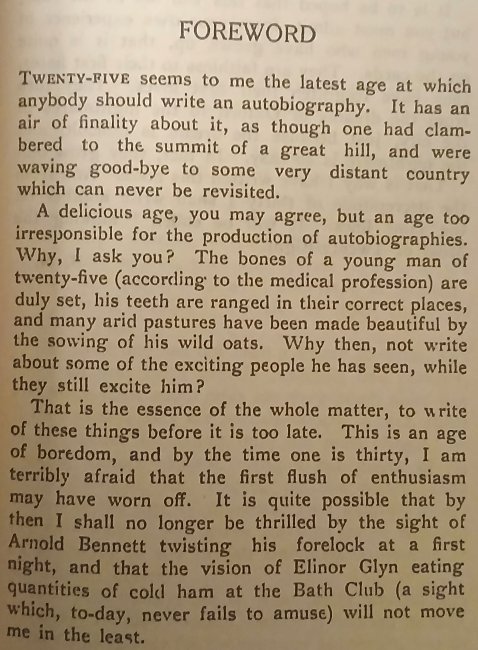

Continuing my plan to read the first ten Penguin Books during the twelve months after their ninetieth anniversary of when they were published, I have now reached book seven and the second one in the blue covers of biography in that initial set after book one ‘Ariel‘. We wouldn’t see a new colour until book thirty one in March 1936 when the purple of Essays and Belle Lettres first appeared on HG Wells’ ‘A Short History of the World’ and there wouldn’t be another book classified as Essays until number 444 ‘The Times Fourth Leaders’ in July 1945. However back to this book, and I have to admit I knew nothing of Beverley Nichols, to the point that I was surprised to discover that he was male despite the more usually female first name. I was also not inspired by the idea of a twenty-five year old writing their autobiography, so was not particularly looking forward to the book, but I’m so glad I read it. Nichols started to win me over even in the foreword:

And meet interesting people he certainly did, by page fifty we have encountered US Presidents Wilson and Taft, along with poets John Masefield, Robert Bridges and WB Yeats and are about to have conversations with both GK Chesterton and then Minister of War, Winston Churchill. Nichols was born in 1898 and the narrative runs up until 1924, he was therefore involved in World War I, but luckily was not called up to the front rather his Oxford University education was interrupted by working in the intelligence section of the War Office and then as Aide-de-camp to Arthur Shipley on the British University Mission to the United States, which is how he met the two Presidents. On return to the UK he resumed his delayed time at Oxford and became president of the Oxford Union, which is how he subsequently met so many other people of note at the time and as it was normal for the president to take people to dinner before the evening debates he would spend several hours in their company. He also ran a student magazine, which Masefield, for instance, contributed to, so even in his early twenties Nichols was remarkably well connected. This is the joy of the book, it is not so much an autobiography but a series of reminiscences regarding the various people he met, you learn far more aout them than you do Nichols himself.

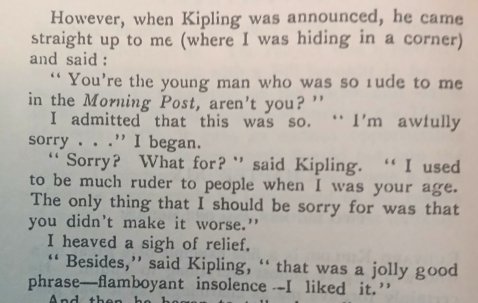

After leaving university Nichols eventually became a theatre critic giving him access to even more people but before that he spent some time as secretary to Australian opera star Dame Nellie Melba and there are numerous stories relating to those experiences included in the book, which like a lot of his anecdotes are really quite funny. One I particularly like has Melba taking a dislike to the position of some stone vases in a hotel and deciding to move them to a more ‘artistic’ formation which she duly did by strenuously pushing them up towards a wall much to the confusion of the staff. Typically for the lack of significant information about himself Nichols doesn’t mention that he was Melba’s secretary he just seems to spend quite a bit of time with her in Australia with no context given. Nichols also met Rudyard Kipling whom he had disparaged in a letter a couple of years earlier and then to his horror saw Kipling enter a room he was in:

The book is great fun and if I did have to look up a few people whose fame has somewhat died down in the intervening century there wasn’t many of them and it was worth the reference time but it is well written, amusing and far better than I expected it to be. Let’s leave the final words to Nichols, who did go on to have a long life as an author of over sixty books, using the final sentences of the book:

Again – I have done. Twelve o’clock strikes. There really should be slow music playing outside my window, so that I might work myself into a frenzy of pathos at the thought that another day has arrived to carry me on to middle-age. I should rather like to stay, just a little longer. But then – better not. Accept the joke of life for what it is worth. It is not such a very brilliant one, after all. And was there not a man called Browning, who wrote. “Grow old along with me, the best is yet to be.”