This blog follows on from Part 1 but goes through the entire plot line so should not be read if you have not previously read the book or do not mind knowing what happens.

The book is split into six chapters and each is effectively a stand alone tale dealing with a specific period in Orlando’s life. The first chapter makes perfect sense as you read it, Orlando is a boy when Queen Elizabeth I visits his fathers’ great house and so captivates Her Majesty that he is invited to court towards the end of her reign, where he grows up to be a young man about town and is still around the court when James I becomes king after the death of Elizabeth. By the end of this chapter you are happily reading a novel set in the time of the Stuarts where Orlando has loved and lost the Russian noblewoman Sasha and you are wondering what will befall him next.

Chapter two has him exiled from court due to the scandal with Sasha and spending time back in the family house attempting to write great works but being unsatisfied with them all and holding parties. This is a not so subtle reference to Virginia’s lover Vita Sackville-West who is also trying to write ‘a great work’ but Virginia doesn’t rate her as an author and doesn’t believe she is capable of achieving this ambition. Orlando also at this time meets Romanian Arch-duchess Harriet who attempts to seduce him but without success. Ultimately Orlando is getting bored stuck at home so that he requests a job from the King and is sent as ambassador to Turkey. This is also a reference to Vita as she lived in Constantinople (as it was then) when her husband was sent to the embassy there from 1912 to 1914.

If you know English history a few comments in the book may be ringing bells by now but the storyline still flows without many issues. The third chapter deals with his time in Turkey initially as ambassador but then the book takes a dramatic swerve. There are a few pages that read like sections of an ancient Greek play, with Purity, Chastity and Modesty introduced as characters parading through his bedroom with trumpet calls and overblown narrative until Orlando finally awakes as a woman. As a plot twist it is certainly unusual and gets odder as people seem relatively unfazed by the change and as the embassy had been attacked during an uprising whilst Orlando slept he/she goes off to live with gypsies for a while. This last part is again a link to Vita who had a highly romanticised view of the Romany people as free living and unconstrained by the pressures of modern life. The book has her living with them for a while and then realising that she is really an interloper and misses the green lands of her home, this is Woolf pointing out to Vita that for all she may fantasise about the gypsy life she would not cope with the reality.

Chapter four has her decide to return to London and her home in Kent where she again meets the Arch-duchess who reveals herself to actually be Arch-duke Harry and this time as a man tries to seduce the now female Orlando with much the same result. Again nobody appears to be surprised by this. She throws herself into London society and meets many famous writers before taking to disguises to explore the seedier side of London to stop life getting too dull. By the end of this chapter the aspect of the book that was ringing bells earlier has now been made explicit but without any explanation, I’ll get to it later. The fifth chapter takes place entirely in the great house without providing much detail as to what goes on. By the end however the court cases started when she returned from Turkey as a woman and caused all sorts of issues with who owned what and if she really was Orlando are settled although they have used up most of her fortune and she marries somebody she has barely got to know just in time for him to leave to go to sea.

The book ends with her finally finishing her great work “The Oak Tree” and it being praised and even winning a prize before her husband returns to her from foreign climes and she rushes to greet him.

This cover is a bit problematic for me as the inclusion of the aircraft gives away the one aspect I left out in the summary above and that is the time travelling aspect of the novel. You start reading the book and it is clearly set at the end of the 1500’s with the reign of Elizabeth I coming to an end. Orlando is mentioned several times lying under the tree so what is the plane doing there?

In fact you slowly become aware of the drift of history through the book. As stated above Orlando was clearly a young man at the end of Elizabeth’s reign and much later on in the book we discover that the poem he has been working on since boyhood is dated 1586, so that would probably place him as born in around 1575, Elizabeth died in 1603 and we know he was at court during her reign for a period of years. The next monarch mentioned is James I (1603 to 1625) during whose time Orlando is largely banished from court after his relationship with Sasha at the frost fair. There were two of these during his reign (1608 and 1621) so Orlando is roughly 33 or 46 at this point. The first of these sounds more likely from his behaviour so let us say he retires to his country house in 1608, this is all quite plausible up to this part of the novel.

The next time period mentioned is when he goes to be Ambassador to Turkey after getting tired of being at home. I’m not surprised he was getting bored by then as the Monarch he asks for the job is King Charles II (he is described as being with his mistress Nell Gwyn so we know which Charles we are talking about). His reign was from 1660 to 1685 and he started his relationship with Gwyn in 1668 so as a minimum Orlando is now 93 and has spent at least the last 60 years holding parties at home. This is the first time that the time-scale appears to have stretched, as up until he goes home in 1608 it is quite believably a tale about a late Elizabethan gentleman, nobody appears to be surprised by this and he is still clearly a young man in the novel. Charles II is still on the throne when Orlando is made a Duke and subsequently changes sex. We then hit her time with the gypsies and this is also clearly several decades. On return to England she sees the dome of the new St Paul’s cathedral (consecrated 1697) and the captain of the ship refers to the late William III (died 1702) so we are now in the reign of Queen Anne (1702 to 1707) and this is explicitly stated later in the book as Orlando enters society as a young and eligible woman at the age of 130!

At last a positive date… Well sort of. There is a mention of 16th June 1712 being a Tuesday, it was actually a Thursday but never mind, it is the first specific date in the novel and this is when Orlando decides to quit society only to decide not to the next day due to an invitation that she really wanted to go to. There she meets Alexander Pope and through him various other writers such as Swift who quotes from Gulliver’s Travels, a book printed in 1726 so time is still moving on apace. She sees Johnson and Boswell (circa 1770’s) and chapter four concludes with the dawning of 1st January 1800 with a dark cloud over London. Chapter five includes a statement that she had been working on the poem “The Oak Tree”

… for close on 300 years now. It was time to make an end.

so that takes us up to the 1860’s. This is another huge leap in the time line of the book as it is only 8 pages into the chapter. It’s an odd chapter, using damp weather as a metaphor for the changes in society through the Victorian age, no more gay parties and bright lights, now the houses are cluttered and cold, the people withdrawn and everything is dark and covered up as society becomes more straight-laced and women are expected to be ‘the little woman at home’ safely married off. It’s also no wonder the court proceedings have used most of her fortune, they would have started in the early 1700’s and concluded roughly 160 years later as Lord Palmerston and Gladstone are mentioned with the court documents and Palmerston died in 1865. It is worth noting however that it does leave Orlando with the house, which as I stated in the previous essay on the book Vita specifically didn’t get as she was a woman so maybe this is a put in as a solace to Vita that although it may take 160 years a woman will eventually inherit what would be hers by right if she had been a man.

The sixth, and final, chapter brings us to the present day, well 1928 which is when the book was written anyway. It begins slightly before then at the end of the Victorian age as she finally gets her poem The Oak Tree published with the help of Nicholas Greene but most of the chapter is set on the 11th October 1928 starting in London with a very confused shopping trip. She drives out of London to the great house in Kent and is there as her husband finally comes home this time by aeroplane whilst she lies under the tree as she used to as a boy centuries earlier

It is not only Orlando who straddles time in the novel, several of the fictional characters fail to grow old with her, the Arch-Duchess/duke is also mentioned in chapter five as married and settled in Romania so he is also as old as Orlando and others survive well beyond a normal lifespan such as Nicholas Greene, the poet and critic who first met Orlando in the Elizabethan age and meets her again in the Victorian. Sasha from the frost fair in 1608 is also glimpsed during the shopping trip in 1928 and is described as late middle aged. Orlando’s husband, Shelmerdine, is also timeless, at least since coming into contact with Orlando, for they meet and marry in the 1860’s when her court cases have completed but he is clearly still only in middle age by 1928.

The book is complex and at times infuriating as it leaps about but still an enjoyable read, I’ve also had quite a bit of fun reading through it again trying to identify all the historical events that can be dated for this essay.

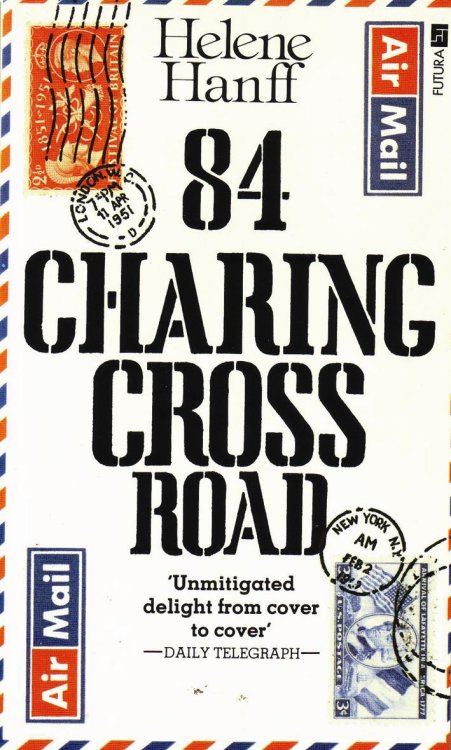

Welcome to my book shelves, home to some 6500 volumes dating back to the mid 1700’s right up to the present day. I’m going to use these as the basis for short essays or reviews not just of these books but where ever they wish to take me. The aim is to pick a book, or group of books each week and look at its significance, or just tell a tale as to why it has found itself here.

Welcome to my book shelves, home to some 6500 volumes dating back to the mid 1700’s right up to the present day. I’m going to use these as the basis for short essays or reviews not just of these books but where ever they wish to take me. The aim is to pick a book, or group of books each week and look at its significance, or just tell a tale as to why it has found itself here.