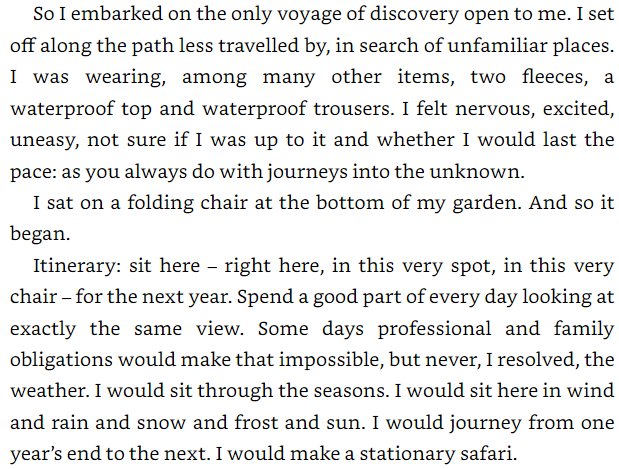

The fourth book in my natural history themed August reading material is a book I originally used as reference material. Although entitled Galápagos Diary, this book is far more than a journal of a 1995 trip round most of the islands in the Galápagos archipelago by artist and author Hermann Heinzel and teenage photographer Barnaby Hall. The book was first published in 2000 and you can see why it took so long to come out as it is a truly beautiful book, heavily illustrated with sketches and photographs. But the reason I bought this copy in 2002 is that I travelled to the Galápagos that year, to mark a significant birthday, and needed a guide to the wildlife, especially the birds. Heinzel I had already heard about as he has illustrated several ornithological volumes including the classic Collins handbook ‘Birds of Britain and Europe’. Originally born in Germany, Heinzel has lived for many years in France and knew Rod and Jenny Hall and their son Barnaby, Jenny and Barnaby had been to Galápagos in 1994 and Barnaby assured Heinzel that he had seen Cattle Egrets there which surprised the naturalist who suspected that what he had really seen was Great Egrets but Baranby was certain so they decided to go together during the school holidays the following year and so the expedition was planned. Not only to see if Cattle Egrets had indeed made it to the islands but also to attempt to see all the endemic species of birds to be found there.

The book is split into three sections, pages 1 to 158 cover the diary of their travels with lovely hand drawn maps showing where on each island they stopped, with drawings and photographs mainly done at the time. A sample page, seen above, deals with part of the time they spent travelling around one of the inhabited islands, San Christobel, the birds drawn by Heinzel are North American Bobolinks which as the name implies are visitors to the islands rather than endemic. Below is a page featuring what for me was the most surprising bird I saw in Galápagos, the endemic Galápagos Penguin. Bearing in mind the island group is on the equator I really wasn’t expecting to see penguins but these photographed by Barnaby on Bartolome, which is where I also spotted them, prove that sometimes animals are not where you think they should be.

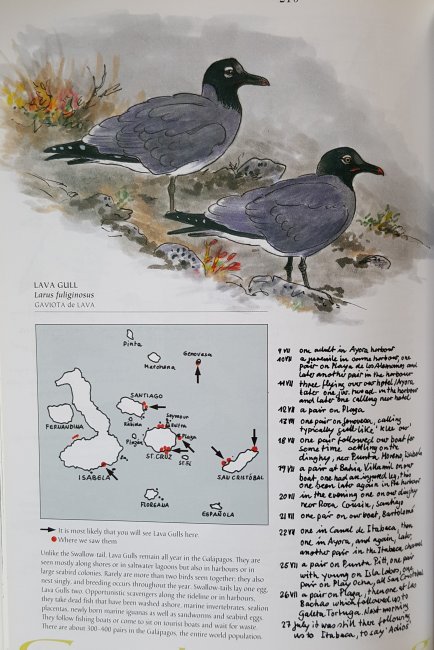

The next section is the species guide and takes up pages 159 to 261, this is entirely done by Hermann Heinzel using sketches and completed paintings of each of the endemic species, no photographs are used in this section. On this trip they failed to see just 3 of the 59 types of breeding species of bird on the islands, just the Marsh Owl, the Painted Rail and the rarest of all, the Mangrove Finch eluded them. In all they saw 66 species and they were all sketched by Heinzel and the three breeding birds they didn’t find had been seen and drawn by him on previous trips so it is a complete guide. Along with the drawings you get a map where they spotted the bird and notes relating to each sighting. The page below is for the Lava Gull, a bird that seems to be everywhere as you can tell by the notes which state that they saw examples on half the days they were in the Galápagos and I spotted them on multiple occasions.

The final section is a nine page checklist of Galápagos birds, both endemic and visitors which invites you to tick off species as you see them but I couldn’t bring myself to do so. It is not just a list but also includes which islands they are to be found on. Despite being able to fly, with the exception of the penguin and oddly the cormorant which has become flightless since arriving in the island group, the birds tend to stick to specific islands where their needs are best catered for. The islands have surprisingly different habitats even though they are a relatively small group and a tiny number of species can be seen from every island, even including those that can be expected to be seen going past.

It was a very useful book when in Galápagos and also later on trying to identify each bird I photographed. Perhaps surprisingly I have no memory of actually reading the diary at the time, I appear to have just used it as a guide to tell what I had been looking at. That is definitely a pity as it is an interesting read as well as a beautiful book.

If you are interested in the photographs I took in 2002 they can be found here: