As this blog is being published on Christmas eve, I have taken the opportunity to review another of the privately printed Christmas books given by Alan and Richard Lane as gifts, in this case the book for Christmas 1951. I’m not going to attempt to review the gospel itself, this blog is concerned with the new translation, this edition of the translation and this book in particular. Penguin were to publish a new translation of The Four Gospels by E V Rieu a year later in November 1952 so this was a first view of this very readable new translation. It was a little odd to select the gospel of Mark as a Christmas gift as only Matthew and Luke include the birth of Jesus, which you would have thought would have been a consideration, but as you can see below Mark starts with the adult Christ being baptised by John in the River Jordan.

Mark is one of the three synoptic gospels where the same stories are told in much the same sequence and in similar words, indeed three quarters of Mark’s gospel also appears in those of Matthew and Luke whilst the gospel of St John is quite different both in style and content. As I said earlier the big difference is the lack of a nativity story in Mark but you also don’t get the Sermon on the Mount or several parables amongst other items in Mark which is quite a bit shorter than the other three gospels.

Looking at the first page as translated by Dr. Rieu it is clear that it is written as much more of story than the classic King James translation which I grew up with, which for all its magnificent prose can be a little daunting to approach, particularly for a modern reader. By way of contrast this is the same passage in the King James version.

1:1 The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God;

1:2 As it is written in the prophets, Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, which shall prepare thy way before thee.

1:3 The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.

1:4 John did baptize in the wilderness, and preach the baptism of repentance for the remission of sins.

1:5 And there went out unto him all the land of Judaea, and they of Jerusalem, and were all baptized of him in the river of Jordan, confessing their sins.

1:6 And John was clothed with camel’s hair, and with a girdle of a skin about his loins; and he did eat locusts and wild honey;

1:7 And preached, saying, There cometh one mightier than I after me, the latchet of whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and unloose.

1:8 I indeed have baptised you with water: but he shall baptize you with the Holy Ghost.

1:9 And it came to pass in those days, that Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee, and was baptized of John in Jordan.

1:10 And straightway coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens opened, and the Spirit like a dove descending upon him:

1:11 And there came a voice from heaven, saying, Thou art my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.

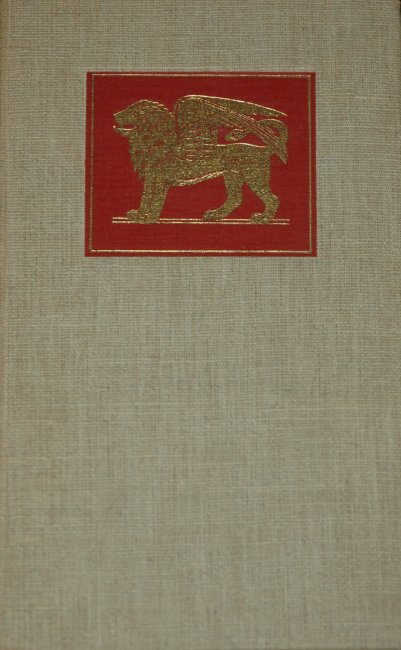

It is almost forty years since I first read E V Rieu’s translation of the four gospels. I took it, along with a couple of others from the Penguin Classics series, as my in flight reading for the first time I crossed the Atlantic in February 1986. I’m not remotely religious although I did go to a Church of England primary school for my education between the ages of four and eleven, but the way the gospels are presented in this translation means you can read them more like a collection of four novellas and enjoy the stories as they are told. This edition is really beautifully produced with canvas covered boards and terracotta cloth labels blocked in gold. The pages are a lovely grey and compliment the overall design by Hans Schmoller well. The lion design by Reynolds Stone is different to the one, also engraved by him, used for the Penguin Classic when it was finally published.

My copy was given to typographer Ruari McLean (it has his bookplate inside) who had joined Penguin Books in 1946 with specific responsibility for Puffin books and was instrumental in introducing Jan Tschichold to Penguin. By 1949 he had moved on and was working with Rev. Marcus Morris on the design of a new comic for boys he had devised called Eagle, which would go on to massive success in the 1950’s and 60’s. Tschichold would radically redesign Penguin books in the late 1940’s and came up with The Penguin Composition Rules.