I’ve always liked Shakespeare, whose first play was performed in the 1590’s, but didn’t really know much about who came before him so decided to pull this volume from The Oxford History of Literature off the shelf and actually read it, rather than my usual use of books from this set which is as reference material. I was quite surprised to discover that this volume at least is quite readable so I’m now tempted to complete the set, as I currently only have ten of the fifteen volumes that take the history of English literature from Middle English in 1100 to 1400 through to the early twentieth century and DH Lawrence. Firstly a little bit about the history of the hundred years covered in this book as the choice is quite deliberate. The year 1485 saw the crowning of Henry VII after the fall of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field and the end of the War of The Roses between the houses of York and Lancaster over which should rule England. Henry VII (Lancaster) married Elizabeth (York) linking the warring families and founded the Tudor dynasty which would rule for the next 118 years. We then see Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and finally Elizabeth I, who was the last Tudor monarch, reigning from 1558 to 1603, so the period covered in this book is almost the entire Tudor dynasty but ending before the great flowering of English drama at the end of the reign of Elizabeth I as this has its own volume.

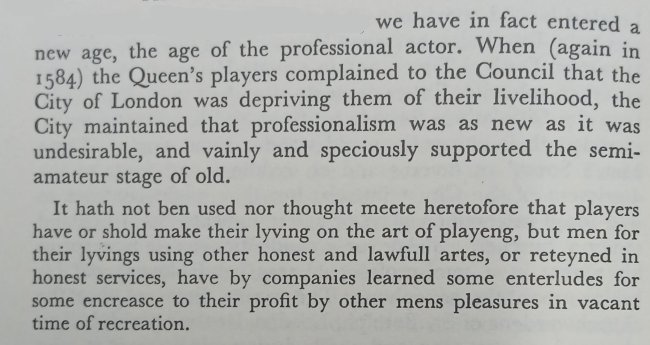

The period starts with the tail end of the countrywide performances of religious Mystery and Passion plays which had started as instruction to the populace centuries earlier (think of the still performed decennial Oberammergau Passion Play for a modern example) and leads us through the development of other subjects beyond religion becoming the basis of performances both comedy and tragedy along with the first appearance in England of professional actors. In 1485 there were no companies of players, plays were normally performed by children, often cathedral choristers or pupils of the Grammar schools, which would be given at the royal court or in their own halls. For adult performances there would be plays by teachers at the universities (primarily Oxford and Cambridge) and oddly by members of the four Inns of Court, presumably due to the eloquence of professors and barristers. Indeed members of both the Inner Temple and Middle Temple are referred to many times throughout the book as performing plays especially at Christmas. No dedicated theatre as such existed in England until the last decade or so covered by this book and it was only then that adult actors started to outnumber child performers and professionalism began to gain ground.

But let’s get a flavour for the plays being performed, these were often inspired in structure and sometimes in subject by the Roman playwrights Terence and Seneca with the latter being the dominant influence as the century progressed, at the end of the 1400’s Latin was still used but the English language was beginning to be more common for plays. driven by its rise in poetry and song. For an example of the sort of thing you would have encountered at the end of the 15th century with a playwright better known as a poet John Skelton’s Magnificence, a five act play of 2,567 lines with a distinct moral theme.

One aspect of plays of this period is that characters rarely had ‘normal’ names instead they would be called after the vice or virtue that they represent, a good (or possibly bad as I’m sure I wouldn’t want to see the play) example of this is Lupton’s ‘All for Money’ the essence of the plot is described below:

etc. I’m sure you get the idea. The plays would be in verse, with probably the most clunky format, the fourteener, which was very popular at the time. Blank verse would not make its appearance until the late 1550’s and even then would barely have an impact in the morality plays which were still being written.

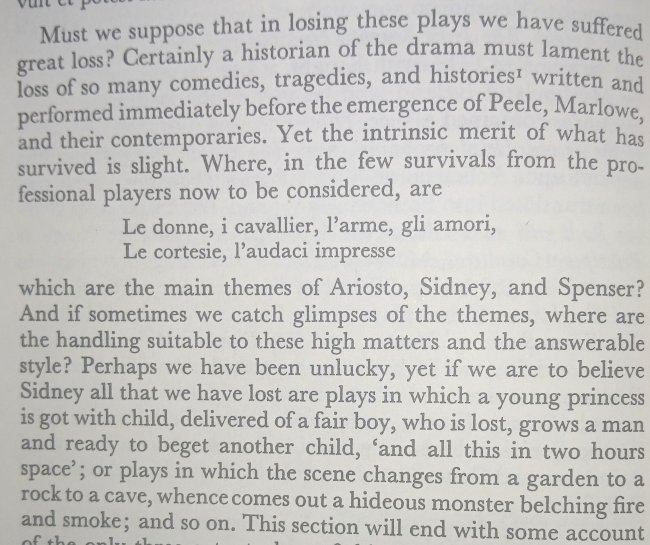

The comedies that start to appear in the 1540’s by playwrights such as Udall from Eton College who wrote Jack Juggler and Roister Doister, two of the better plays of the period that would stand up to modern performance which frankly most of the works covered in this book would not. Tragedies however would need to wait for later writers before becoming suitable and not something that audiences would probably walk out of from boredom. A lot of the plays of the period only exist as titles, so much has been lost but the authors of the book are not dismayed by this as they say themselves:

Dramatically the hundred years covered here yield little of real substance but they set the ground for what was to follow and as the Elizabethan proverbs say “a bee sucks honey out of the bitterest flowers” and “out of a little spark came a great flame” within a decade we would have Christopher Marlowe (Dido and Tamburlaine both 1587), Ben Jonson (various minor plays he didn’t really get going until the late 1590’s) and of course William Shakespeare (first play Richard III – early 1590’s date uncertain). It has definitely been an interesting read even though it has given me little in the way of encouragement to delve into the plays of this time themselves. The massive leap in quality of play-writing and indeed performance at the end of the Elizabethan period is remarkable and it is no wonder that Shakespeare is still the most widely performed author in the world.

The volumes I have so far, quite an attractive set.