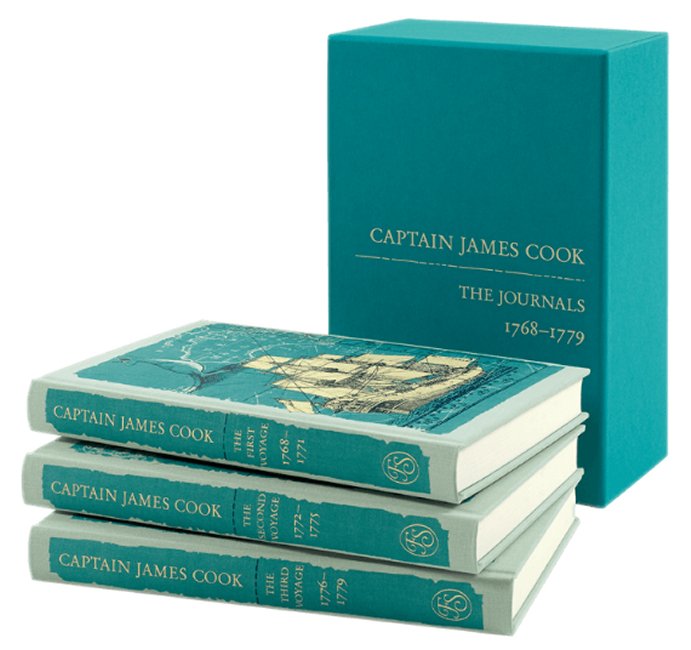

The fourth week of August, and Cook only did three voyages of exploration so what to do here, well as the second voyage carried watches to test new ways of calculating longitude with varying levels of success as I will cover below it only seems fair to delve deeper into just what was being tested and why, fortunately Dava Sobel has written this excellent summary of just what was going on and how a group of astronomers colluded to keep John Harrison and his son William from winning the main prize.

As I said a couple of weeks ago “Cook had a watch made by Larcum Kendall which was a copy of that designed by John Harrison and alongside this a watch made by John Arnold, Ferneaux had two watches made by Arnold,” It may seem odd that the original clock by Harrison didn’t go on the 1772 voyage seeing as he was the one in line for the £20,000 prize (over £2.5 million for the modern equivalent according to the Bank of England inflation calculator) but the Board of Longitude were by then determined that he shouldn’t succeed and insisted that the original was effectively held hostage by them whilst a, hopefully inferior, copy was sent instead. But we are getting ahead of the story, let’s go back a few decades.

Dava Sobel presents the development of H4, the superb watch made by Harrison, by starting at the very beginning with explaining the problem of determining longitude. How far up or down the Earth you are is relatively easy to determine but longitude, how far round the Earth from your start point is a lot more difficult as you either need complex astronomical readings and their subsequent calculations and it could easily take four hours to work out where you roughly are using that method; or an accurate indication of the time in your home port to compare with local time which you could get from when the sun was highest in the sky which would be noon. Local time changes as you go round the world with a full twenty four hours representing a circumnavigation so an hour difference would be equivalent to fifteen degrees of longitude away from home. The problem was that no clock would work accurately on a ship due to temperature and humidity changes along with the movement of the ship and it had to be accurate as just a minute out would drastically alter the determination of longitude.

John Harrison, a self taught clock maker from the north of England starting to construct his first clocks back in 1713, a year before the Longitude Act setting out the prizes for determining longitude was passed. His clocks were, most unusually, mainly made of wood rather than the more common brass and most still exist with his fourth, the clock at Brocklesby Park, built in 1722 still running and telling excellent time today. Harrison’s first encounter with the Board of Longitude would be in 1730 when he went to London to present his early plans but he couldn’t find them as they had yet to meet due to no sensible proposal being sent for them to consider. That it took until 1773 for him to be finally awarded half the money he was fully entitled to and then only following intervention by the King is a scandal that Sobel covers so well in this book. Admittedly Harrison himself was partly to blame for the delay as he kept seeing improvements he could make and wanted but most of the problems were down to astronomers, especially Maskelyne, who were determined that solving longitude via lunar observations was the only way forward and as they were on the Board they kept changing the rules in order to prevent Harrison winning.

The story of the determination of longitude sounds like a fairly dry subject but it is anything but and this is one of the most interesting books I have read this year.