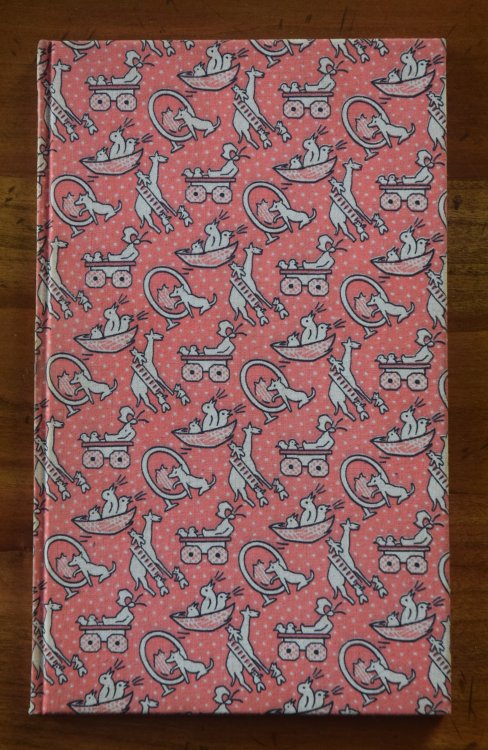

This autobiography in verse covers Betjeman’s early life from his Edwardian childhood (he was born in 1906) to his university days at Magdalen College in Oxford where he was taught by C.S. Lewis. The book was first printed in 1960 just as Betjeman was getting serious recognition as a poet with a dozen volumes published before this and it is also the year he received The Queen’s Medal for Poetry and was made a CBE. The verse has his characteristic humour but also darker times like describing being bullied at school. It is uncharacteristic also in being, for the most part, blank verse, though he can’t stop himself at times, from adding in some parts in rhymes. The book is split into nine chapters as we follow him growing up.

We start in Highgate where the family had moved when he was three years old, they were clearly relatively well to do as they owned a four wheeled carriage and regularly holidayed in Cornwall. Apart from Maud, his overbearing nurse, who seemed to delight in punishing him for slight misdemeanors he appears to have had a happy childhood up until he went to school. Apart from one traumatic incident that clearly haunted him right up to his fifties when he wrote the lines on just the second page of Summoned by Bells.

Safe were those evenings of the pre-war world

When firelight shone on green linoleum;

I heard the church bells hollowing out the sky,

Deep beyond deep, like never ending stars,

And turned to Archibald, my safe old bear,

Whose woollen eyes looked sad or glad at me,

Whose ample forehead I could wet with tears,

Whose half-moon ears received my confidence,

Who made me laugh, who never let me down,

I used to wait for hours to see him move,

Convinced that he could breathe. One dreadful day

They hid him from me as a punishment:

Sometimes the desolation of that loss

Comes back to me and I must go upstairs

To see him in the sawdust, so to speak,

Safe and returned to his idolator.

His father was the third generation owner of a silversmith and cabinet making business and was very disappointed in John because he refused to carry on the firm and all this is covered in the second chapter of the book. In this edition each of the chapters has a small line drawing by Michael Tree and a brief summary of what will be covered. The description of the workshops for the business in this section and the hours that John spent clearly enjoying himself with the craftsmen employed there made it all the more galling for his father when he later expressed no interest in continuing it

To all my father’s hopes. In later years,

Now old and ill, he asked me once again

To carry on the firm, I still refused.

And now when I behold, fresh-published, new,

A further volume of my verse, I see

His kind grey eyes look woundedly at mine,

I see his workmen seeking other jobs,

And that red granite obelisk that marks

The family grave in Highgate cemetery

Points an accusing finger to the sky.

Chapter three has him at school and being bullied at both his junior schools, he seems unclear why at the first one but at the second his apparently German surname in 1913/4, spelt then Betjemann, led to him being picked on by gangs and having to come up with various routes home to avoid them. Ironically the family was actually originally Dutch and the additional ‘n’ was added when they came to the UK over a century earlier but soon Britain was at war with the Netherlands, so they wanted to appear German. During WWI the second ‘n’ was quietly dropped again. Chapter four and the family is on holiday in Cornwall leading to the start of the young Betjeman’s love affair with railways and the English countryside.

Chapters five and seven describe his private education, first at Dragon preparatory school in Oxfordshire and then Marlborough college in Wiltshire. His time at Dragon appears to have been pretty happy and exploring by bicycle leads him to churches and that other great love of his throughout his life, architecture. Marlborough however was a more difficult time, there are stories of beatings and the prefects birching the boys and terrorising them as a group known to the younger boys as “Big Fire” because of where they sat in the evenings. A boy who had transgressed would be called to “Big Fire” for a beating or sometimes worse. I skipped chapter six which covers being back in London during holidays exploring the London Underground and buying books, the family had moved to Chelsea and the bookshops abounded

Untidy bookshops gave me such delight,

It was the smell of books, the plates in them,

Tooled leather, marbled paper, gilded edge,

The armorial book-plate of some country squire

I’m with Betjeman all the way with those sentiments.

The summary above of chapter eight pretty well covers it, his father is even more dominating than before but now John is big enough to escape and does so on long cycle rides round the area discovering yet more churches.

The final section deals with his years at Oxford, a place he freely admits to doing little or no work at and certainly not studying for his degree. Instead he builds a wide social network which become extremely useful to him in later years

No wonder, looking back, I never worked.

Too pleased with life, swept in the social round,

I soon left Old Marlburians behind.

(As one more solemn of our number said:

“Spiritually I was at Eton, John”)

I cut tutorials with wild excuse,

For life was luncheons, luncheons all the way-

And evening dining with the Georgeoisie

How much of this lack of drive towards his degree was down to the mutual dislike between himself and C S Lewis it is difficult to tell, it’s quite possible that even with a more sympathetic tutor who may have got more out of him he would still have left without a degree. In the poem he blames a failure of the compulsory divinity course but in reality he really put so little effort into his studies that he was never going to pass.

The book is a fun read and so unusual in the use of verse throughout. I first read it many years ago and had forgotten how much I enjoyed it.