To start off my latest August group of books, which this time is focused on natural history, I am beginning with a classic of the genre, Gilbert White’s The Natural History of Selborne first published in 1789, along with his Antiquities of Selborne, which initially was usually included but nowadays is largely omitted leaving just his famous work The Natural History. Both of these books consist of a series of letters, which in the case of Antiquities none of were never actually posted to anyone and in The Natural History several were also not posted but were instead created to match the rest of the content. The ones that were posted are to two different people over a period of almost two decades, but even these have been edited for publication so the whole is rather contrived. Gilbert White was the curate of Selborne on four separate occasions living in what was his grandfathers vicarage and his younger brother John, who is mentioned several times in the book as providing extra information was a vicar in Gibraltar. He is now famous for this book, which was one of the first true natural history volumes based on studies of wild fauna rather than dead examples. That is not to say White didn’t make use of freshly shot birds to complete his analysis but he was rare in studying live animals and how they reacted with the environment to give colour to his studies.

The book starts with forty four letters to the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant, the first nine of which were never posted and were written much later to form an introduction to the book when White decided to publish his notes on local wildlife and plants. These describe the village of Selborne and the surrounding countryside and so give a useful if somewhat tedious background to the observations that he then goes on to make. The second batch of sixty six letters are to English lawyer, naturalist and one time Vice President of The Royal Society the Honorable Daines Barrington and again several of these were never posted especially letters fifty six to sixty five, which are concocted from White’s daily journals and provide interesting details of weather extremes he has experienced in the village including winter temperatures of below zero degrees Fahrenheit (-18 degrees Centigrade) with ice forming below the beds in his house. These also include an account of the effect of a massive volcanic eruption in Iceland from June 1783 to February 1784 which killed around a quarter of the population of Iceland and left volcanic ash in the skies over Europe for months.

the peculiar haze, or smoky fog, that prevailed for many weeks in this island, and in every part of Europe, and even beyond its limits, was a most extraordinary appearance, unlike anything known within the memory of man … The sun, at noon, looked as blank as a clouded moon, and shed a rust-coloured ferruginous light on the ground, and floors of rooms; but was particularly lurid and blood-coloured at rising and setting.

Letter LXV

One of the frequent issues raised in the various letters is the possibility of bird migration, at the time this was merely a suggestion that it might happen with the majority view, including that of Barrington, being that birds that were not seen all year round hibernated through the winter even though no birds had ever been found in such a torpid state. White is in favour of migration but doesn’t believe that something as small and frail as a bird could travel long distances so keeps going back to the hibernation theory and indeed on at least one occasion caused a potential site for ‘sleeping’ birds to be dug up searching for them. Needless to say they found nothing. But his observations and attempts to understand the natural world from them was pioneering and one of the letters regarding the usefulness of earthworms was undoubtedly an influence on Charles Darwin a hundred years later when he wrote his monograph on the subject.

Four of the letters to Daines Barrington are in the form of monographs and were published in the Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society which is the worlds oldest scientific journal, started in 1665, and still in print. These four letters are by their nature longer and more detailed than the others and concern four related bird species which attracted White’s particular attention. Letter XVI is about House Martins, letter XVIII discusses Swallows, Letter XX details the habits of Sand Martins and letter XXI deals with Swifts. These are excellent articles on the differences and similarities between the four species and were ground breaking observations at the time (December 1773 to September 1774). In my opinion the letters to Barrington tend to be more interesting than the ones to Pennant which are more deferential to the addressee as Pennant had published several books on natural history including a four volume British Zoology. It is noticeable however that although there have been at least three hundred editions of The Natural History of Selborne and it has never been out of print since first coming out in 1789 I cannot find any currently in print editions of any of Thomas Pennant’s works.

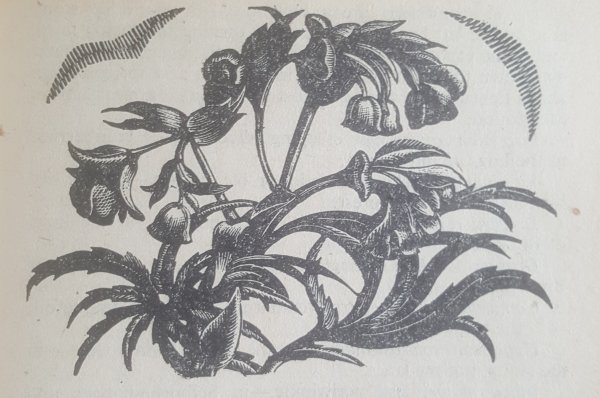

My copy is the Penguin Books first edition from March 1941, which was originally planned to be a part of a second set of Penguin Illustrated Classics following the original ten from May 1938 but this set never happened. However this explains why this book, along with Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, which will be covered later this year, has lovely wood engravings within the text, some of which I have included above, unlike other Penguin Main Series books which are just plain text as these two were designed before the continuation of Illustrated Classics was shelved. The engravings in this volume are by the wonderful artist Clare Leighton who despite being born and brought up in England had moved to America by the time she did these pictures for Penguin and where she continued to live for the rest of her life, dying in 1989 at the age of ninety one.