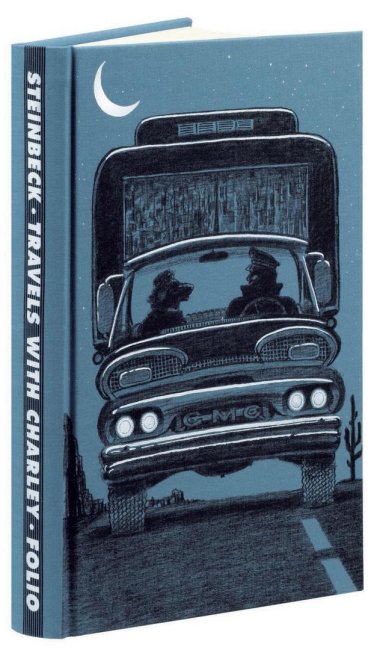

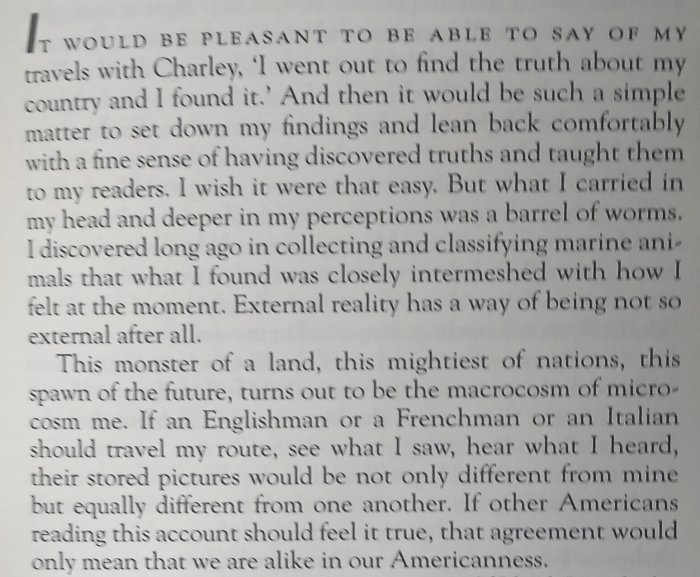

Towards the end of his life Steinbeck felt the need for one last adventure, this was 1960 and he would die of heart failure in 1968 aged just 66. His wife had long been concerned about his health and his heart condition, brought on by his heavy smoking had flared up several times in the preceding years and she was worried about his plans to travel right round the country in a converted camper van with his standard poodle, Charley, as theoretically his only companion. But Steinbeck wanted to reconnect with America, as he says at the beginning of the book:

The plan was to drive up from New York into Maine and explore the back roads of that sparsely populated state before heading along the Canadian border and into Canada by Niagara Falls, before coming back into the USA and travelling up through Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota then along the northernmost border to the coast, trying to stay off interstate freeways as much as possible. The first stumbling block was going into Canada with Charley, the Canadians were fine but, as is still the case, the USA border patrol were not, so Canada was dropped from the route. The less busy roads were also too slow so freeways appear more and more as the journey went on, but those kept him away from the people he wanted to talk to to see how their lives were changing so a sort of compromise was decided on where open countryside was driven through as often as practical.

The book when it came out in 1962 was a hit although it soon became clear that although Steinbeck had genuinely driven around the USA the text was less a travelogue than a carefully created artifice. That’s not to denigrate the book or the stories it tells, which are funny and at times distressing and provide considerable insights into how America had changed over the decades since Steinbeck had left his native California for the east coast and New York State. But it should be taken into consideration that Steinbeck was a great novelist, he was to win the Nobel prize for Literature just after this book came out, and probably couldn’t resist moving stories around and inventing dialogue to make his point. Also the actual trip was considerably more luxurious, and less lonely, than made out in the book, of the seventy five days he was away from home he spent forty five in hotels with his wife, Elaine, and on more than half of the remaining thirty days he either stayed in motels or trailer parks or parked the camper van at the home of friends. Steinbeck’s son, also called John, said that his father invented almost all of the dialogue whilst writing the book but frankly I don’t care, it’s a fun read and you do learn a lot about America on the turn of the 1950’s into the 1960’s.

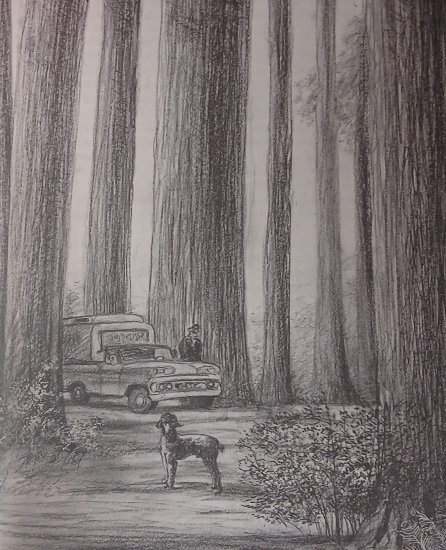

It is a very uneven travelogue anyway, by page 160 of the Folio Society edition I have we are in Seattle having left New York State and travelled along the US/Canadian border, so just one side of the rough rectangle planned for the journey. On that basis we should be looking at a four or five hundred page epic but instead it is only 241 pages in total, so over two thirds of the mileage is covered in a quarter of the pages and the detail in the first three quarters is lost in the remainder. That said I actually think the last quarter is the most important, as we have Steinbeck returning to search for his roots in California and finding that they are irretrievably lost. Cannery Row has been gentrified and he barely recognises the places of his childhood. Charley is also confused but that is mainly down to the visit to the giant redwoods which are so huge that he doesn’t seem to see them as trees and finds a small bush to mark instead.

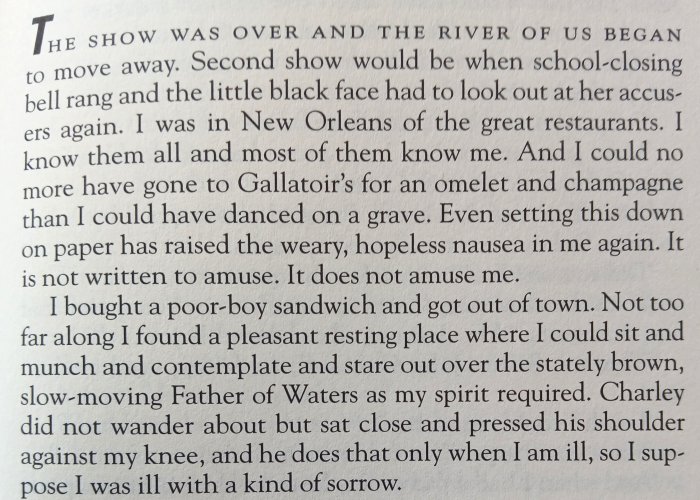

But it is pretty well the last section that is the most important of this ‘almost’ documentary and drives home Steinbeck’s dislike of some of what he found on his journey when he goes to New Orleans in search of ‘the Cheerleaders’. These frankly repellent middle aged white women gathered each day to scream abuse at six or seven year old children going or leaving school who just happened to be a different colour than they were. Steinbeck was appalled by them and the crowds they pulled together which meant the children needed police support just to go to school.

I’m going to leave it there.