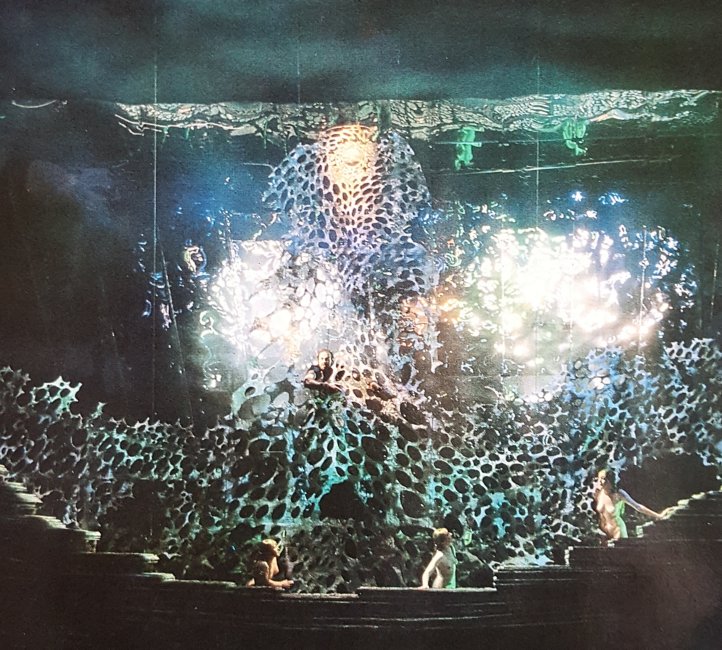

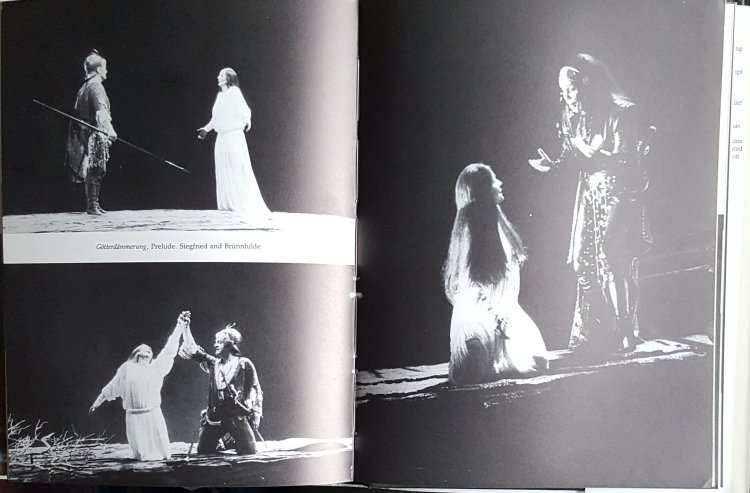

Back in March 2021 I reviewed a book about the trials and tribulations of staging the magnificent four opera series of the Ring Cycle by Richard Wagner, see here. Soon after that I purchased this magnificent cloth bound volume from The Folio Society, which is the full libretto in parallel text with Wagner’s original German alongside the superb translation by Stewart Spencer. This was first published by Thames and Hudson back in 1993 as ‘Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung; A Companion’, but the Folio version, published in 2020, is much larger at 289 × 205 × 41 mm, and has added illustrations by John Vernon Lord. As can be imagined as the four operas in the 1991 Barenboim recording I have play for a grand total of 15 hours and 5 minutes the libretto runs for well over three hundred pages with an extra seventy pages of authoritative essays on the development of the opera cycle at the beginning along with extensive notes at the end making a total of over four hundred pages of text with seventeen unnumbered leaves of plates. All in all a comprehensive guide to this greatest of Wagner’s operatic works. It should be pointed out that whilst the words sung are all in both languages the stage directions are only in English, this didn’t bother me but if you were looking for a ‘full’ parallel text then bear in mind that these parts are missing.

Wagner is unusual in writing his own libretto, it is much more common to either set an existing work or work with a librettist. For the most part he combined Norse with Old German mythologies in developing his story, these are closely related anyway with much the same characters only with different names, Odin becomes Wotan and Thor becomes Donner for example, but there are also echoes of the ancient Greek especially Homer’s Iliad. Occasionally he merges two characters from different origins into one such as Freia (this is how Wagner spells her name, more usually Freya or Freyja) a Norse goddess of fertility and in this version also the one who looks after the golden apples that confer everlasting life to the gods; she is also referred to as Holde, a similar but different character from German folk tales. Wagner also adds to the mythology with his own concepts such as carving important contracts in runes on Wotan’s staff, the staff exists in the mythologies but not the binding contracts. This melding of the various myths and new ideas make the reading of the libretto so fascinating, especially if you have a reasonable knowledge of the original mythologies, and whilst I have picked up some of this whilst listening to the operas it was only when reading the text at my own pace rather than moving rapidly on as you do in a performance that I more deeply appreciated the complex weaving of stories that Wagner achieved. Certainly the librettos can be read as a long poem without any deeper knowledge of the operas but I found myself adding the music in my mind as I read the words especially in parts I knew well.

The book is really lovely to read, as can be seen above in this section of the third opera ‘Siegfried’ shown with an engraving of the sword Northung being repaired by Siegfried. The sword had belonged to his father Siegmund but was shattered by Wotan during Siegmund’s fight with Hunding in the previous opera ‘Die Walkure’ (The Valkyrie) as Wotan’s wife, Fricka, had demanded that he die as punishment for his incestuous relationship with his sister Sieglinde which had left her pregnant with Siegfried. The illustrations deliberately do not include any of the characters but are rather of important objects within the opera cycle, which I think is an interesting choice as John Vernon Lord explains in his note on the illustrations:

I thought that the words and music together would be best for conveying the ‘appearance’ of the various characters. At the outset, I felt that the inclusion of people would detract from the symbolic nature of what I wanted to express.

It is later in this opera, in fact in the final scene, that we get one of the few ‘humorous’ lines although this was not intended as such by Wagner but I always smile when we reach the ‘This is not a man’ line when Siegfried discovers and wakes the Valkyrie Brunnhilde from where she has been left in a magical trance by Wotan.

It should be realised that Siegfried has never seen a woman before, being brought up by Mime in a secluded location away from all others, but even so ‘Das ist kein Mann!’ is not Wagner’s finest hour.

I have really enjoyed having a deeper dive into the text of the operas and will have a much greater understanding the next time I listen to or watch them, being able to look back over previous sections to refresh my memory has proved to be well worth the cost of purchasing the book especially as it is such a fine edition.