This month marks the eightieth anniversary of the first books that became the Mentor imprint, which would grow to be a major factual book publisher in America. Stepping forward a couple of years we see in 1948 two new paperback imprints first appear in the USA, Signet and Mentor, at first sight these series closely resemble the UK Penguin main series and Pelicans with Signet largely being fiction and Mentor for the most part factual. This is due to them both growing out of the wartime Penguin books printed in America to avoid shipping across an increasingly dangerous Atlantic Ocean. In 1948 Penguin decided to pull out of American publishing and their assets were purchased by Victor Weybright and Kurt Enoch both of whom had been running Penguin Books Inc based in New York since 1942 when the American Penguins were launched . Enoch had previously been head of Albatross Books, so knew how to run a publishing business, and was already in New York, having escaped Nazi Germany in 1940, whilst Weybright had been recruited by the owner of Penguin Books, Allen Lane, from the US Office of War Information back in London and returned to America to help Enoch. The two men formed New American Library of World Literature (NAL) in 1948 when they bought the American Penguin operation, but crucially not the name, and gained, at least in theory, 164 titles to start Signet and 24 to get Mentor going. I’d like to concentrate on Mentor as this grew out of a far less well known series in America which had taken the name of its UK equivalent, Pelican and which began eighty years ago this month in January 1946. The full list of titles, with their first published dates, as at the time of the takeover were:

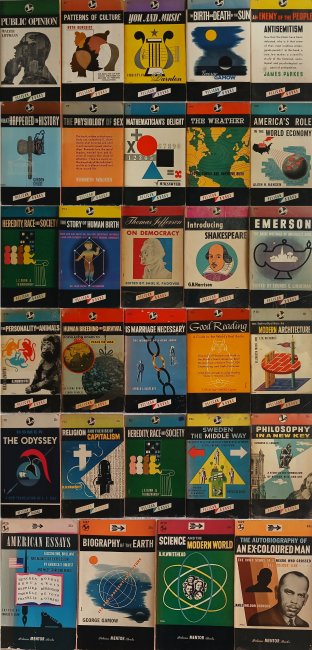

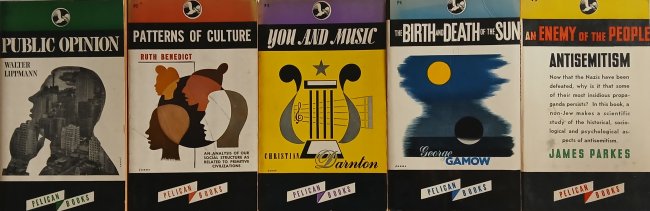

- P1 Public Opinion by Walter Lippmann – January 1946

- P2 Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict – January 1946

- P3 You and Music by Christian Darnton – January 1946

- P4 The Birth and the Death of the Sun by George Gamow – January 1946

- P5 An Enemy of the People: Anti Semitism by James Parkes – March 1946

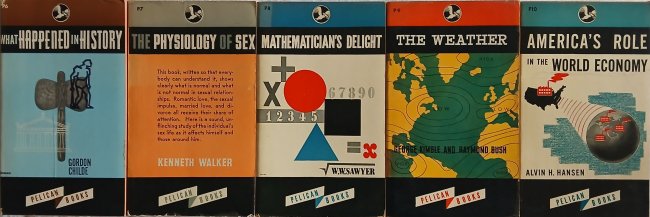

- P6 What Happened in History by Gordon V Childe – March 1946

- P7 The Physiology of Sex by Kenneth Walker – March 1946

- P8 Mathematician’s Delight by W.W. Sawyer – March 1946

- P9 The Weather by George Kimble and Raymond Bush – May 1946

- P10 America’s Role on the World Economy by Alvin H Hansen – April 1946

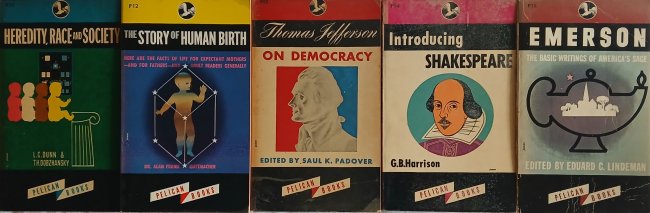

- P11 Heredity, Race and Society by Theodosius Dobzhansky and L.C. Dunn – November 1946

- P12 The Story of Human Birth by Alan F Guttmacher – January 1947

- P13 Thomas Jefferson on Democracy edited by Edward C Linderman – January 1947

- P14 Introducing Shakespeare by G.B. Harrison – February 1947

- P15 Emerson – The Basic Writings of America’s Sage edited by Eduard C Lindeman – March 1947

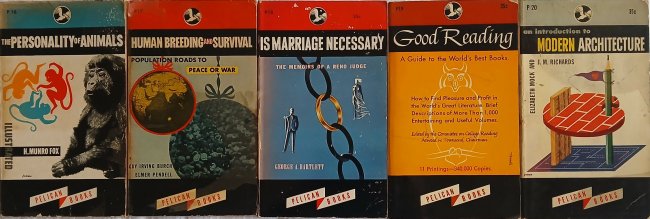

- P16 The Personality of Animals by H Munro Fox – April 1947

- P17 Human Breeding and Survival by Gut I Burch and Elmer Pendell – June 1947

- P18 Is Marriage Necessary? By George H Bartlett – July 1947

- P19 Good Reading edited by The Committee On College Reading – September 1947

- P20 An Introduction to Modern Architecture by E.B. Mock and J.M. Richards – September 1947

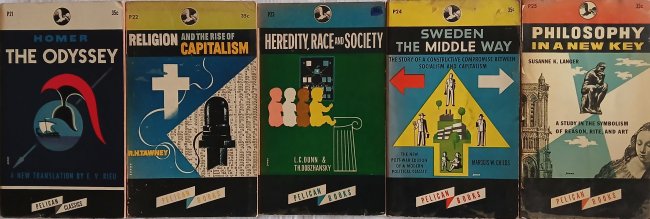

- P21 The Odyssey by Homer – trans E.V. Rieu – October 1947

- P22 Religion and the Rise of Capitalism by R.H. Tawney – November 1947

- P23 Heredity, Race and Society by Theodosius Dobzhansky and L.C. Dunn – November 1947

- P24 Sweden: The Middle Way by Marquis W Childs – January 1948

- P25 Philosophy in a New Key by Susanne K Langer, – February 1948

It’s an interesting mix of subjects, much like the UK originals. I said earlier that there were 24 titles to form the basis of Mentor yet the list above has 25 books, however careful checking will reveal that P11 and P23 are in fact the same book issued a year apart, yet inside both claim to be the first time this title was published. It is almost as if the publishers had forgotten they had already printed this book in 1946 so simply did it again exactly a year later in 1947. Of the twenty four titles ten had been originally printed in the UK, mainly as Pelicans, whilst the remaining fourteen were originals to the American Pelican imprint, the ten reissues are as follows:

- P3 – Originally UK Pelican A68 – July 1940

- P5 – Originally UK main series 521 – August 1945

- P6 – Originally UK Forces Book Club – November 1942 then Pelican A108 – December 1942

- P7 – Originally UK Pelican A71 – July 1942

- P8 – Originally UK Forces Book Club – April 1943 then Pelican A121 – August 1943

- P9 – Originally UK Forces Book Club – September 1943 then Pelican A124 – November 1943

- P14 – Originally UK Pelican A43 – May 1939

- P16 – Originally UK Pelican A78 – December 1940

- P21 – Originally UK Services Edition SE18 – 1945 then Classic L1 – January 1946

- P22 – Originally UK Pelican A23 – February 1938

Bizarrely two of the above had also passed through the American Penguin numbering before reappearing as American Pelicans, P7 had already been 507 (1942) but this change seems highly sensible as it is not a work of fiction, whilst P21 had first appeared in the USA as 613 (November 1946). Quite why The Odyssey moved from the fiction main series to the factual Pelicans, becoming by the way the only American Pelican Classic almost twenty years before the UK business came up with this series name is a mystery as it seems to make no sense. After 1948 the rights to the EV Rieu translation of The Odyssey were not part of the transfer of intellectual property so when Mentor came to reprint the now renumbered M21 they used a different translator, W H D Rouse, where it became the first Mentor Classic and went through 47 reprints by 1976 including at least one renumbering ending up as ME2519. All the other P series Pelicans were simply reprinted unchanged apart from the P becoming an M for Mentor although later on Mentor introduced sub categories so for example P13 ‘Thomas Jefferson on Democracy’ became M13 when first reprinted and then this was later changed to MD13.

The first four books published as Mentor from March 1948 were actually initially indicated on the cover as Pelican Mentor to help inform the general public regarding the change of name before dropping the Pelican part when they came to be reprinted. Enoch and Waybright also did this with the much more prolific main series as it morphed into Signet only in this case seventeen new books and a small number of reprints bore the imprint of Penguin Signet for a few months. I haven’t yet found any evidence of reprinted American Pelican titles being listed as Pelican Mentor, only the four new books appear to have had that designation. It is worth noting that the few books originally published as Penguin but reprinted as Penguin Signet and then later simply as Signet, which include 615 Lady into Fox, command far higher prices as the Penguin Signet reprint version than as either the Penguin or Signet versions alone. The four Pelican Mentor titles are:

- M26 American Essays by Charles B Shaw – March 1948

- M27 Biography of the Earth by George Gamow – April 1948

- M28 Science and the Modern World by A.N. Whitehead – May 1948

- M29 The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by J.W. Johnson – June 1948

As can be seen the covers feature bold designs, so much more enticing to their target American audience than the simple blue and white that would be the trademark of the UK Pelicans for decades. It was the use of full colour laminated covers, especially on the main series, that would be one of the primary falling out points between Penguin Books Inc in the USA and Allen Lane back in the UK, where typographic covers would reign supreme as the Penguin identity for many years to come. Although it was almost certainly tax difficulties between the two countries that ultimately prompted the split in the end.

Interestingly New American Library was bought out and became part of Penguin Publishing Company in 1987 neatly bringing the whole enterprise full circle. But confusingly there is also an Irish publishing company that calls itself Mentor Books which started in 1979 and specialises in educational works but has nothing to do with the American company which predates them by thirty one years and was well established by the time the Irish firm started