The start of the trial of Hadi Matar on the 10th February 2025 for the attempted murder of Salman Rushdie in August 2022 prompted me to go back to the shelf of Penguin Drop Caps volumes far earlier than I planned, as I knew that there I would find Haroun and the Sea of Stories. This novel for children was Rushdie’s first published work after ‘The Satanic Verses’, which had led to the fatwa declared against him by Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran for blasphemy and which almost certainly inspired Matar, a twenty seven year old American of Lebanese descent, to attack Rushdie almost killing him, stabbing him fifteen times, leaving him blind in his right eye, with a severely damaged hand and multiple other injuries. That the novel was published ten years before Matar was born and that Iran had said the fatwa would not be enforced also before he was born seems not to have affected Matar who admitted he had only read a few pages; and Rushdie had said that he was at last leading a relatively normal life without protection in an interview just two weeks before the attack. Still enough of the context as to why I picked the book up, let’s look at this wonderful fantastical story which I hadn’t read before.

Rushdie had me hooked from the opening lines of this novel:

There was once in the country of Alifbey, a sad city, the saddest of cities, a city so ruinously sad that it had forgotten its name. It stood by a mournful sea full of glumfish which were so miserable to eat that they made people belch with melancholy even though the skies were blue.

In the north of the city stood mighty factories in which (so I’m told) sadness was actually manufactured, packaged and sent all over the world, which never seemed to get enough of it. Black smoke poured out of the chimneys of the sadness factories and hung over the city like bad news.

It goes on to say that most places in Alifbey had just one letter as their name so there is the town of G and the nearby valley of K nestled in the mountains of M, this means that lots of places had the same name and therefore post was often delivered to the wrong place. In a helpful couple of pages at the back of the book Rushdie explains that the name Alifbey is based on the Hindustani for alphabet and that another destination on the journey of our heroes, for what sort of children’s book doesn’t have heroes even unlikely ones, is The Dull Lake “which doesn’t exist, gets its name from The Dal Lake in Kashmir, which does”. Rushdie was born in India and lived there until he was seventeen and takes a lot of inspiration in his writing from his youth. I have mentioned our heroes and they are Rashid Khalifa and his son Haroun, these are named after Haroun al-Rashid the legendary Caliph of Baghdad who appears in the Arabian Nights stories. Rashid is the happiest man in the very sad city and is renowned as a storyteller gaining the titles of The Ocean of Notions or the Shah of Blah because he could keep telling tales without repeating himself, weaving stories together without ever losing the intricate plots and therefore whenever he spoke he would draw huge crowds. This made his especially popular with politicians trying to get people to listen to them as elections approach as he could start the rally and pull people together from the surrounding area.

But one day disaster struck, the flow of stories just stopped, Rashid couldn’t string two words together and this was at the start of a tour arranged by politicians so it was vital that the reason was discovered. The second night of the trip saw Rashid and Haroun on a boat on The Dull Lake where Haroun encounters Iff the Water Genie who had come to disconnect the invisible tap that linked Rashid to the Sea of Stories, the source of all his tales. In vain Haroun argued that it was a mistake but finally he convinced Iff to take him to the Earth’s invisible second moon, Kahani, so that he could meet the leader of the Eggheads and appeal for Rashid’s tap to be reconnected. Travelling on a giant mechanical Hoopoe called Butt they arrive on Kahani and find the Ocean of Stories is heavily polluted with the stories dying off so Haroun then has to find out what is causing the pollution and stop it. Along the way he finds Rashid has also made his way to Kahani and has his own quest to undertake.

The book is a wonderful adventure story full of linguistic jokes, like the talking fish with lots of mouths which are called the Plentymaw fish in the Sea and the Pages, or soldiers, arranged into chapters and volumes instead of companies and battalions. It is split into twelve chapters, each no longer than fifteen pages so ideal to be read as to a child as a bedtime story over a couple of weeks. I loved the book and it was so different to the other book by Salman Rushdie I reviewed on this blog back in 2019, The Jaguar Smile. I also have his second novel, Midnight’s Children, which was his first best seller, hopefully I won’t wait another five and half years before reading that.

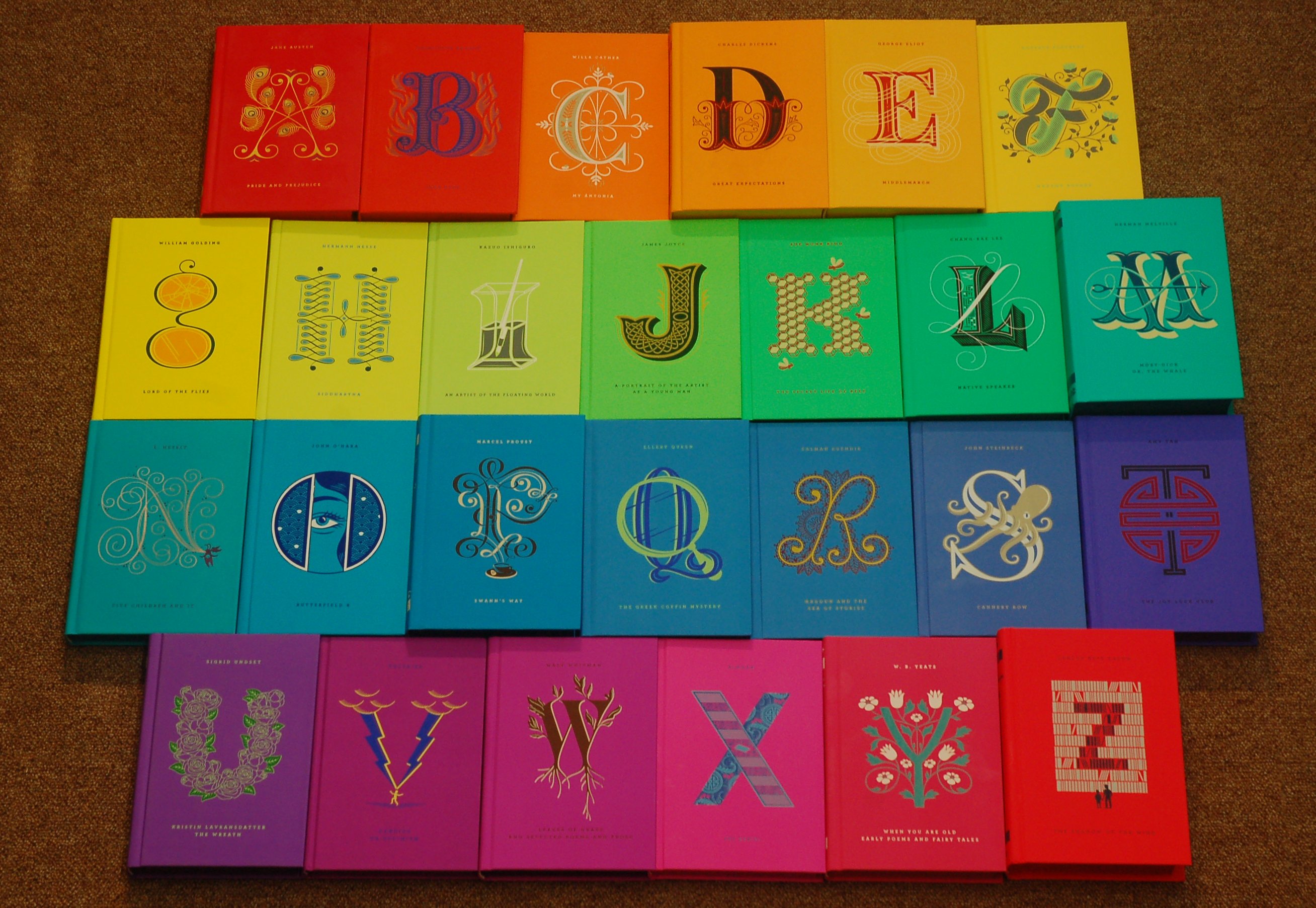

You can find more about the Penguin Drop Caps series in my overview here, which also includes links to the various books I have reviewed from this set of twenty six books.