This week I’m going to cover not one but five books, all of which started life as articles in Scientific American under the heading of Mathematical Games. This column was originated by Martin Gardner in 1956 and I first came across it in my school library in the early 1970’s and became hooked, looking forward to the next monthly issue, which fortunately the school subscribed to. Eventually Gardner compiled fourteen books based on the column, five of which I own.

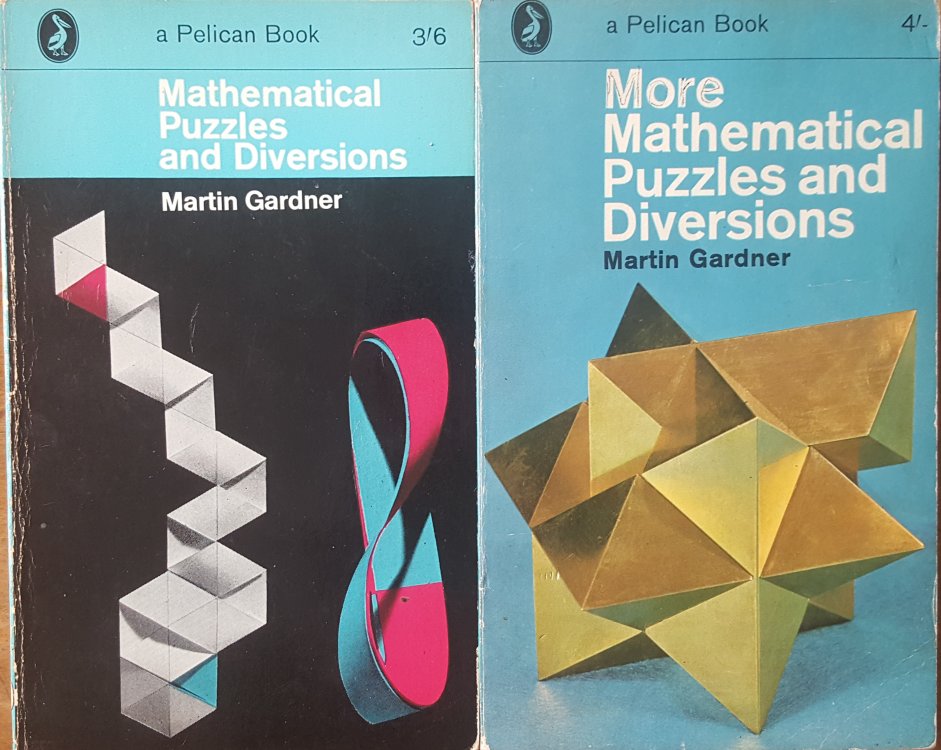

The first book has an unfolded flexagon alongside a mobius strip and immediately highlights the cover design issues with the Pelican editions in that although flexagons are the subject of the first chapter, the curious single-sided mobius strip is not referenced in this book. Flexagons were in fact the subject of the very first article Gardner wrote for Scientific American and are constructed by folding a strip of paper in a triangular pattern until you create a hexagon which when manipulated, or flexed, opens out and then returns to a hexagon shape but with different sides displayed. So if the user had coloured the original two visible sides these would disappear and new blank faces appear. It is possible to create flexagons with large numbers of faces but the number is always divisible by three. The book describes how to make a couple of different variations and I remember having great fun playing with them. Other chapters include the mathematical game of Hex, an overview of the puzzles created by American Sam Loyd, card tricks (Gardner was a keen magician as well as mathematics writer) and random collections of short puzzles which would be a staple of Mathematical Games columns and their successors in Scientific American.

The second book has a cover that is entirely from the imagination of the designer, in this case Denise York, as it has nothing to do with anything in the book which does however have an article about the five platonic solids one of which this definitely isn’t. Again we have an article about a great historical puzzle maker in this case the English near contemporary of Sam Loyd, Henry Ernest Dudeney, there are also discussions of three dimensional tangrams, magic squares, recreational topology and even origami. Like all the books I have each chapter is reprinted in the book and an addendum is added covering items that were raised after the publication of each column, sometimes pointing out things that were incorrect. Gardner surprisingly wasn’t a mathematician, or an academic, he was just fascinated by mathematical puzzles. Two of the people that continued the mathematics column in Scientific American after he retired in 1979 were professors Douglas Hafstadter and Ian Stewart.

The first two books were published by Pelican in the mid 1960’s but the next time they printed one of Gardner’s books was another pair, this time in 1977 and 1978. Again the the covers are not relevant to the text with the ancient puzzle of the Tower of Hanoi on the cover of Further Mathematical Diversions although this was in fact covered in the first book ‘Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions’ but this third Pelican title does have some of my favourite columns in it starting with the paradox of the unexpected hanging where the judge pronounces on the Saturday of the judgement that:

The hanging will take place at noon, on of of the seven days of next week but you will not know which day it is until you are informed on the morning of the day of the hanging.

The prisoner is despondent but his lawyer is pleased as he reasons that the sentence cannot be carried out because he cannot be executed on the Saturday as that is the last possible day and therefore he would know on the Friday that he was to be executed that day. Likewise it can’t be the Friday as Saturday is impossible so Friday is the last day and so on working back through the week. The logic is fine and worked right up until Thursday when the man was unexpectedly hung. The discussion on why the logic fails is quite entertaining.

Also in this book are articles on the transcendental number e, the properties of rotations and reflections, gambling, chessboard problems and numerous other subjects including the inevitable sets of nine short problems, but my favourite, because it prompted me to attempt to build one was about a ‘computer’ built of matchboxes and beads which could ‘play’ noughts and crosses (ticktacktoe) in fact the original article that this chapter was based on first appeared in Penguin Science Survey, a publication I was unaware of at the time I first read this article. The machine is more of a simple learning machine than a true computer but using three hundred matchboxes it is possible to have something that gradually optimises how to play the game and in the example described it was winning, or at least not losing the majority of games after just twenty goes.

The fourth book again doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the cover illustration but does have various articles including Pascal’s Triangle, infinities that are bigger than other infinities, the art of Dutch artist M.C. Escher, random numbers and a ‘simple’ proof that it is impossible to trisect an angle using just a compass and ruler although bisection is extremely easy. There are again many other subjects covered although unlike the other volumes there isn’t a chapter of nine short puzzles. I remember being fascinated by aleph-null and aleph-one infinities when I first read this piece as a teenager, the concept of ‘countable’ and ‘uncountable’ series resulting in differing ‘sizes’ of infinities was so different to what I was being taught in mathematics at the time that I needed to read it a couple of times to get my head around what was being explained and I have of course come to love the art of M.C. Escher.

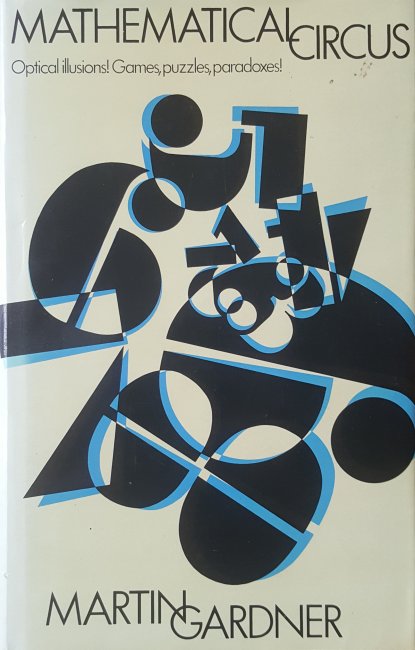

The final book I have by Gardner is a hardback published by Allen Lane rather than paperback Pelicans although both are imprints of Penguin Books. It follows much the same format as the other four with twenty chapters based on articles from Scientific American but this time I don’t remember reading many of these before but topics include such diverse subjects as Fibonacci and cyclic numbers, the Turing test, devised by Alan Turing to determine if a machine could fool a human into believing they were conversing with another human. The smallest cyclic number is one that I have always remembered and it is 142,857, what makes it cyclic well just multiply it by 1 to 6 and see that the digits remain in the same order just starting from a different place i.e.

- 142857 x 1 = 142857

- 142857 x 2 = 285714

- 142857 x 3 = 428571

- 142857 x 4 = 571428

- 142857 x 5 = 714285

- 142857 x 6 = 857142

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the mental workout reading these books again this week and remembering oddities of mathematics that have stuck with me since my teenage years and if you have any liking for puzzles I heartily recommend searching out Martin Gardner’s extensive output.