If Margery Sharp is known at all nowadays it is of the creator of The Rescuers in a series of nine children’s books started in 1959, although a lot of people familiar with the two Disney animations of her stories about heroic mice may well not even know of the original books. The Nutmeg Tree precedes these by over twenty years, being first published in 1937 when Sharp was a well known author of novels for adults and this one is a romantic comedy. The story starts with the rather surreal position of Julia singing in her bath but without the usual reverberations, as it turns out that she is sharing the bathroom with most of her movable furniture, up to and including a grandfather clock, so she is somewhat disappointed with the acoustics. Now the reason she is in there with the furniture, and intends to be there for some time, is that bailiffs are in the living room, the other side of the door, and are looking for items to seize that could be sold to recover the money she owes as she is completely broke. Julia ultimately persuades the bailiffs to fetch the man running the pawnbrokers down the street and agrees to sell him the furniture in the bathroom sight unseen leaving her with a few pounds after clearing her debts. She needs the money as she has had a letter from her daughter, Susan, whom she hasn’t seen for years and is now living in France with her grandmother inviting her over in order to hopefully approve of her choice of husband.

Julia’s own first husband, and the father of Susan, had been killed during the first world war and after Susan was born they both lived with his parents for a while until the call of the stage and her old life drew Julia back to London and away from the frankly dull country life she was living. She left Susan with her grandparents as she would undoubtedly have a much better life with them as they were quite rich. They gave her the enormous sum of £7,000 in government stock (around £400,000 in today’s money) to set herself up as an independent woman and her first task on arriving in France is not to let on that she had frittered it away. Her various adventures in trying to hide the fact that she is now penniless and the interactions with Susan, Mrs Packett and Bryan (Susan’s intended) are where most of the comedic elements ensue as Julia recognises in Bryan a bit of herself and therefore is determined that he is not suitable for Susan. To add to the general confusion Julia had met a troupe of trapeze artists on the boat over to France and the senior brother had rather fallen for Julia and had asked her to marry him so was writing to her and then ultimately arriving at the house in France so she needed to explain him as well.

The book was adapted into a play in 1940 and then a film in 1948, which changed the title to Julia Misbehaves and altered the story quite a lot. The film starred Greer Garson as Julia and Walter Pidgeon as her now separated rather than dead husband and the young Elizabeth Taylor (aged 16) as Susan.

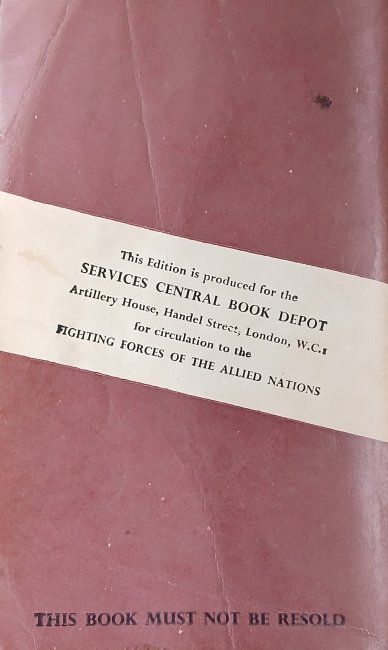

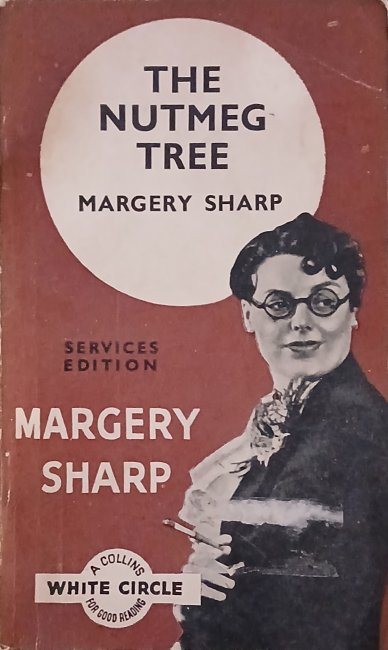

This edition was published by Collins in 1946 with a portrait of Margery Sharp on the cover as part of their short lived White Circle paperback range and is particularly notable as it is from the roughly 160 titles in this series also published as a Services Edition as explained on the rear cover, below. Most of the paperback printers during WWII printed Services Editions of books in their normal range, partly for patriotic reasons but also because doing so gave them access to more paper which was in short supply. None of them could be resold and should, in theory, be returned to the central book depot or passed on amongst the troops, as a consequence Services Editions are much sought after by collectors and when they are found are usually in fairly poor condition.