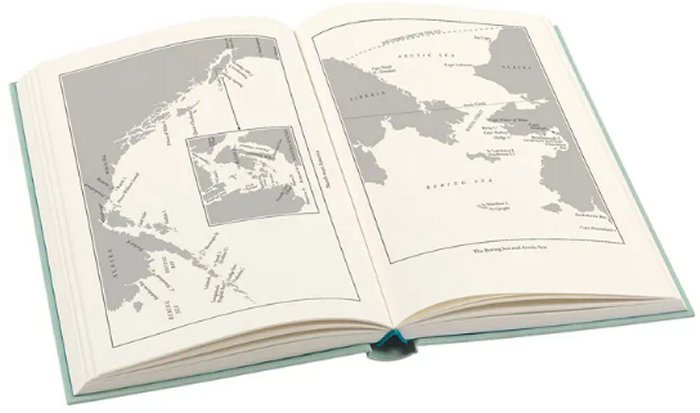

Before his third, and final, voyage Cook was formally given the rank of Captain and was officially retired, assigned to Greenwich Hospital at the age of just forty seven. He accepted this transfer off active duty on the basis that he would be allowed to come back and this he duly did, taking command of the apparently refurbished HMS Resolution in 1776. This time he was tasked to head north in search of the fabled North-West Passage which would give a route above the top of Canada between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. This had been sought for many years starting from the north Atlantic, Cook’s instructions was to start off Alaska and see if the route could be discovered coming in the opposite direction. Charts at the time for this part of the world were poor to say the least with one of the maps showing Alaska as a giant island off the coast of Canada although the Danish explorer Vitus Bering had discovered the Strait that bears his name many decades earlier whilst in the employ of the Russian navy.

In the absence of any alternative route Cook headed south to go north as he first had to enter the Pacific. The first thing that strikes the reader as we head back to familiar territory of New Zealand, Tonga and Tahiti is that the book is written in a very different style compared to the first two voyages. Instead of the formal naval journal with each day detailed with position, wind speed, heading etc. we get a manuscript that is far more aimed at the lay reader where a lot of the technical information is dispensed with and it reads much more like a diary. I have checked this with the full 1784 first edition to make sure that this style is not just a creation of the abridgement and that book is also in this more readable style so Cook was clearly aiming at publication from the start. Sadly he was never to see the book come out as he was to die on this voyage and never return to England but the manuscript that was to be published was just 17 days behind when he died so he must have been constantly working on it whilst at sea.

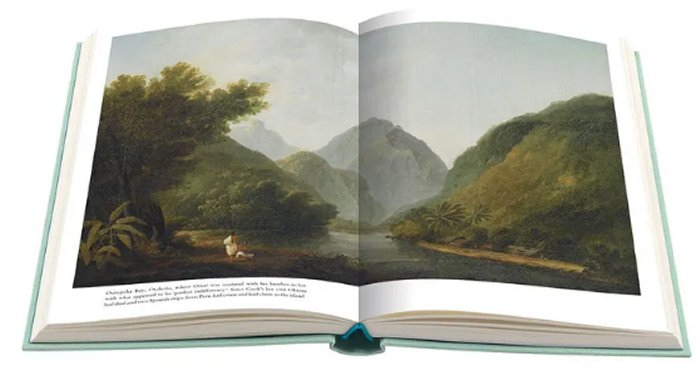

Cook had another reason to go to the South Pacific and that was to return Omai, a native of one of the islands with Tahiti who had travelled back on HMS Adventure as part of Cook’s second voyage. Omai was the first Polynesian to visit Europe and had achieved celebrity status whilst he was there and his return was the publicly stated reason for the trip as the search for the North West Passage was kept secret. It took longer to get to the South Pacific than intended so Cook decided that by the time he headed north it would be too late to attempt the search so stayed in the southern summer before heading north the next year and on his way became the first European to encounter Hawaii, or the Sandwich Isles as he named them after the then First Lord of the Navy, Lord Sandwich. Cook’s two ships HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery, commanded by Captain Charles Clarke, arrived at an opportune time as the islanders believed that their god was due to arrive at pretty well the same time as Cook did so they were treated royally and the elaborate ceremonies are described in the journals. When he finally left to continue north he was somewhat later than the predicted date for the god’s departure and the islanders were getting a little annoyed that he had not gone according the the plan.

Cook then headed north sighting Oregon and then following the coast of Canada, all the way to the Bering Strait producing the first accurate maps he then went east across the top of Canada before being stopped by ice bu which time he had gone past 70 degrees north. Turning round he headed west and continued on that heading, mapping the Siberian coast of Russia before again being stopped and having to go back to the Bering Strait. By then it was September and nothing more could be done so far north so he decided to return to Hawaii where they had been so welcome. The ships stayed for a month and were again welcome but soon after leaving a mast broke and knowing nowhere else he could go to effect repairs Cook went back to Hawaii and this time he was definitely not expected, Lomo was supposed to appear then leave and not come back again so soon and relations between the islanders and the ship’s crew rapidly deteriorated leading to the killing of Cook.

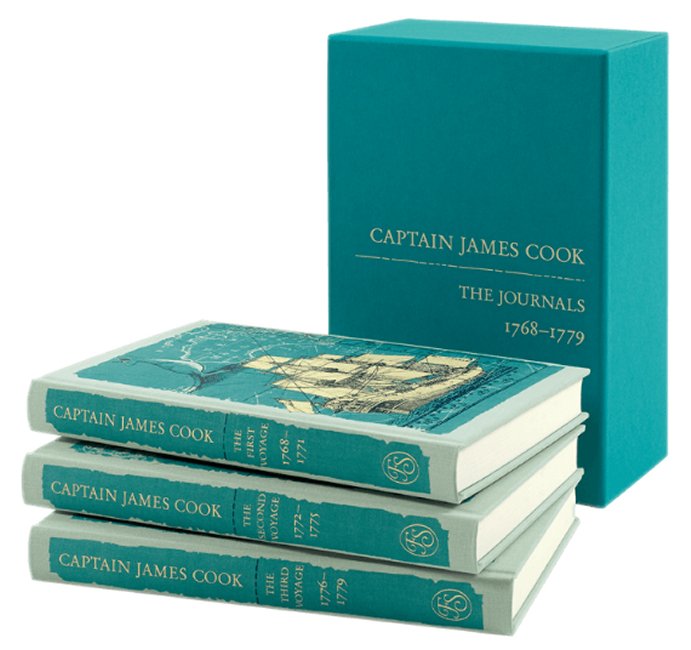

Now at this point the two versions of the book I have separate as the first edition is just two volumes in to a three volume set, the third volume being written by Captain King, whilst the Folio edition pretty well stops here presumably as the set is called the Journals of Captain Cook and he is now dead. The three books that make up the Folio set are however an excellent summary of what should in fact be a much larger nine volume set if you had the full version but it is no less good for that. Anyone interested in voyages of exploration should definitely read Cook and this is one of the most approachable editions being beautifully typeset and therefore a pleasure to read. One oddity of the images that I have used from the Folio Society web site is seen below as the picture of the included maps appears to show them in the middle of the book whilst they are in fact at the front of each volume.