I have recently managed to complete my collection of these sixteen children’s books, most of which were printed in 1947 in cooperation between Penguin Books in England and Fernand Nathan in France. The last two titles VC15 and VC16 are translations of books that originally came out in England in December 1947 and August 1948 respectively so presumably the French versions were later. After the war Penguin were keen to restart their international publications and came up with the plan of altering the text for a small number of Puffin Picture Books into French and printing them in England to avoid having to ship the lithographic plates abroad. This would still require a considerable amount of work to blank out the existing English text and replace it with a translation as the whole page is printed as one unit. This would therefore have been difficult enough but there were also some illustrations altered, some of which were done for obvious reasons others are more obscure.

The books were printed in editions of 20,000 copies per book and none appear to have been reprinted. In the intervening, almost eighty, years this relatively small production number along with the fragility of books consisting of eight folded sheets stapled down the centre making a thirty two page book meant that few have survived to the present day. Although they are a reasonably practical series of children’s books to collect and it has only taken me around five or six years to accumulate them all mainly from French second hand book dealers online. Interestingly none of the books mention who did the translation, presumably somebody at Fernand Nathan, or who made the alterations to the pictures, possibly the original artists. It is also somewhat ironic that the French translations were created, as one of the original inspirations for the Puffin Picture Book series was the French series ‘Albums du Pere Castor’.

I am indebted to the Penguin Collectors Society for their invaluable Checklist of Puffin Picture Books which includes a full listing of these books so that I could check each one as I obtained it, and the checklist is the source of a lot of the information in this blog. Whilst this book lists most of the differences between the English and French illustrations it doesn’t show the variations, so below I will do so as I think it is interesting to see just what cultural differences were picked up in the changes. Firstly let’s list the seven books where it is simply a text translation difference and as you will quickly spot there are several obvious title changes:

- VC2 – Les Animaux de notre hémisphère – originally PP7 Animals of the Countryside

- VC5 – Vacances a la Campagne – originally PP33 Country Holiday

- VC7 – Les Abres de mon pays – originally PP31 Trees in Britain

- VC9 – Merveilles de la Vie Animale – originally PP44 Wonders of Animal Life

- VC10 – Comment Vivent les Plantes – originally PP58 The Story of Plant Life

- VC13 – Les Chiens – originally PP56 Dogs

- VC16 – La Péche et les Poissons – originally PP53 Fish and Fishing

Now let’s look at the ones with illustration changes which will also give you a chance to see how lovely this series of books are, either in the original 119 titles in English or these 16 in French:

VC1 – Les Oiseaux du village – originally PP20 Birds of the Village

This one is a mistake rather than a deliberate change, but page eight has a number of birds each identified in the adjacent text by a number. However in the French version the numbers within the illustration have been removed which makes the text meaningless. The alteration is omitted from the checklist which regards this book as a translation only.

VC3 – Les Insectes – originally PP5 A Book of Insects

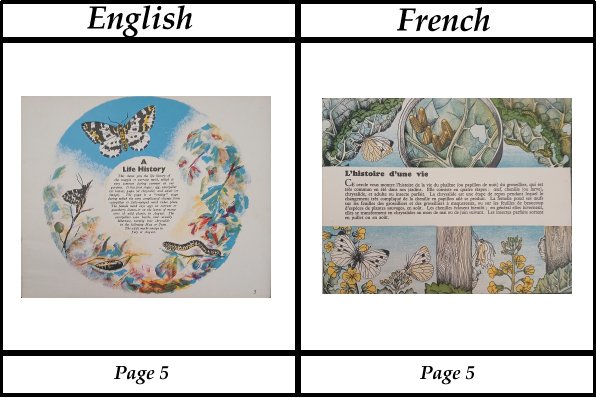

Two pages within this book are completely changed with totally new designs. The first one makes sense to change as the French text appears to be significantly longer than the English and therefore difficult to fit into the circular gap. The second one is less obvious why it was altered to a much more scientific form.

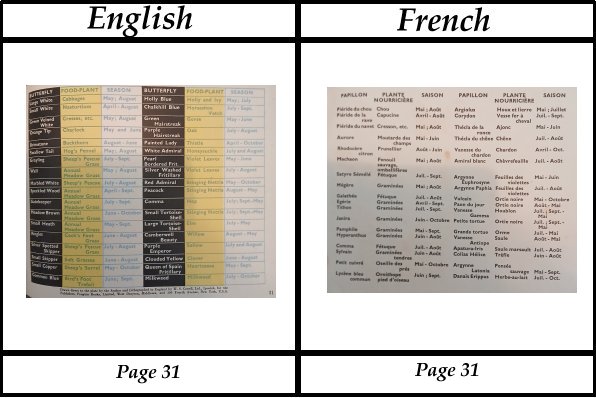

VC4 – Jolis Papillons – originally PP29 Butterflies in Britain

The change for this book is perfectly understandable as it is simply the table on the last page and changing all the text and replicating the original format is probably unnecessary. The deformation of the left hand side of the English text is simply because I didn’t want to force the page flat and possibly loosen the staples. This lack of formatting is not mentioned in the checklist which again regards this book as a translation only.

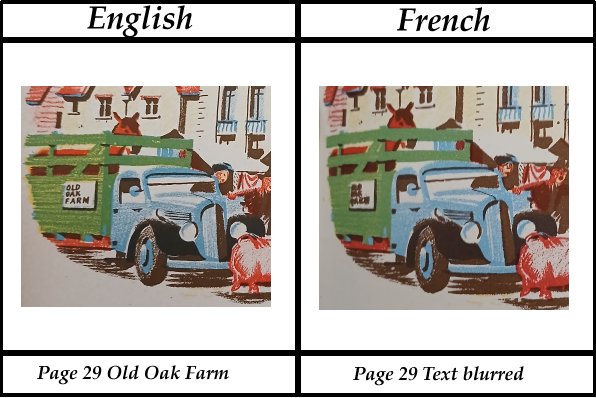

VC6 – A la Ferme – originally PP4 On the Farm

The biggest difference before the two versions is on the first page where the British farmer is replaced by a man more obviously at work.

The other change is not included in the checklist and it is the amendment to the sign on the side of the lorry on the page dealing with going to the market, where the English text has simply been blurred out.

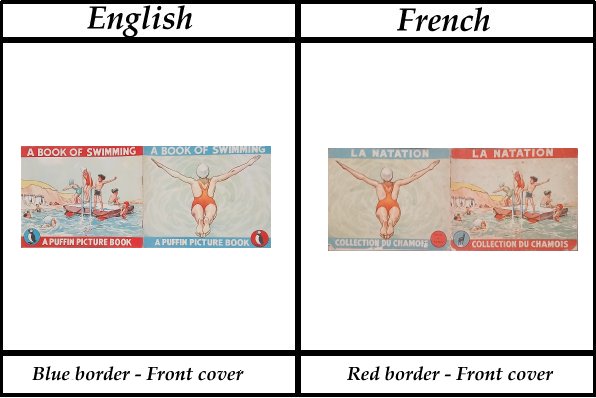

VC8 – La Natation – originally PP48 A Book of Swimming

Strangely this change isn’t in the checklist either although it is a pretty significant alteration, with the front and rear covers being transposed.

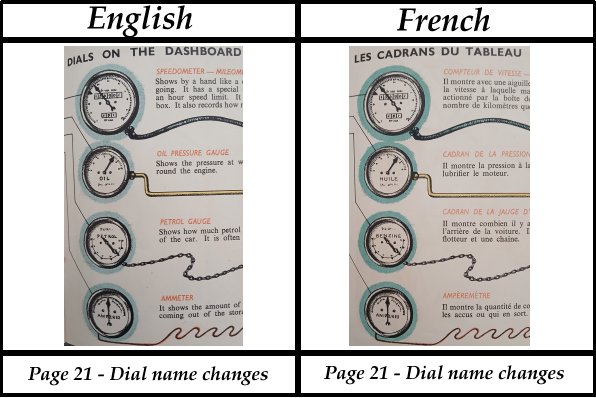

VC11 – L’Auto et son Moteur – originally PP38 About a Motor Car

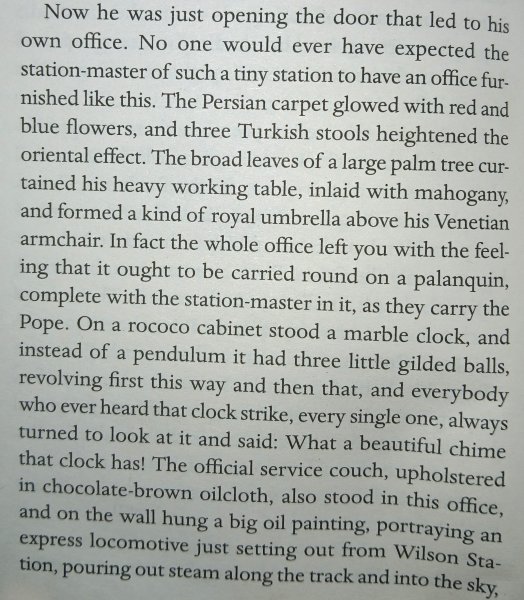

The two small changes to this book are so small that they were ignored by the checklist, the first one is quite amusing and is a text alteration on the middle page spread where in the English version after the word chassis it points out that this is a French word, quite rightly the French edition doesn’t bother with this explanation. The other change is shown below and is an amendment to the text on the gauges.

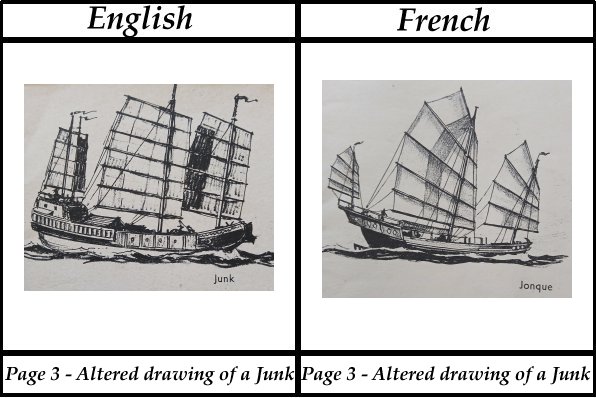

VC12 – Les Bateaux – originally PP11 A Book of Ships

Now we get to the book with the most changes between the two versions, all of which are included in the checklist and we start on page three with a new drawing of a Chinese Junk.

The very next page has the British naval flag, the Red Ensign, altered to be unrecognisable in the French version. This also occurs on page 24 but I’ve just included the one example here.

Next comes a change of headgear between two sailors

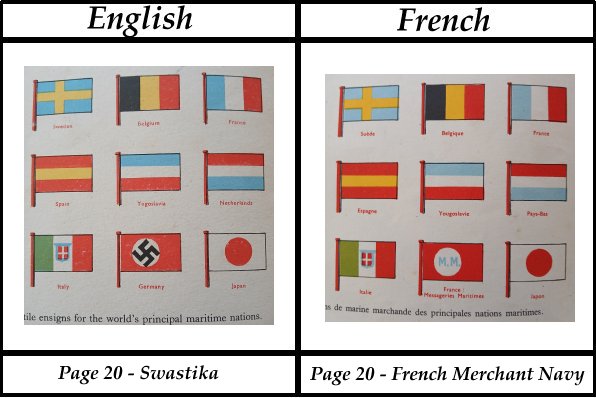

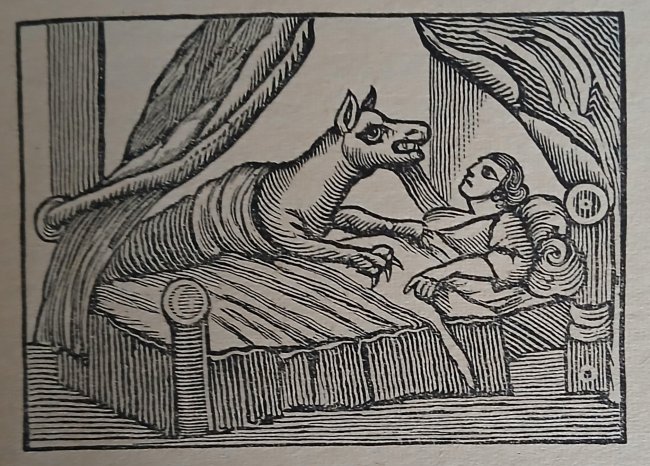

We then get a change that needed to be made from the original British edition, which was printed in June 1942, when the German flag would logically appear, to 1947 when it wouldn’t, or at least not in that form. The British book would be completely redesigned when it was reprinted in 1952 and no swastikas appear in that either.

Finally we come to page 27 where the illustration at the top of the page is reversed and indeed looks like it was completely redrawn.

VC14 – Les Merveilles du Charbon – originally PP49 The Magic of Coal

With this book only the front cover is amended to change both the helmet, the French version is more rounded and doesn’t have a lamp, and also the miner’s tattoo on his chest. This goes from St George and the dragon on the British miner to the symbol of France, the Gallic Rooster, in the French version. Whilst compiling this list I also realised for the first time that this book is slightly, but noticeably, larger than most of the other Puffin Picture Books or indeed the Vieux Chamois.

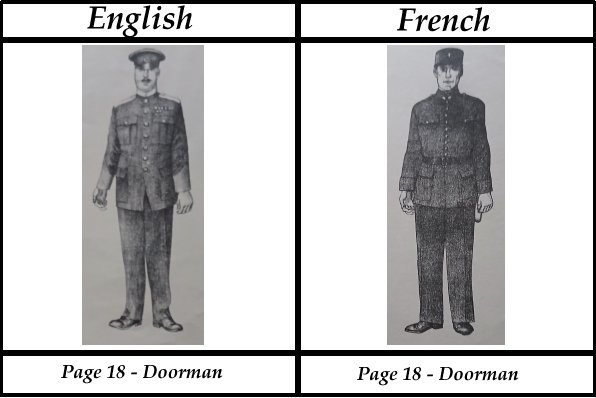

VC15 – Le Théatre – originally PP75 The Theatre at Work

The final set of changes involve a couple of uniforms at the theatre both of which are in the checklist, firstly the doorman.

and finally the fireman who looks more prepared for disaster in the French version

That brings us to an end of this overview of the Vieux Chamois series, I’d love to know why they were called Old Chamois but I doubt that I’ll ever find out.