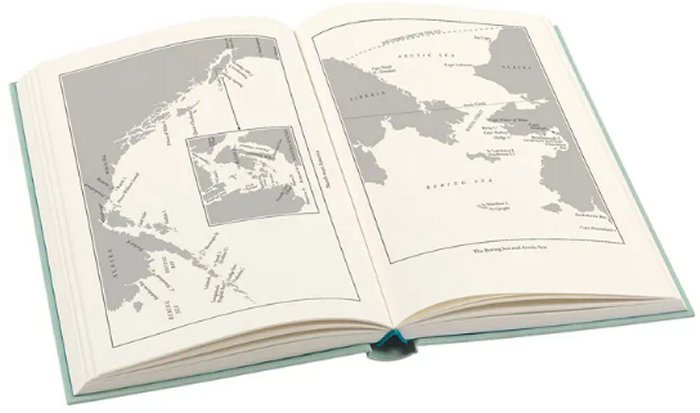

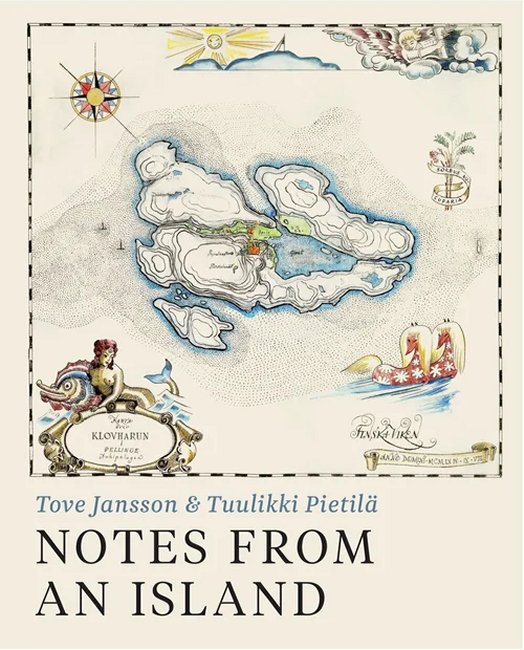

For twenty six summers from their late forties until their early seventies Tove and her life partner Tuulikki retreated to the small island of Klovharun in the Gulf of Finland where they could escape from city life and work and relax in relative peace and quiet. This book tells the story of the building of their cabin and some aspects of their life on the island with extracts from Tove Jansson’s diary, log entries from Brunström, a fisherman who with a couple of colleagues did most of the actual construction of the cabin including the dynamiting of a huge boulder out of the way, and of course Tuulikki Pietilä’s (Tooti) beautiful aquatints mainly done in the 1970’s. Originally published in 1996 in Swedish this is the first English translation, published by Sort Of Books in 2021. The lovely cover is a map of the island drawn by Tove’s mother Signe Hammarsten Jansson (Ham) who was a frequent visitor well into her eighties and was the inspiration for Moominmamma. Tooti was also to be immortalised in Jansson’s Moomin books as Too-Ticky; who has a lot of the characteristics of the real Tooti including practicality and a love of the sea.

This short book is an absolute delight, the first section deals with the decision of Tove and Tooti to seek another island as their own hideaway after Tove had shared the family retreat on the island of Bredskär with her parents, brother and eventually her niece. The construction of a cabin was done without formal permission as Brunström had pointed out that getting agreement from everyone who could be involved would almost certainly never happen but if they just built it and then asked the fait-accompli would probably just get passed, and so it turned out. Building on such a remote skerry which up until then had only been home to seabirds proved to be difficult and there are numerous log entries where Brunström (his first name is never given) couldn’t get materials out to the island due to the bad weather and high seas. Life on the island is covered more deeply in Tove’s work for adults, especially her best known ‘The Summer Book’, where Brunström is renamed Eriksson, but this is, as the title suggests, ‘Notes from an Island’ rather than the complete stories, with a blend of fiction and fact, found in the more famous book.

Tove introduces herself as a lover of rocks as is fitting for a sculptor’s daughter and many a tale is told of moving stones from one place to another throughout a summer to improve some aspect of the island only to find, when returning the next year, that everything had simply been moved back by the sea. Tooti is the daughter of a carpenter and her love is wood so maintaining the jetty and boat fell to her with less good wood being chopped up by Tove as firewood and the best pieces that floated by the island being saved for use in Tooti’s art. She was also more practical especially with the generator they would take a day coaxing into life or the temperamental propane fired refrigerator which was mainly used to store fish to feed their cat. Tove was also determined to have flowers growing on the island and cleared a small meadow for sea grass and also looked after that most Finnish of home features the rowan tree against one corner of the cabin.

I’ll close with a small section covering the time that Tove and Tooti made it out to the island before the surrounding ice broke up which will give a flavour of the narrative and the sheer joy these two ladies took in each others company:

The cabin had that closed in chill that Brunström would have called “cold as a wolf’s parlour”, and someone had burned all the firewood. We found a couple of wooden crates in the cellar and got them to burn and dragged in the sawhorse and some ice-covered timbers to thaw.

We were exhilarated by change and expectation and ran headlong here and there in the snow and threw snowballs at the navigation marker. Tooti made a toboggan out of thin strips of wood and we rode it again and again from the top of the island far out across the ice.

When we tired of that game, we sat down and took stock. The sea was chalk white in every direction as far as the eye could see. It was only then that we noticed the absolute silence.

And that we had started whispering.