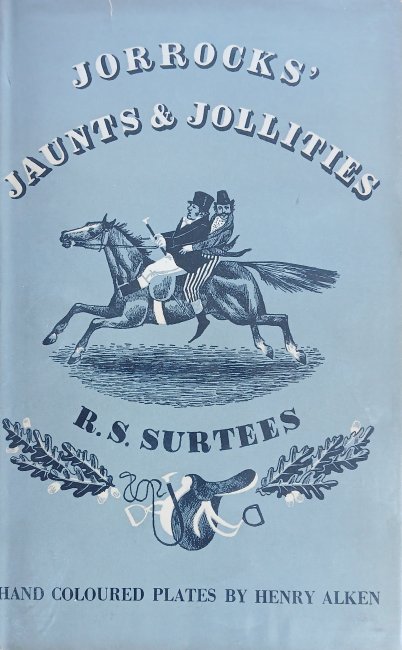

In 1949 The Folio Society decided to have a go at resurrecting the works of Robert Smith Surtees who had sadly dropped out of fashion since his heyday in the Victorian period with an edition of his first book, indeed his books used to be so well known that Virginia Woolf referred to this very title in the 1925 novel ‘Mrs Dalloway’ as her eponymous character was searching for a book suitable to take to a nursing home.

This late age of the world’s experience had bred in them all, all men and women, a well of tears. Tears and sorrows; courage and endurance; a perfectly upright and stoical bearing. Think, for example, of the woman she admired most, Lady Bexborough, opening the bazaar.

There were Jorrocks’ Jaunts and Jollities; there were Soapy Sponge and Mrs. Asquith’s Memoirs and Big Game Shooting in Nigeria, all spread open. Ever so many books there were; but none that seemed exactly right to take to Evelyn Whitbread in her nursing home.

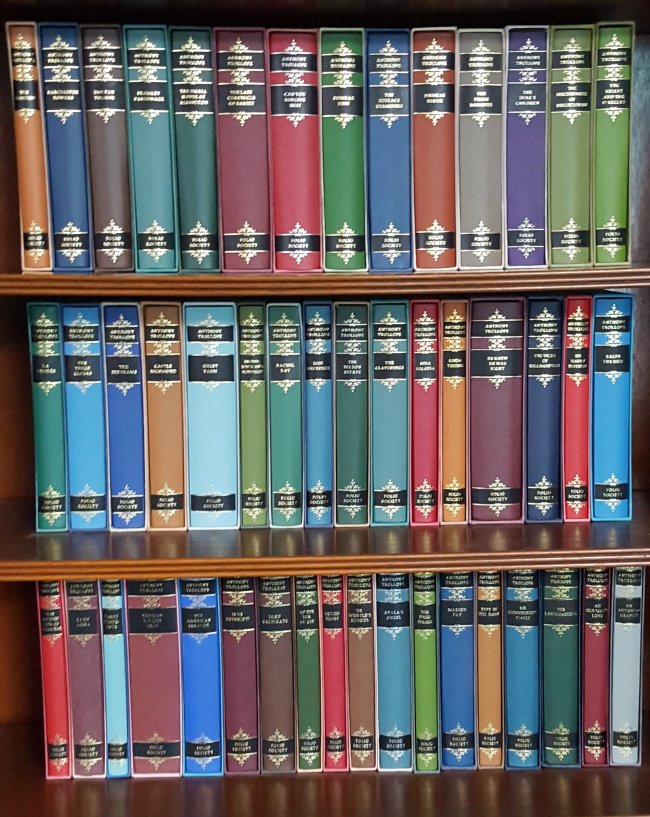

Frankly if I was in a nursing home then Surtees may well be just the right author for my convalescence as the books are well written, with excellent observations on country life and Jorrocks is one of the great comic characters of the early Victorian age. This book was printed in only the third year of The Folio Society’s existence and was intended as a one off from this author in companion with a similarly designed edition of The Compleat Angler by Izaac Walton. However it was so popular that they subsequently published the remaining seven books by Surtees at the rate of one a year, making Surtees the first author to have their complete works published by the society.

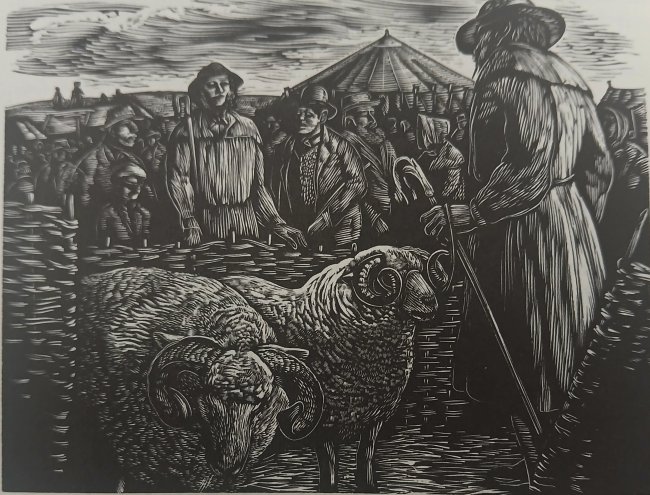

John Jorrocks is described as a grocer in the book but as he operates out of his own warehouse rather than a shop he is probably a fairly wealthy wholesaler based in London. He is a keen fox hunter, riding with the Surrey hounds based at the small country town of Croydon about ten miles from central London. Anyone who knows Croydon nowadays, it has a population of around two hundred thousand and has been largely subsumed by Greater London, will find the rural descriptions of the place in the 1830’s difficult to imagine but this really was the case back then. Jorrocks’ regular companion is Mr Stubbs who is normally simply referred to as The Yorkshireman and one of the funniest passages in this book describes a ride from the middle of London by both of these gentlemen to join the hunt on a particularly foggy day in the city with the chaos they cause or get involved in. As Surtees is not well known nowadays I’m going to include a couple of examples of his style. The Yorkshireman never seems to have any money but is quite happy to live off Jorrocks as in this plan for a weekend trip.

“Now to business—Mrs. J—— is away at Tooting, as you perhaps knows, and I’m all alone in Great Coram Street, with the key of the cellar, larder, and all that sort of thing, and I’ve a werry great mind to be off on a jaunt—what say you?” “Not the slightest objection,” replied the Yorkshireman, “on the old principle of you finding cash, and me finding company.” “Why, now I’ll tell you, werry honestly, that I should greatly prefer your paying your own shot; but, however, if you’ve a mind to do as I do, I’ll let you stand in the half of a five-pound note and whatever silver I have in my pocket,” pulling out a great handful as he spoke, and counting up thirty-two and sixpence. “Very good,” replied the Yorkshireman when he had finished, “I’m your man;—and not to be behindhand in point of liberality, I’ve got threepence that I received in change at the cigar divan just now, which I will add to the common stock, so that we shall have six pounds twelve and ninepence between us.” “Between us!” exclaimed Mr. Jorrocks, “now that’s so like a Yorkshireman. I declare you Northerns seem to think all the world are asleep except yourselves;

Jorrocks also loves his food and drink and there are long descriptions of meals and consuming numerous bottles of wine and port in one sitting. I particularly enjoyed the contrast between the eating manners of the English and French when Jorrocks takes The Yorkshireman with him on a trip to Paris and the slow appearance of course after course in France confuses him rather than the everything on the table to start with which was then the preference in England and he assumes he is going to starve due to the lack of visible food. Early on in the book he invites The Yorkshireman round for breakfast before heading out to the hunt.

About a yard and a half from the fire was placed the breakfast table; in the centre stood a magnificent uncut ham, with a great quartern loaf on one side and a huge Bologna sausage on the other; besides these there were nine eggs, two pyramids of muffins, a great deal of toast, a dozen ship-biscuits, and half a pork-pie, while a dozen kidneys were spluttering on a spit before the fire, and Betsy held a gridiron covered with mutton-chops on the top; altogether there was as much as would have served ten people. “Now, sit down,” said Jorrocks, “and let us be doing, for I am as hungry as a hunter. Hope you are peckish too; what shall I give you? tea or coffee?—but take both—coffee first and tea after a bit. If I can’t give you them good, don’t know who can. You must pay your devours, as we say in France, to the ‘am, for it is an especial fine one, and do take a few eggs with it; there, I’ve not given you above a pound of ‘am, but you can come again, you know—waste not want not. Now take some muffins, do, pray. Batsey, bring some more cream, and set the kidneys on the table, the Yorkshireman is getting nothing to eat. Have a chop with your kidney, werry luxterous—I could eat an elephant stuffed with grenadiers, and wash them down with a ocean of tea; but pray lay in to the breakfast, or I shall think you don’t like it. There, now take some tea and toast or one of those biscuits, or whatever you like; would a little more ‘am be agreeable? Batsey, run into the larder and see if your Missis left any of that cold chine of pork last night—and hear, bring the cold goose, and any cold flesh you can lay hands on, there are really no wittles on the table.

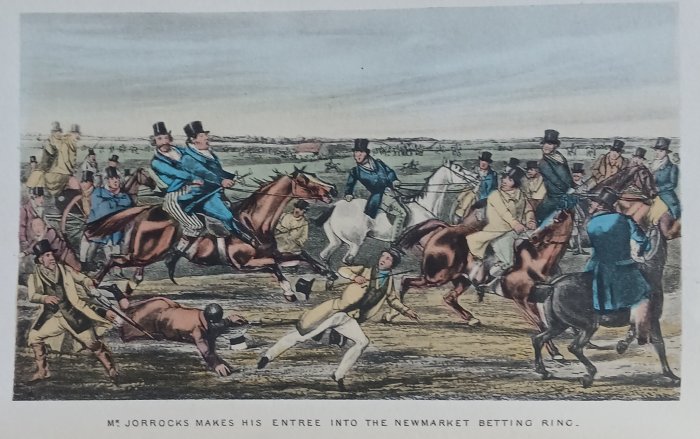

A note should be made regarding the fifteen colour plates included in the book as they were done by a technique that had largely disappeared by 1949. The plates, which are those by Henry Alken originally included in the book back in 1838, were in fact printed in monochrome and individually hand coloured by Maud Johnson who went on the do the same for the further seven volumes Folio printed of Surtees’ works. The Folio Society doesn’t include printing numbers for their books in the various bibliographies they have published but it can be imagined what a huge amount of work this involved for one person, but the effort was worth it as these illustrations really stand out. The pages for the prints are noticeably thicker and stiffer than the pages of text presumably to allow for Johnson’s use of watercolours to do the colouring without distorting the paper. Other than special very limited editions these eight volumes are the last books with hand coloured plates printed in England that I am aware of although I’d love to know of any others. The Folio Society continued to use the original plates throughout the series of reprints which was finally complete in 1956 with this being the only one illustrated by Alken, most of the others are done by John Leech.