Originally published by Hutchinson in 1962 and reprinted as a paperback by Penguin in 1965 this is now really more of a historical document a a lot of ‘The London Nobody Knows’ could really be retitled ‘The London Nobody Knew’ if reprinted today as quite a lot of what is featured no longer exists or has changed so dramatically as to be unrecognisable. For example the chapter dedicated to Islington refers to bomb damaged buildings and shops still in need on preservation, definitely not the case nowadays where in 2024 the average price for a terraced house there was £1,600,000 and a semi detached home getting on for 2 million pounds. I love the fact that Islington could be regarded as part of London nobody knows.

The book marks the beginning of the over thirty years Fletcher wrote and illustrated a diary column for the Daily Telegraph newspaper. As a young man in 1945 at the end of WWII he came to London to study at the famous Slade School of Fine Art and later at the Bartlett School of Architecture and brought his knowledge and art ability to the fore in his columns and his books. He died in 2004 at the age of eighty one back in his birthplace of Bolton and wrote, along with his newspaper work, at least thirty books of which this was the second. Of the books I have found listed two thirds are about London and almost all the rest are about how to paint and draw so he was dedicated to his subject and it shows in this delightful volume. There are two very different styles to the forty two drawings included, three of which are of the cast iron gents toilets in Star Yard, Holborn which I’m pleased to say is still there as a remnant of Victorian plumbing although no longer functional. I have chosen two illustrations to show both the finished drawings and what must really be regarded as sketches, the first being St Anne’s church in Limehouse, one of three churches he describes in that locality, another being Christ Church, in Spitalfields which he comments is in danger of demolition but is definitely still standing today and in regular use.

The title of the book has had a few dissenters over the years as ‘The London Nobody Knows’ is somewhat condescending to the many hundreds of thousands of people that live in the parts of London featured and know all too well in some cases. Whilst researching this article I found one comment that it should have been called ‘The London Nobody Who Reads The Telegraph Knows’ as it mainly covers parts of London that the more wealthy readers of that newspaper would have frequented although now of course a lot of it has been gentrified over the years.

Sadly the building I chose to demonstrate the more sketch like drawings, the Grand Palais Yiddish Theatre on Commercial Road, Whitechapel, was a bingo hall by 1962 when the book was written and was demolished in 1970. Whilst admiring the artistry of the more finished drawings I love the sketches as he captures the life of the people around the featured properties and you feel more drawn in. The suggested perambulations to find the buildings, or even lampposts and signs covered in the text are also a joy to read.

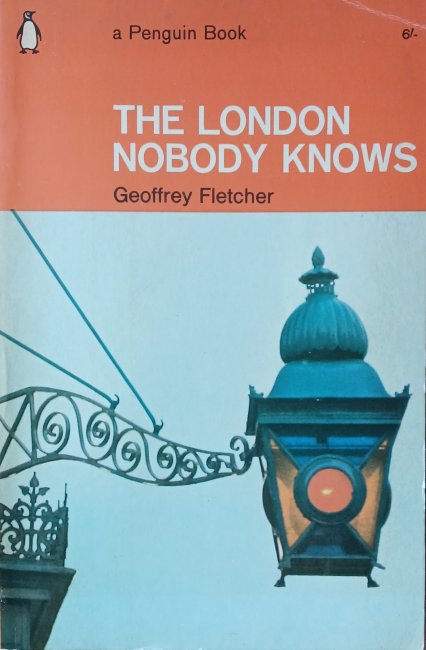

Annoyingly much as I would love to know where that multicoloured lamp is on the front cover, neither the photographer nor their subject is credited in the book, something at the time that Penguin Books were all to prone to do. Two years after my copy was published there was a documentary film of the same name based on the book where actor James Mason wanders round some of the places featured and parts of this are available on youtube including this bit about The Roundhouse, now a major music venue,and illustrated in the Camden Town chapter of the book.