As I’ve covered before, 2025 marks the ninetieth birthday of Penguin Books, and regular readers of this blog have no doubt realised I am a keen collector of this publisher. There are many different ways to collect Penguin books and one popular way is to collect the first five hundred, or first thousand, or if you really have the space then the first three thousand main series titles (those generally recognised as Penguins). This co-incidentally is pretty well all the main series books published by them from when they started in July 1935 up to the introduction of ISBN and the loss of the distinctive numbering system so it is a satisfying, if bulky, target to aim at. There are problems with this though as quite a few of the wartime titles, especially the crime fiction, are now very expensive, so I’ve been thinking about what I would do if I was starting now and one possibility is the Penguin Millions. These are a subset of the Penguin titles and importantly the first ‘million’ came out in 1946 so the scarce wartime crime titles can be avoided. But what is a Penguin Million and how many are there?

The first million has an explanation of the concept on the inside, in this case George Bernard Shaw had reached his ninetieth birthday in July 1946 and to mark the occasion Penguin simultaneously printed a hundred thousand copies of each of ten books. Nine of these were new to Penguin (books numbered 500 along with 560 to 567) and there was one reprint, Pygmalian (numbered 300 and originally printed in September 1941). Nowadays I doubt a million books by Shaw would sell very well but back then he was still a popular author and his works are regularly found in early Penguin lists and these titles were soon being reprinted again..

The idea obviously sold well enough for somebody at Penguin to decide that this was a good idea and the second million soon followed a couple of months later in September 1946 and this time the author featured was H.G. Wells

This time there were three titles reprinted as part of the set, A Short History of the World (Pelican A5 original May 1937), The Invisible Man (151 original August 1938), Kipps (335 original November 1941), with the remaining seven books being numbered 570 to 576 and coming out together in September 1946. Maybe these didn’t do as well as Penguin though they would as there was then a gap of a couple of years before they had another go and this time it was the sure fire winner Agatha Christie,

Published in August 1948, this time all ten books were new to Penguin so they had the consecutive numbers 682 to 691. Considering that a hundred thousand copies of each were printed Murder on the Orient Express as part of the Christie Million is surprising awkward to find and is probably the only book featured in this list that would be a real challenge to locate. Although tracking down some of the correct reprints for other titles can also be tricky, as they are rarely advertised as being part of their respective ‘millions’ when searching online but you can always tell if it is correct edition as it will have the page explaining about its part of the set.

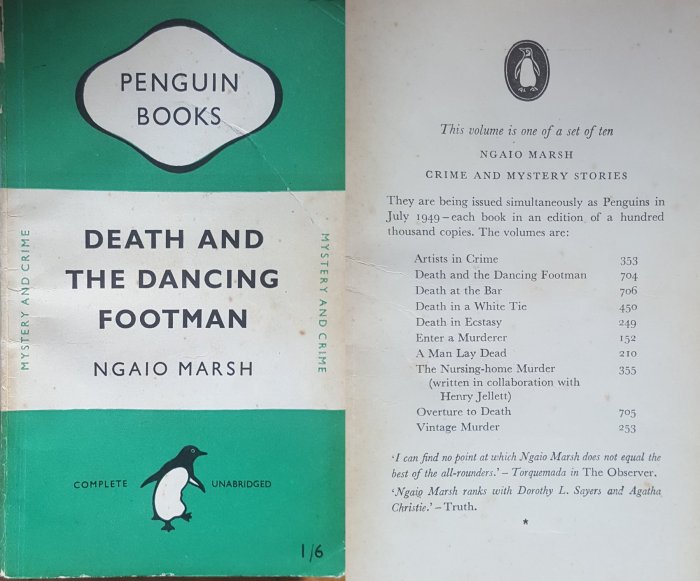

Another eleven months passed and it was time for another crime writer to be featured, this time New Zealander Ngaio Marsh.

This time Penguin have made it easy for me and given the respective numbers in the Penguin catalogue in the listing. As you can see only three titles were new to Penguin (numbers 704 to 706 published July 1949) with the others going back as far as Enter a Murderer (152 – August 1938). This is where the financial advantage of collecting the ‘millions’ editions comes into its own as Death in a White Tie would sell for well over £500 and possibly getting on for £1000 as the March 1945 Penguin first edition whilst the reprint for the ‘million’ is only a few pounds. This reprint is also a Penguin oddity as the floor plan of the house where the murder took place is missing from this edition and was incorrectly included in 704 Death and the Dancing Footman. Both books are therefore somewhat confusing for readers, one for the lack of the diagram which makes placing the action more tricky, and the other for an included plan of a house that bears no relation to the plot.

The next million was in March 1950 and we leave the world of crime in favour of a somewhat more challenging read, D.H. Lawrence to mark the twentieth anniversary of his death.

As can be seen five of the books chosen were ‘double volumes’ marked with an asterisk in the list above, i.e. books of significant length and were therefore more expensive than the standard paperback at the time, which retailed at one shilling and sixpence (7½ pence), these longer books were two shillings and sixpence (12½ pence). Kangaroo for example is 594 pages. All of the books were first printings by Penguin nine of which are 751 to 759. The original plan was for 760 The White Peacock to be included in the ten books but production issues meant that this wasn’t ready for publication until August 1950 so the collection of poems (D11) was issued instead, which, along with the separate volumes of letters and essays, I think gives a wider overview of D.H. Lawrence’s work as part of this collection.

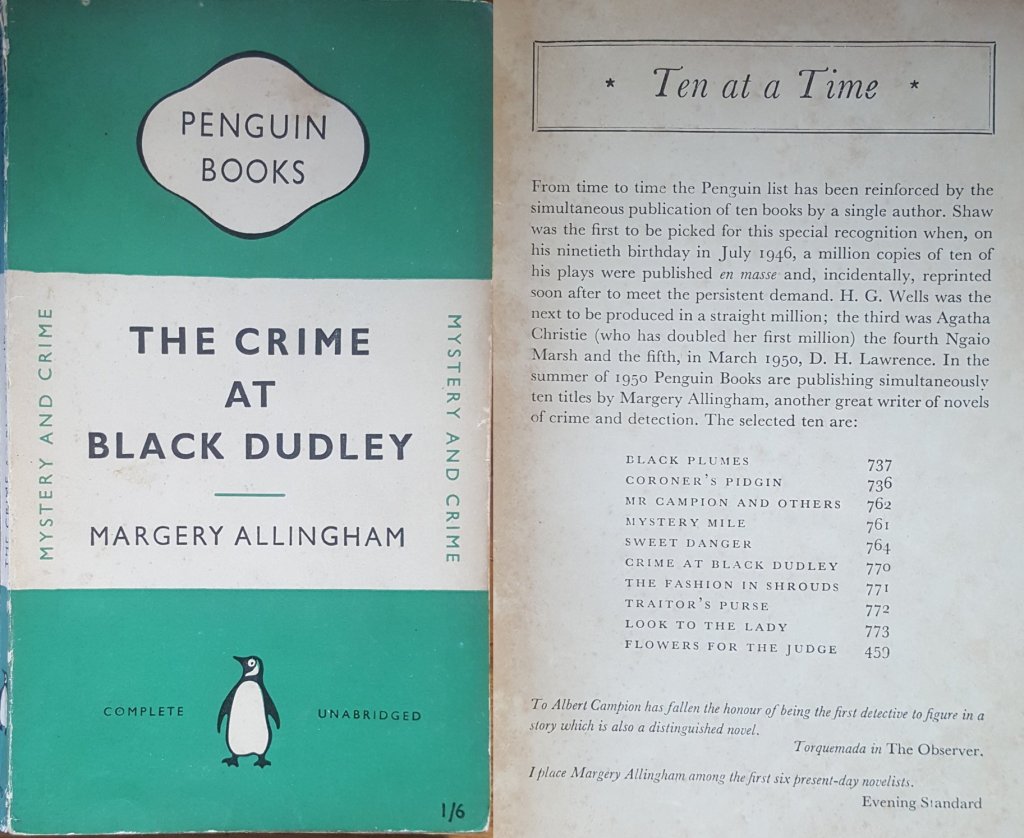

After the erudite literature of Lawrence it was back to crime for the next Penguin million. This time Margery Allingham in June 1950.

The only reprint is another wartime crime rarity 459 Flowers for the Judge (originally June 1944) all the others, despite the apparently random numbers, all first appeared as a UK Penguin in June 1950. The one oddity is 737 Black Plumes which had first been printed by Penguin USA Inc as number 534 in December 1943 and is another difficult to find wartime first Penguin printing, especially on this side of the Atlantic.

Next comes Evelyn Waugh whose ‘million’ came out in May 1951.

This time there are five titles new to Penguin (821 to 825) with five reprints Decline and Fall (January 1937), Vile Bodies (April 1938), Black Mischief (November 1938), Put out More Flags (October 1943) and Scoop (March 1944). There’s a nice potted bibliography along with the list of books in the listing. I’ve always quite liked Evelyn Waugh although he does seem to be a lot less well known nowadays. I also like the fact that his first wife, although only for one year as she had another relationship with John Heygate at the time, was also called Evelyn, just imagine the confusion when guests called.

We then start a run of three crime novelists before the ‘millions’ peter out and next comes Carter Dickson in June 1951.

Again we have ten new titles, consecutively numbered 811 to 820 and all by Carter Dickson, who also wrote under his real name John Dickson Carr as well as Carr Dickson and as a real wildcard once as Roger Fairbairn. Fortunately his ingenuity with plots is far better than his imagination with pseudonyms and the missing photograph on the back cover with it’s accompanying blurb regard anonymity fooled nobody. However regarding the use of the back cover here, I have had to do this as, due to a compilation error, all ten of the books actually have the Evelyn Waugh ‘millions’ description inside them instead of one for Carter Dickson. Almost all the books he wrote under the name Carter Dickson feature the elderly amateur detective and barrister Sir Henry Merrivale and that is certainly the case with the ten books in this collection. I personally prefer the Dr Gideon Fell stories he wrote under his actual name although that possibly because I came across him first. Each of these detectives have around a couple of dozen books dedicated to them and the Merrivale books certainly have much to recommend them.

The next million goes to Belgian George Simenon and his legendary detective Maigret and these were published in January 1952.

Simenon is invariably though of as French like his most famous creation Jules Maigret, as Penguin do so in the introduction above, and he did live for a lot of his life in France along with a decade or so in America after WWII. There are seventy five Maigret novels and numerous short stories but even the novels are quite short so Penguin tended to publish two per book. The collection came out as two blocks of numbers 826 to 830 and 855 to 858 which count for the nine new to UK Penguin Simenon titles in the ‘million’ there was also a reprint 739 A Battle of Nerves & At the ‘Gai-Moulin’ (originally January 1950). Yet again we have a book that was first printed in America as a Penguin Inc publication, Maigret Travels South which first appeared under the Penguin logo in New York as 564 (September 1945). The works of Simenon have a very chequered history with Penguin with many volumes being announced but never actually being published.

Where do you go after the classic Maigret novels well there can only be one choice and the only author to have multiple ‘millions’ it’s Agatha Christie again, this time in May 1953.

This time Agatha Christie chose the ten titles herself and oddly one of them had already appeared in the first Christie million so we have nine books (924 to 932) printed by arrangement with Collins which are first appearing in Penguin along with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd which had first been printed by Penguin as 684 in the first Christie million in August 1948. Technically all ten of these books are a first edition as each includes a new introduction written by Agatha Christie for this printing.

And that was it for the printing of ‘millions’ but there was one final addendum and that was for Arnold Bennett

This time there were only six books issued at the same time and no suggestion that a hundred thousand copies of each were being printed. Two were reprints Anna of the Five Towns (33, March 1936) and The Grand Babylon Hotel (176, November 1938) along with four that were new to Penguin (996 to 999) and as can be seen there were various issues with copyrights in Canada and the USA.

So where does that selection of eleven sets of publications within the first thousand bring us, well there are 106 (105 if you don’t want Roger Ackroyd twice) books to search for, eleven largely readable authors, both Bennett and Shaw I have to be in the mood for, and a pretty decent fiction library from the end of the 19th century through the first half of the 20th. Plenty of easy reading crime and other novels with some more taxing works but none that should put off a dedicated reader. It is also a manageable task to accumulate all of these without the bank account straining issues that can face a collector of a complete numeric run. I have been collecting Penguin for over thirty years, although I only really started taking the main series seriously in the last dozen or so as I mainly concentrated on the more obscure aspects of their output. But I’m still missing fourteen books out of the first six hundred even after twelve years and I’m only very very slowly filling in the gaps.

There are many more blocks of books by one author after number 1000, but as I don’t collect them I cannot pull them off the shelves to check to see if any of these are designated as ‘millions’. Examples include six books by Aldous Huxley numbered 1047 to 1052 published in April 1955, eight books by C.S. Forester numbered 1112 to 1119 published in January 1956 (1111 is also by Forester but came out two months earlier), and nine books by John Buchan numbered 1130 to 1138 which were published in May 1956. Maybe collecting the ‘millions’ is the way ahead.