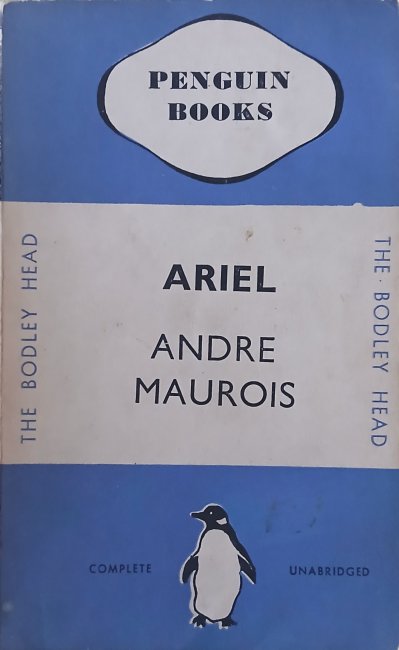

30th July 1935 was a very important date in the history of publishing, as that is when the first ten Penguin books made their appearance. Ninety years later these books in their first editions are somewhat fragile and definitely difficult to find, especially the crime titles. I do have all ten and seven of them still have their elusive dust wrappers as can be seen below, the wrappers have the 6d (six pence) price on the front cover. For August I’m going to be reading the first four, one a week, and the plan is to read five of the remaining six during the rest of the year, one has already been a subject of a blog so this will be linked to when its turn comes, I will probably re-read this one as well just to say I’ve read the set in a run. As the books are so delicate, and valuable, this is not something I have done before but it only seems appropriate as a means to celebrate Penguin’s 90th birthday. The books are colour coded with blue indicating biography, orange fiction and green crime, other colours would be introduced as time goes on. This was a concept started by Albatross Press in Germany, see my blog on those books for more details and the similarities between them and Penguin.

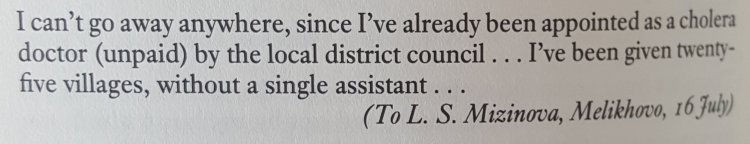

Before talking about ‘Ariel’ the book there is one other thing that needs to be mentioned regarding these first ten books and that is an error on the back of the very first versions of all of them. Book two, ‘A Farewell to Arms’, is missing its first word in the list of titles on the rear. This was noticed quite quickly but not in time to prevent the first batch of titles going out with this incorrect list. Subsequent batches of books from the first editions of all ten books were corrected and the full title appears, however another error happened with ‘Ariel’and this is clear on the front cover at the top of this log entry. The authors first name is André not Andre and this led to a third cover being produced for the remainder of the first edition run of this title, not a great start to a new publishing enterprise. The first edition is therefore available in three variants:

- Farewell to Arms on the rear and Andre on the front

- A Farewell to Arms on the rear and Andre on the front

- A Farewell to Arms on the rear and André on the front

All three versions are shown below, the first book being the rear of the one used at the top of the page with the missing accent, the second book is also missing the accent on the front cover.

Another thing to add, as it is clearer at the base of the rear covers above, is that Penguin Books when it began was simply a paperback imprint of the publisher John Lane The Bodley Head which explains why all the books say THE BODLEY HEAD on their front covers. This would be the case for over a year with Penguin Books finally becoming a separate entity and references to The Bodley Head no longer appearing from the batch of books numbered 81 to 90 published in March 1937.

When reading ‘Ariel’ it becomes clear that its subtitle ‘A Shelley Romance’ is particularly appropriate, as whilst it reads as a biography of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley it is at least partially a novel with a lot of clearly invented dialogue with no documentary evidence behind it, rather than what we would regard as a properly researched scholarly work today. That said the general thrust of the book and the sequence of events is accurate and it is impossible to examine the extent of Maurois’ actual research due to the lack of notes, citations or even an index in the book. Maurois is clearly more interested in getting a feel for his subject and portraying him in a way that gives an impression of what it would have been like to know him rather than providing a definitive biography, but it is very readable and still in print, both in this translation by Ella D’Arcy and other more modern versions.

We follow Shelley from his time being badly bullied at Eton, going on to Oxford where he lasted just a few months before being expelled from the university along with his friend and fellow student Thomas Jefferson Hogg over the authorship of a pamphlet entitled ‘The Necessity of Atheism’ which he had mailed to the bishops in the area and the heads of all the Colleges. Whilst at Oxford he had met Harriet Westbrook, a sixteen year old school friend of his sisters whom shortly after his nineteenth birthday he eloped to Edinburgh with. This led to their considerable financial difficulties as both sets of parents were outraged and stopped their allowances. Shelley had two children with Harriet, the second born after he had run away to France with the sixteen year old daughter of William Godwin and her sister whilst believing Harriet had begun an affair. Mary of course became famous as the author of Frankenstein which was published and went on to write several other novels after Shelley’s death but Maurois completely ignores this side of her portraying her as a dedicated wife, they married just days after after Harriet’s suicide, but also covering domestic arguments mainly between her and whichever other people (usually other women) were living with them at the time. The lack of acknowledgement of Mary’s literary talents is possibly the greatest failure of this biography. During the coverage of Shelley’s extended time in Italy, until his death there at just twenty nine, the quality of the biography improves markedly with letters included and far more evidence provided for what Maurois states happened.

Sadly Shelley never enjoyed the fruits of his poetic labours, as at his death he was still barely read and his life too coloured by his socialist and atheist reputation to make him acceptable reading for anyone likely to see his works in print, which is ironic bearing in mind his status as one of the great Romantic Poets nowadays. By all means read this book by Maurois as a general overview of the life of Shelley, but if you are really interested in the poet I have to recommend ‘Shelley: The Pursuit’ by Richard Holmes, first published in 1974 but still the definitive work.