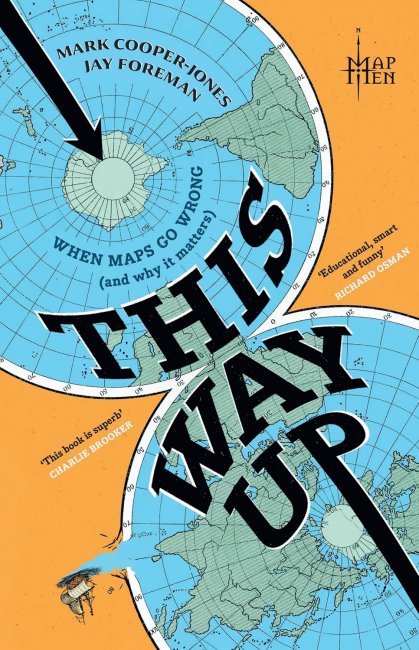

This largely highly entertaining book looks at maps and what happens when they are wrong for any of a multitude of reasons. It is written by Youtube creators Mark Cooper-Jones and Jay Foreman aka MapMen. If that first sentence appears to be hedged somewhat, that is because it is, and I will come back to why towards the end of this blog but first let’s look at the good bits which is the vast majority. I’ve read books on the same theme before, notably Edward Brooke-Hitching’s The Phantom Atlas, which is listed as a source in the bibliography of this book and was clearly the basis of the section on The Mountains of Kong (Chapter 4 The Map That Made Up Mountains) and which I covered in my review of The Phantom Atlas.

There are many map stories that I hadn’t come across before including the story of the remarkable navigation feats of the people of the Marshall Islands who can travel between the vastly spread out islands and atolls simply by noting the movement and pressure of the waves, well we think that’s how they do it, it’s probably a lot more complicated than that. Another fascinating story is of The Situationists, a small French anti-capitalist organisation who rejected traditional maps replacing them with diagrams indicating relationships between places. That Cooper-Jones and Foreman decided to illustrate this by trying to meet for lunch in London using maps of Paris is a suitably surreal experiment that failed but admirably made the point. The story of the television station map of the UK was informative and odd at the same time. I remember the various regions but had never really thought about how strange they were before now. Another tale I sort of knew was the IKEA world map that left off New Zealand but I wasn’t aware of just how common this is, to the point that maps with this geographical mistake have a dedicated reddit group. It should be noted here that chapter 3, where the authors use maps of Paris in London, starts with a QR code which links to a Spotify playlist to be listened to whilst reading, an idea I’ve never seen before in a book.

But let us look at a couple of places where the writers rather than the maps go wrong, the first one I spotted is a straight factual error. Chapter twelve, which ironically is about places being mis-located on maps, states that CNN produced a map that put the Libyan capital Tripoli in Syria for a piece about Colonel Gaddafi. and then later that chapter explains the mistake as:

Take for instance CNN’s map that misplaced the Libyan capital Tripoli in Syria. There is a Tripoli in Syria but it definitely wasn’t where Gaddafi was hiding at the time, and nor were CNN intending to suggest so.

Despite this assertion, in fact there isn’t a Tripoli in Syria, there is however the coastal city of Tripoli in the adjacent country of Lebanon which is presumably where CNN placed their map reference, not Syria at all. I must admit I picked up on this because I’ve been to both Tripoli’s, both in Libya and in Lebanon and whilst I liked both I wouldn’t recommend going to either currently for various geopolitical reasons.

For me though the biggest fault in the book is the longest chapter ‘The Deadliest Shortcut’ and it’s not for a factual error but rather for the badly misjudged tone of the chapter. Now I know this is supposed to be a humorous book, and yes it is very funny, whilst making excellent and quite serious points regarding maps and their use. But this chapter, written as a podcast, descends into almost slapstick jokes with people talking over one another, whilst describing the horrific ordeal of the 19th Century American settlers known as The Donner Party. For those people unaware of this story The Donner Party refers to a group of 87 settlers, including children, heading for California in 1846 who start falling behind the main groups and decide to take a shortcut shown on a map they had, but which crucially had been put there by somebody who had never actually made the journey. The group of families became trapped in the snow by what is now known as Donner Lake in the Sierra Nevada mountains and by the time they were rescued the following year only 48 out of 87 made it to California and the trapped group had largely survived by eating the dead, two of which were guides who were killed to supply food. Clearly a subject that should be handled with care and compassion, not with jokes and especially not in the cack handed manner exhibited here.

All in all I greatly enjoyed the book and with the exception of the aforementioned chapter ten I heartily recommend it.