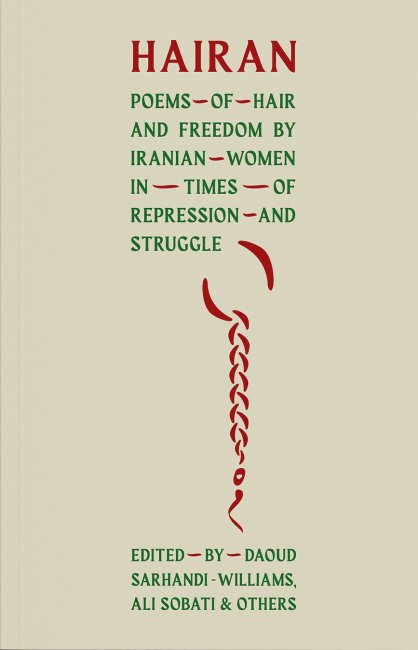

This book was inspired by the killing of Mahsa Amini by the Morality Police in Iran apparently for not having her hair properly covered by her hijab. This murder in 2022 added further outrage to a movement that was already existing in the country known as Woman Life Freedom which opposes the oppression of women not only in Iran but neighbouring countries such as Afghanistan. I have featured works both from and about Iran several times in the past and when I spotted this book in a shop last month I was inevitably drawn to it, I especially like the title combining the provocative word hair, which for women must at all times be hidden in public, with the name of the country.

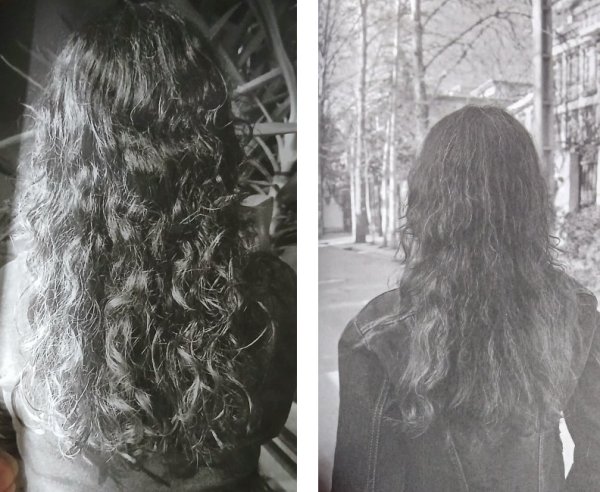

The book is much more than simply a collection of poems, most of which were especially written for this collection, as there is also a very informative introduction which covers the history of female poets in Iran going back to the days of the Persian empire. This introduction also includes brief remarks about several of the poems in the collection, setting them in context. There are also thirteen black and white photographs of Iranian women from the back showing their hair, with clearly no identifying information in order to protect them from the regime and several political posters supporting the Woman Life Freedom movement. One thing the editors were surprised by was the refusal by any of the poets included to use a pseudonym or be credited anonymously especially bearing in mind the topics covered.

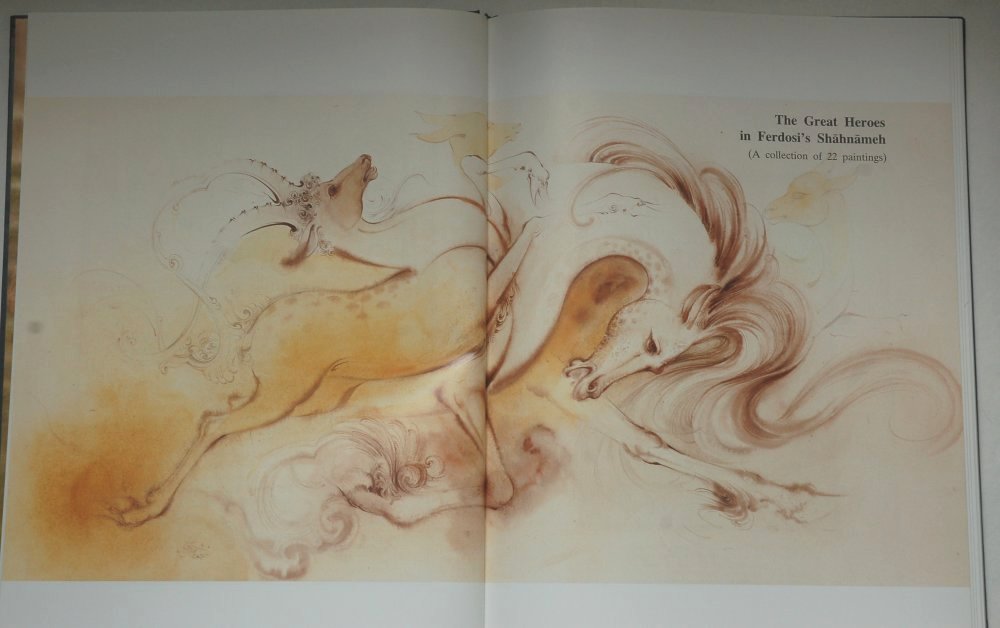

The poems are powerful in their imagery and in sorrow and outrage at the treatment of women and sometimes men who support them. If a poem needs more explanation for those of us that don’t live in Iran and therefore haven’t been exposed to names, places or events referred to there are useful notes after the poem. Several poems refer to Ferdosi’s epic Shahnameh, which I briefly covered in 2018 as the story is a classic in Persian culture and familiar to most Iranians. Whilst reading I was noting any poems that I thought I could pick out in this review as I particularly enjoyed them and ended up with twelve of the seventy six which is clearly too many to list but emphasises how strong this collection is. However I particularly want to mention “This Place” written by Atefeh Chararmahalian during her 71 days incarcerated in the infamous Evin prison in Tehran along with “You’d Said” by Fanous Bahadorvand and “freedominance” by Leila Sadeghi which are both explicit tributes to Mahsa Amini as is the poem I have chosen to represent all the others:

The three young women included in the dedication are Mahsa Amini (aged 22 when killed in police custody), Nika Shakarami (aged just 16 when abducted by the security forces and killed sometime during the next ten days, who know what happened to her during that time) and Hananeh Kia (aged 23 when shot by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard near a protest whilst walking back from the dentist, she was due to get married just two weeks later). Nika’s body was never returned to her family and she was instead secretly buried by the security forces forty kilometres away presumably to avoid her funeral becoming a flash point for more protests.

The book is published by Scotland Street Press, who I must admit I hadn’t heard of before purchasing this collection, but looking at their online catalogue they seem to have quite a few titles that are very interesting, so I don’t think this will be the last book of theirs to make it to my library. I’ll finish with a couple of the images of Iranian women’s hair from the book including one very bravely out in the street without a hijab.