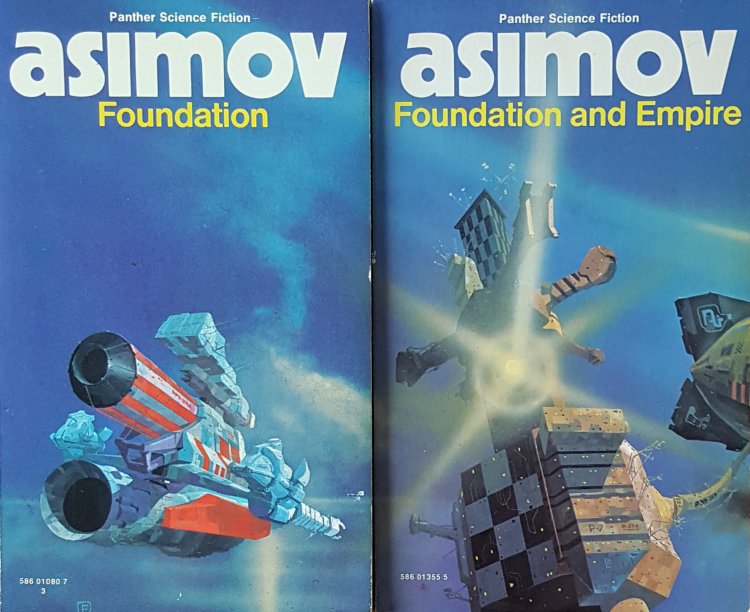

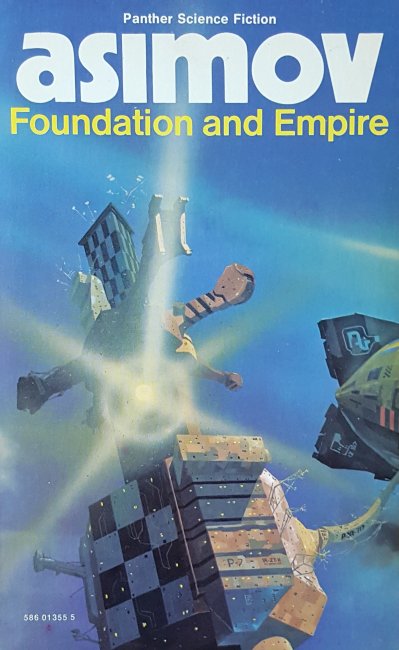

Continuing my reading of the Foundation trilogy by Isaac Asimov we have reached the second volume, my review of the first book can be found here.

This book consists of a longish short story (just over 50 pages) and a novella (113 pages) and continues the story of the Foundation on Terminus, both were first published in Astounding Science Fiction before being combined in this book in 1952.

The General (originally published in April 1945 as Dead Hand) – Set roughly 40 years after the end of the first book so 205 years after the creation of the Foundation on Terminus this short story reveals that the Galactic Empire is still considerably stronger than the Foundation believes it to be and is even now capable of launching an all out attack. Two men hope to stop them and they are prisoners of the Empire, Lathan Devers, a reckless trader and Ducern Barr, son of Onum Barr who had met Master Trader Hober Mallow on his investigations of the dangers of the Korell republic in the story The Merchant Princes.

The Mule (originally published in two parts November and December 1945) – It is now 300 years since the Foundation on Terminus was established and 80 years after the death of Lathan Devers and the trader planets are more or less independent of The Foundation which has come under a despotic ruling family. The Mule is an unknown, a mutant who has apparently effortlessly built himself a fleet and an empire and now threatens The Foundation. This story highlights why Asimov never became a mystery writer (although he did have a go at the genre), there is supposed to be a major twist at the end but I had guessed it within a couple of pages of the character being introduced right at the beginning of the novella. For all that though it is an entertaining story with a strong female lead character, which was somewhat unusual in 1940’s science fiction.

Coming to the end of the second book in the trilogy I realised something else about Asimov’s science fiction and that is the almost complete lack of aliens in any of his writing. The Foundation trilogy covers the entire galaxy but nowhere is there an alien species; it is covered instead in humanity that has spread out from a semi-mythical home planet millennia ago. I have read dozens of his books and apart from one short story, written for Playboy, and the much later novel The Gods Themselves (written in 1972) I cannot remember there ever being an alien species referenced and this is odd. Asimov was a professor of biochemistry at Boston University so was certainly aware that where life can exist it will, at least on Earth, why did he not then extend this to encompass life on other planets? It is suggested in the Wikipedia article about him that when he was starting out an early story was rejected for having aliens more powerful than humans so he decided to not write about them at all, but I don’t buy that explanation as other authors had powerful aliens so maybe we’ll never know the true reason for his humanocentric universe.

As teased in the first review the covers join together to make a whole image, with the first two books it is less obvious but if you follow the smoke and light trails you can see that we are looking at two thirds of one painting. It must have been tricky to select this as each cover has to work on its own whilst also being part of the whole thing.