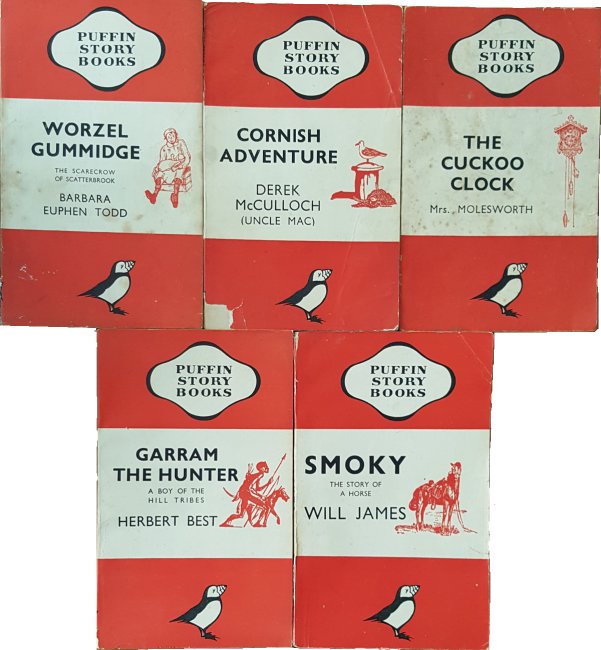

These three charming books were printed by Puffin Books in the 1940’s. They don’t seem to have been reprinted, not just by Puffin but by anyone, which bearing in mind that they are for very young readers, or more likely parents reading to young children, and their inherently fragile nature consisting of just eight sheets of paper, including the covers, folded and stapled in their centre makes finding them in good condition extremely difficult. Due to their rarity I have decided to include several double page spreads so that you can appreciate what a delight these little books (182mm x 110mm or 7.16 x 4.33 inches but so thin they are almost pamphlets) are. As implied the three books feature an anthropomorphic railway engine similar to the slightly later, and much more famous Railway Series by Wilbert Awdry and later his son Christopher which feature, amongst others, Thomas the Tank Engine, although that particular character isn’t in the first book which first appeared in May 1945.

The Holiday Train

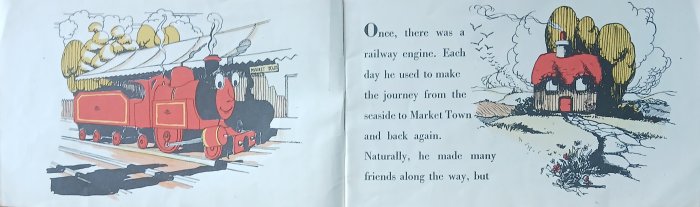

Published in November 1944 as Baby Puffin number five, this introduces The Holiday Train as a character along with the love of his life The Little House which he passed every day whilst travelling up and down the line. Like the Puffin Picture Books, which were well established by then, the books were produced from plates normally cut direct by the artist, But Heaton was not a lithographer and didn’t know the technique so his drawings were converted in house by staff at the printers W.S. Cowell Ltd of Ipswich.

The story actually starts with the older engines, including The Holiday Train, being retired and going off to rest which he was happy about although he was really going to miss The Little House. But the seaside town where he had worked grew in popularity and population so the new engines couldn’t cope and it was decided to bring back the old locomotives.

As you can see above his return didn’t get off to a great start but soon all was well and The Holiday Train could renew his friendship with The Little House until…

The dreadful thing is a violent storm where a lightening strike hits The Little House and destroys it which sends The Holiday Train into depression at the loss of his friend. Trying to work out what to do to bring him back to normal the managers of the railway decide to get him to pull a special train, I love the expressions of the people on this next double page spread.

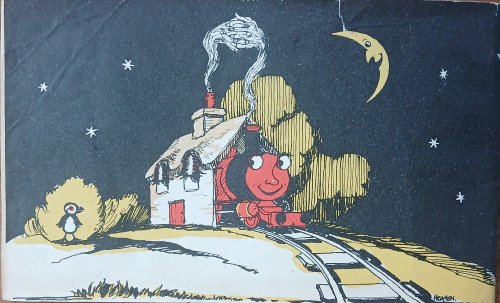

Of course The Holiday Train not only manages but sets a new record for the journey and as a reward it is decided to rebuild The Little House. I particularly like the puffin, the logo of the imprint, hiding behind a bush on the rear cover of the book as the Holiday Train settles down for the night in his new engine shed built from the ruins of The Little House.

The Holiday Train Goes to America

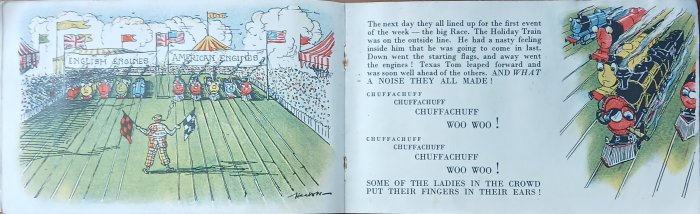

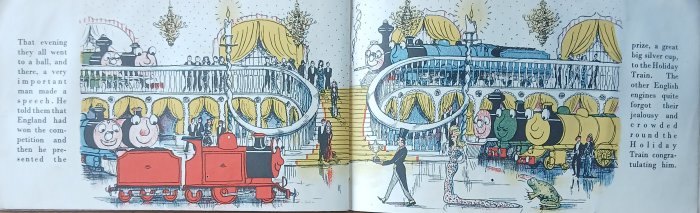

Published in June 1946 as Baby Puffin number six this takes the form of an international competition held in America between five locomotives from England against five from the USA which means of course crossing the Atlantic by ship. Which is a step up from the branch line antics of the first book, even if The Holiday Train is by far the smallest locomotive and is rather looked down on by the others. This book is very different to the other two, not only because of the use of four colour printing which allows for a full colour palate but also due to the much greater amount of text needed to tell a more complex story. This means a significantly smaller font is used, which along with the more literate style makes this definitely a book to be read to a small child rather than one they would read themselves.

Heaton makes full use of his extended colour range, it would have been difficult to do this book without the inclusion of blue. Speaking of which I’m sure the large blue loco called Blue Racer at the back of the left hand image above is a version of Mallard which at had broken the world speed record for a steam train in July 1938 by pulling seven coaches at a peak of 126 miles per hour, a record that still stands today. This can be better appreciated in a later picture where the streamlining of the LNER class A4 is shown, see below.

I love this picture of a seasick train, not a sentence I thought I would ever type, but Heaton manages to capture the abject misery of this condition so well on the face of the engine.

At last they arrive in New York and after being unloaded were welcomed to America and it appears that The Holiday Train runs on a narrower gauge that the mainline locomotives alongside him, which would somewhat explain his size difference. The two locos either side of him above are definitely giving him side-eye.

The three competitions are explained, a race, a beauty competition and a prize for the biggest engine which was almost certainly going to go to an American entrant as they are so much bigger than the locomotives from England. It didn’t look like The Holiday Train stood a chance in any of them. But there was a problem with the huge American engine Texas Tom who suddenly let out a lot of smoke obscuring the view for the other engines, but The Holiday Train is so small that he could see clearly under the dark cloud

and went on to win the race. I haven’t included the picture of the race itself but it does feature one of the errors Heaton made in his artwork as the green English train has vanished along with any tracks for him to run on. Another error is seen above as there is only one blue engine out of the ten and that is the Mallard lookalike but the loco shown above is missing the streamlining clearly depicted a few pages earlier. At the beauty contest there are again only nine tracks and no sign of the English green loco.

At the ball, where The Holiday Train is presented with the cup there are ten locos depicted but yet again Heaton has forgotten that one of the English locos is streamlined. It’s a fun story somewhat let down by the artistic faults, it is possible however that due to the age of the intended readership that this wasn’t noticed at the time by them, however it was spotted by Penguin management.

The Holiday Train Goes to the Moon

The last book in the series, not just of the Holiday Train but of Baby Puffins themselves as an imprint was published in April 1948 as the ninth Baby Puffin. Frankly this is the least interesting of the three titles, having a fairly simplistic story and a return to just red, yellow and black illustrations. It is noticeable that the scale between The Holiday Train and his engine shed formally The Little House has changed somewhat from the first book. In that the loco only just fitted in the picture on the back cover in the original title but now he is inside quite a roomy place with highly impractical curtains and a rug on the floor, see below.

The book tells the story of The Holiday Train being surprised by Carrumpus, a magical character who introduces himself saying “I come to visit trains when they get tired or overworked and cheer them up.” He does this by granting them a wish.

As you can see above The Holiday Train wishes he could fly and soon he has wonderful golden wings so he could fly around rather than running on rails.

Soon he decides to travel to the moon where he finds a railway, but not one like at home as here the carriages pull the locomotive rather than the other way round. But nevertheless The Holiday Train sets off to explore.

Arriving over the town of Lubbelium he sees some strange birds but suddenly Carrumpus notices the time, it’s almost midnight and the wish expires in a few minutes. Quickly The Holiday Train flies back to Earth and his home in The Little House.

It’s a pity that only nine different Baby Puffins were printed but I’m guessing that they were quite difficult for booksellers to display and sell them as they were so thin with no spine and usually were a horizontal format. With regard to the finishing of The Holiday Train books, by April 1948 the first book featuring Thomas the Tank Engine had appeared and he would go on to become enormously popular so did the world really need another anthropomorphic locomotive especially as Thomas and friends were somewhat more realistically drawn although not as delightfully whimsical. The rear cover of this last book has an appeal from Peter Heaton,

Dear Children,

As you know from reading my little books. I like having adventures. If you can tell me of any exciting places I could go to, write to me, care of Penguin Books, West Drayton, Middlesex, England

So clearly Heaton had no idea either that this would be the last anyone would see of The Holiday Train. Although he also wrote and illustrated the eighth Baby Puffin ‘Dobbish the Paper Horse’ Peter Heaton is probably best known to collectors of Penguin books for his Pelican titles dealing with a very different mode of transport, Sailing (first published June 1949) and Cruising (first published April 1952). He served in the Royal Navy during WWII on armed Merchant Navy vessels, corvettes and Motor Torpedo Boats ending up at the Admiralty and after the cancellation of the Baby Puffin series became friends with Penguin Books’ Managing Director, Allen Lane, regularly accompanying him on journeys on his boat. These trips led to the two factual books which made his name and which would be in print for several decades.