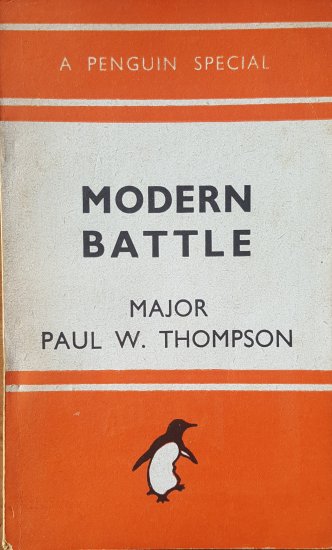

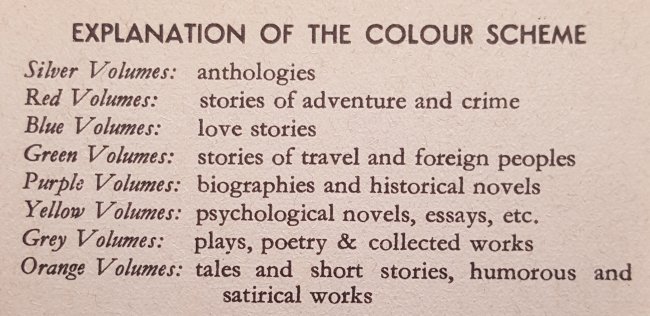

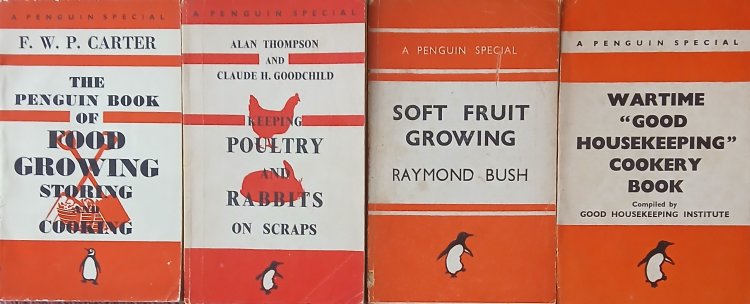

Last week saw the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and this week sees the eightieth anniversary of VE Day, the end of the Second World War in Europe, as this post goes live on the 6th May 2025 two days before VE Day itself. Whilst last week I read Felix Greene’s excellent summary of the first half of the Vietnam War, this week I’m looking at eight books produced as part of the Penguin Specials series which were designed to help the population feed themselves during a time of food shortages and rationing. Penguin Specials were intended to be books dealing with issues of the day and they had rapidly multiplied during WWII with such titles as ‘Aircraft Recognition’, ‘Nazis in Norway’, ‘How Russia Prepared’, ‘Signalling for the Home Guard’ etc. The books were produced far quicker than titles in the other Penguin Series so that they were relevant to the issues of the day, but before the designation of some of them as handbooks there had also been some concerned with making best use of the food supplies however these were in the more usual red covers for Specials. These included ‘S90 The Penguin Book of Food Growing, Storing and Cooking’ (May 1941), ‘S101 Keeping Poultry and Rabbits on Scraps’ (January 1942), ‘S119 Soft Fruit Growing’ (December 1942) and ‘S127 Wartime Good Housekeeping Cookery Book’ (February 1943).

The dates shown below for most of these handbooks may seem quite late in the war for those of us born after the end of shortages and rationing, but it should be noted that general rationing in the UK continued until July 1954 although some items such as bread (1948) did come off rationing before then.

S132 Tree Fruit Growing – Apples – December 1943

Raymond Bush had already written one book for Penguin, as can be seen above, but the two handbooks detailing tree fruit growing took us to his main speciality which he had adopted following a bad accident in 1914 and being advised that an outdoor life would be better for his health than the poster design his company had been doing prior to the First World War. He was a commercial grower from 1915 up until 1935 when he started advisory work on the subject for various scientific committees. The book is a wide ranging guide to growing apple trees with notes where similar methods are appropriate for other fruits such as pears and almost a third of the book is dedicated to pests and how to get rid of them, but it is based on Bush’s determination that the wartime population should not be derived of wholesome fruit. As he says in his introduction “Well my amateur friends, once again you must sit back and watch the Ministry of Food collect most of the fruit to make jam go several times as far as it has any rights to go by the judicious addition of apple pulp, swedes, mangolds and what not. That is unless you grow your own fruit and make your own jam.”

S137 Preserves for all Occasions – April 1944

This book admits that it will soon become out of date as ingredients become more available after the war ut nevertheless it provide a lot of useful information on the varying ways of preserving food. Not just the expected jams and chutneys but syrups, bottling means of drying fruit, vegetables and herbs and how to store fresh produce for the longest time. Unlike other books on preserving that I own it doesn’t include recipes but instead concentrates on good techniques and means of avoiding common mistakes.

S138 Tree Fruit Growing – Pears, Quinces and Stone Fruits – December 1943

Volume 2 of Tree Fruit Growing concentrates much more on the individual varieties of a wider range of crops than I was expecting. I hadn’t realised that almonds were not true nuts but were in fact relative of the plum and peach where we eat the seed and discard the rest as a direct opposite to the two fruits. Bush admits to not having grown them himself and struggled to find any information but put together what he could. There is also a section on laying out an orchard and a substantial chapter on bees at the end along with the inevitable chapter on spraying for pests, a subject clearly on Bush’s mind a lot.

S140 Rabbit Farming – June 1944

Inspired by the success of ‘S101 Keeping Poultry and Rabbits on Scraps’ which as Goodchild explains in the introduction to this book was “giving all the practical hints I knew on rabbit keeping under wartime conditions in order that many newcomers could make a success of rabbit meat production”. This book on rabbit farming is however a very different work as it is aimed at a larger scale operation and includes use of the fur in coats and other clothes necessary to make a living from the business. Goodchild himself came from a long line of farmers and along with his partner ran the largest rabbit farm in England producing not just meat but from it’s manufacturing division coats, gloves and other assorted fur products. The photographs, presumably taken at his site near Crawley in south east England, show an extensive operation which must have been very useful to wartime food and clothing supplies.

S144 Poultry Farming – May 1945

The second of the books split off from ‘S101 Keeping Poultry and Rabbits on Scraps’ took almost a year longer to write than the first. Alan Thompson was amongst other things the editor of the monthly magazine ‘The Poultry Farmer’ which had started in 1874 as ‘The Fanciers Gazette’ and was eventually bought by the publishers of ‘Poultry World’ in 1968, so he was ideally suited to write the book. The book is not aimed at people wanting to keep a handful of chickens in their garden or allotment which was the point of S101 but instead those planning to run a commercial operation and early on mentions a figure of £2,000 (£73,500 in today’s money) for initial outlay if you want to have a hope of making a success of such a venture. The book goes into considerable detail not only on housing and selecting your chickens but also the finances of such an operation with several pages of photographs along with many line drawings to illustrate various points. My copy has clearly been well used.

S145 Trees, Shrubs and How to Grow Them – January 1945

Uniquely in this collection of eight books we have a title not covering food preparation or production and it is also, for me anyway, the least interesting of the titles. It goes into considerable detail about the various trees and shrubs in the UK, with guides as to what to plant and where, such as hedgerows and because Rowe is trying to impart so much information in a book just short of two hundred pages it is not particularly readable. That’s not to say it isn’t useful but just not for the general reader.

S146 The Vegetable Growers Handbook – Volume 1 – May 1945

All the other handbooks were commissioned by Penguin especially for this series and my copies are therefore true first editions whilst S146 and S147 are first editions in Penguin. The Vegetable Growers Handbook by civil servant Arthur J Simons however had first appeared in 1941 published by Bakers Nurseries Ltd of Codsall, Wolverhampton. Simons had written it during a period of quarantine he had undergone after contracting “a succession of childish but contagious diseases during the air raids”. In it you learn the basics of preparing the ground, improving the soil, using manure, compost and chemical fertilisers and this takes up the first third of the book. You then progress on what to grow, how to sow the seeds and raise the plants successfully initially in open ground and then a short section on using greenhouses and frames before a final chapter on pests and diseases and what to do about them. All in all a pretty comprehensive guide and I’m sure customers of Bakers Nurseries found it very useful.

S147 The Vegetable Growers Handbook – Volume 2 – May 1945

The second volume doesn’t have a first published date, but it doesn’t appear to be a Penguin original so I’m guessing this also first appeared from Bakers Nurseries. This volume deals specifically with the various crops you can grow, when to sow them and how to ensure a long cropping season with various vegetables ripening throughout many months. Like the first volume there are suggested plans for gardens or allotments to make maximum use of the space without wastage from gluts in certain weeks. Simons refers to letters he received after the first volume with suggestions which prompted this second book and despite the focus on wartime household needs these two books would even now be useful for a keen vegetable grower.

After the war it was decided to create a series of its own called Penguin Handbooks, the first new title of which was The Penguin Handyman which came out in November 1945 and was assigned the number PH9 with the obvious intention to move the existing eight books into this new series, however it all became more complicated than that, as it often does with Penguin Books. In fact PH1 is a 1945 reprint of ‘S119 Soft Fruit Growing’ but in the green cover of Penguin Handbooks rather than its original red. PH2 was assigned to the reprinted ‘S132 Tree Fruit Growing – Apples’ and PH3 became the reprint of ‘S138 Tree Fruit Growing – Pears, Quinces and Stone Fruits’, both of which are covered above and these would ultimately be combined into a single volume ‘PH83 Tree Fruit Growing’ in September 1962.

Despite the assumed plan of simply renumbering the existing handbooks into the gap left at the beginning of the new series we already have one book which hadn’t previously been issued as a handbook and just two of the originals occupying the first three numbers and this gets worse as numbers PH4 and PH5 were not in the end used and neither was PH8. This leaves just two numbers PH6 which became a reprint of ‘S145 Trees and Shrubs and How to Grow Them’ in 1951 and PH7 which combined S146 and S147 as the ‘Vegetable Grower’s Handbook’ in 1948.

Oddly ‘S137 Preserves for all Occasions’ did get reprinted as a ‘proper’ handbook as PH12 in July 1946, why they didn’t use one of the abandoned numbers I have no idea. ‘S140 Rabbit Farming’ and ‘S144 Poultry Farming’ were both discontinued in favour of their original base work ‘S101 Keeping Poultry and Rabbits on Scraps’ which came out as handbook PH14 in June 1949 making these two some of the most difficult to find Penguin Handbooks.