For November I’ve decided to read a selection of plays and the first one is The Frogs by Aristophanes. Normally I’m not a great fan of Ancient Greek dramas as you need a lot of knowledge of the gods and other characters involved but this translation is so readable I found myself laughing along as I read it. It was written in 405 BC and can be dated so precisely because it was created for drama competition as part of a festival honouring the god Dionysus in Athens where it took first place. Dionysus is one of the Greek gods with lots of jobs, according to the Wikipedia entry he is the god of the grape-harvest, wine making and wine, fertility, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre and it is in the latter one of these roles that a drama competition in his name becomes obvious.

The play tells the story of Dionysus deciding to travel to the underworld to bring back the playwright Euripedes who had died the previous year in order to rescue the arts in Athens back from the doldrums that he perceives it to be in. The first act sees Dionysus and his slave Xanthias on their journey, initially they visit Dionysus’s half brother Heracles for advice which causes him to collapse with laughter as Dionysus has decided to dress like Heracles with the lion head cloak and club but he really doesn’t have the build to carry off the look. Eventually they persuade Heracles to explain the route he used when he went to get the three headed dog Cerebus and they duly set off. When they meet Charon, the ferryman of the dead he agrees to take Dionysus and this is when he encounters the frog chorus who sing during the crossing. Despite the play being called The Frogs this is the only time they appear in it. After various encounters with people who think Dionysus is Heracles and either hate him for taking Cerebus or love him for it they finally reach the home of Pluto ruler of the Hades.

Act two takes place entirely at the Pluto’s house where they find Euripedes and also another dramatist Aeschylus who had died about 50 years earlier. These two had been arguing for the last year about which was the better writer and should therefore sit with Pluto for meals. Dionysus takes it onto himself to judge a contest between them and they take it in turns to be rude about the others works with the chorus commenting as though it was a fight with each man landing viscous blows on the other. This gives Aristophenes a chance to parody each of the two dramatists styles and throw in his own critical comments on both of them. Eventually Pluto gets fed up and decides to determine the winner via a special set of scales which can measure the weight of an argument. Each man gets to speak one line into the baskets on the scale and they are marked against one another with the scale, to Euripedes’s annoyance Aeschylus wins both attempts by mentioning heavier objects. In the end Dionysus decides to simply ask the two dramatists for advice to save Athens, Euripedes has lots of fine words but Aeschylus has more practical suggestions so instead of having Euripedes brought back to life he decides on Aeschylus. A final parting shot from Aeschylus is to insist that Sophocles should have the seat as the finest dramatist rather than Euripedes.

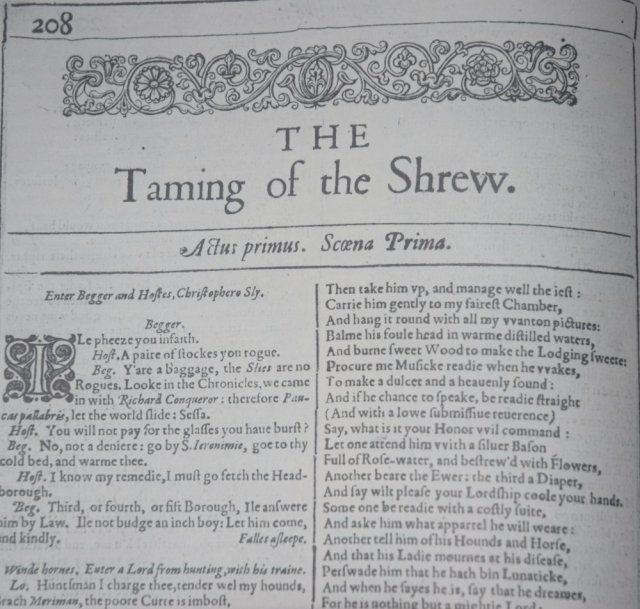

Translations of ancient Greek and Latin have become far ‘less stuffy’ over the last few decades and this can largely be thanks to Penguin Books who started their series of Penguin Classics in 1946 with the express intent of making the classics more approachable. Compare this extract from the Harvard Classics edition of 1909 which is available on Project Gutenberg, which deals with the god Dionysus rowing across the Styx with Charon and encountering the Frog chorus. The specific translator is not given for this edition on the site as this was a massive group exercise resulting in 51 volumes of a wide selection of classic works.

FROG CHORUS Brekekekex, ko-ax, ko-ax! Brekekekex, ko-ax, ko-ax! We children of the fountain and the lake Let us wake Our full choir-shout, as the flutes are ringing out, Our symphony of clear-voiced song. The song we used to love in the Marshland up above, In praise of Dionysus to produce, Of Nysaean Dionysus, son of Zeus, When the revel-tipsy throng, all crapulous and gay, To our precinct reeled along on the holy Pitcher day. Brekekekex, ko-ax, ko-ax. DIONYSUS. O, dear! O dear! now I declare I've got a bump upon my rump.

The same passage from the 1964 translation by David Barrett printed by Penguin and reprinted in the edition I have been reading.

FROGS Brekeke-kex, ko-ax, ko-ax, Ko-ax, ko-ax, ko-ax! Oh we are the musical Frogs! We live in the marshes and bogs! Sweet, sweet is the hymn, That we sing as we swim, And our voices are known. For their beautiful tone, when on festival days We sing to the praise Of the genial god - And we don't think it odd When the worshipping throng, To the sound of our song, Rolls home through the marshes and bogs. Brekekex! Rolls home through the marshes and bogs. DIONYSUS. I don't want to row any more. FROGS. Brekekex! DIONYSUS. For my bottom is getting so sore.

As you can see the Penguin edition is considerable more ‘lively’ and the translator has almost turned to the poetic structure of the limerick in order to emphasise the comic nature of the play. This is a form that he will return to several times during the translation in some places using the limerick itself. The play is only 110 short pages so I read it in two sittings, the edition is from the Little Black Classics series by Penguin and is one of the most expensive of these books at £2. I’m looking forward to reading more from this series of titles in the coming months.