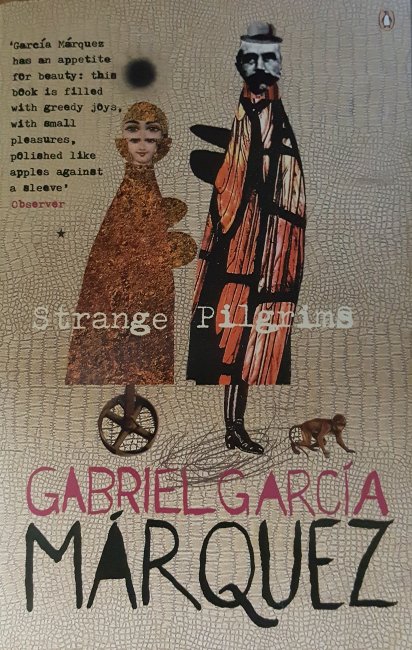

For my 100th post on this blog I have chosen one of the lesser known works by Gabriel García Márquez, in fact it is his last published collection of short stories. They were started during the 1970’s and 80’s but were not actually published until 1992 with an English translation appearing a year later. My copy is the Penguin books edition translated by Edith Grossman and published in 1994 with a bizarre cover by Matthew Richardson of Eastwing Design. The twelve tales are linked by being all about Latin American characters travelling or living in Europe, this was a familiar position for Márquez at the time as he lived in Barcelona for seven years in the 1970’s, going there after the success of his novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude”.

Born in Columbia, Márquez spent a lot of his life in Mexico, although his time in Europe clearly had a significant influence on these works. Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 he is probably best known for his novels, three of which are also on my shelves along with three more books of short stories. However because there are so many reviews of his novels such as “Love in the Time of Cholera”and “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and also as I have a soft spot for well crafted short stories this collection had to be the one to read this week.

In the preface Márquez explains the long gestation of these stories, beginning with an exercise book in which he wrote sixty four tales none of which he was quite happy with, the dates each story was started is given after each one in the book and I have added this information as a date in brackets after each title below. He had several goes at rewriting but was never satisfied and the book was added to his papers to be looked at again when he might have a better idea how to work with the material. Unfortunately the exercise book got lost, presumably thrown out by accident, so he had a go at recreating them from memory. This reduced the total to about thirty and he is sanguine about this regarding the other half as clearly not good enough if he couldn’t remember how they went. The stories were still not right though and it was not until a final eight months of solid work finished the last ten included in this collection, which were all worked on simultaneously, that he finally had a book that he was happy to publish in the early 1990’s.

The twelve stories are each briefly reviewed below:-

Bon Voyage, Mr President (June 1979)

The first story concerns a familiar subject for Latin America, that of a deposed and exiled president finding treatment for illness in a foreign country, in this case Geneva in Switzerland. He is recognised by one of the ambulance drivers who comes from his original country and the driver plans along with his wife to get money from him by selling a fake insurance and funeral plan. The plot does not go as they intended and the development of the three characters makes an interesting twist.

The Saint (August 1981)

The Saint in the story is the incorruptible body of a seven year old girl from Columbia being taken round Rome by her father in an attempt to have her recognised as a saint. Well that is the initial premise anyway. In truth the story is more about the various characters staying in the hostel near the Vatican and their inter-reactions not only with each other, the saint and oddly the lion in the nearby zoo. The final two sentences of the tale though switch the meaning of the title in an unexpected way.

Sleeping Beauty and the Airplane (June 1982)

I’m not sure what to make of this story, it has a distinct voyeuristic tone that can be a little uncomfortable. The narrator sees a beautiful woman in Charles de Gaulle airport, Paris and then is pleased to see that he has the seat next to her on the plane to New York. The descriptions of watching her sleep next to him throughout the flight without any communication taking part between them throughout the journey makes odd reading.

I Sell My Dreams (March 1980)

Another tale regarding sleep, although this time the prophetic dreams of a Colombian woman who had come to Europe as a child and is first encountered by Márquez in Vienna. He sees her again many years later in Barcelona when he meets the Chilean poet Pablo Naruda and she is in the same restaurant and she is still making money from her dreams.

“I Only Came to Use the Phone” (April 1978)

The most disturbing story in the collection. A woman is driving on the way to Barcelona in a storm when her car breaks down. She is eventually picked up by a bus which drops her off at its destination so that she can use the phone. However the rest of the passengers are female mental patients and it is assumed at the asylum that she must also be a patient and she is prevented from calling her husband, sedated and admitted. The story describes her ultimate mental collapse as she tries and fails to explain her true situation.

The Ghosts of August (October 1980)

At less than four full pages this is the shortest work in the collection and is a really good ghost story, this time set in Tuscany and again involving a real person, in this case Venezuelan writer Miguel Otero Silva.

María dos Prazeres (May 1979)

Maria is a semi-retired prostitute in her seventies, originally from Manaus in Brazil but living for most of her life in the Gracia district of Barcelona. She now has only one client who has come to her weekly for decades and it is more a relationship than a business proposition. Convinced she is soon to die the story concerns her elaborate plans for her funeral and what is to happen with her belongings including her little dog afterwards. You really get to know her as the story unfolds and just as with other stories in this collection things suddenly change at the end.

Seventeen Poisoned Englishmen (April 1980)

The eponymous Englishmen are simply bit players in this tale of a Colombian widow who has travelled to Italy planning to see the Pope soon after the end of WWII. What it is more about is her reactions to post war Naples and her fears when she has to make her own way rather than the planned help she was expecting.

Tramontana (January 1982)

The Tramontana of the title is a persistent and powerful wind that the narrator of the tale experienced for three long days whilst staying in Cadaqués in Catalonia. He describes it as oppressive presence taking a personal affront to the presence of him and his family. It also clearly has a strong effect on all those who experience it.

Miss Forbes’s Summer of Happiness (1976)

Two young boys from Alta Guajira on the Colombian Caribbean coast are on the island of Pantelleria at the southern end of Sicily for a long summer holiday. For the first month they were with their parents and all was wonderful but they had left them in the care of a German governess called Miss Forbes whilst they went on a writers retreat elsewhere in the Mediterranean. She is very strict and the holiday had become intolerable to the boys, so much so that they resolve to kill her but the plot does not go as they intended…

Light is Like Water (December 1978)

This very short tale (around five pages) is positively surreal and again features two young boys around the ages that Márquez’s children would have been when he started to write it. As the narrator explains, he was asked how the light came on at a touch of the switch and replied “Light is like water, you turn the tap and out it comes”. Taking this seriously the boys break a bulb and sail a boat on the pool of light that cascades out of it despite being in an apartment on the fifth floor of a building in Madrid. But you should never play with liquid light.

The Trail of Your Blood in the Snow (1976)

Like the boys in ‘Light is Like Water’ the protagonists of this final tale are originally from Cartegena de Indias on the Colombian Caribbean coast but this time they are wealthy young adults recently married and travelling from Madrid to Paris overnight in a Bentley convertible that had been a wedding present. But Nena has cut her finger on a rose thorn and the bleeding will not stop.

A very enjoyable collection and if you have never read any Márquez it’s a good place to start. The stories do all feel that they belong together, possibly due to the simultaneous final rewriting yet are sufficiently different to highlight alternate aspects of his style. Highly recommended.