Although the longest essay I have written here so far, this is just a brief introduction to a very attractive series of books produced by Penguin from 1939 to 1959. Covering a vast array of subjects with (for the most part) excellent illustrations in both black and white and colour they make up a mini reference library all on their own.

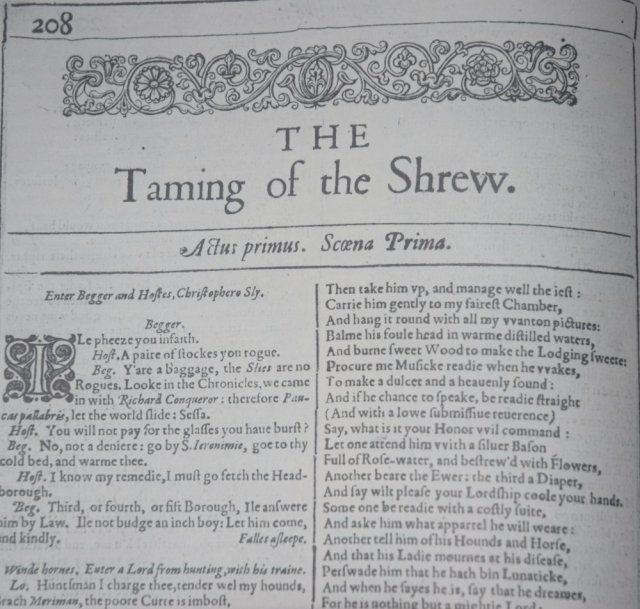

Starting a new series of illustrated hard back books just as war had broken out was clearly just bad timing for Penguin Books, they had been planned for months and the first two were ready to go for November 1939. That the series not only survived the subsequent paper rationing but flourished for a further 74 volumes until 1959 was nothing short of a miracle. Almost all the books have the same format, a monograph on the specialist subject which may also include black and white line illustrations or photographs, followed by a series of colour plates. The monograph averages about 30 pages; although Ur by Sir Leonard Woolley has only 18 and at the extreme opposite A Book Of English Clocks by R.W. Symonds has 74 pages of text. Likewise the colour plates were intended to be on 16 pages, this also varies but by no means as much as the texts as this was easily the most expensive part of each production so costs were closely monitored.

Starting a new series of illustrated hard back books just as war had broken out was clearly just bad timing for Penguin Books, they had been planned for months and the first two were ready to go for November 1939. That the series not only survived the subsequent paper rationing but flourished for a further 74 volumes until 1959 was nothing short of a miracle. Almost all the books have the same format, a monograph on the specialist subject which may also include black and white line illustrations or photographs, followed by a series of colour plates. The monograph averages about 30 pages; although Ur by Sir Leonard Woolley has only 18 and at the extreme opposite A Book Of English Clocks by R.W. Symonds has 74 pages of text. Likewise the colour plates were intended to be on 16 pages, this also varies but by no means as much as the texts as this was easily the most expensive part of each production so costs were closely monitored.

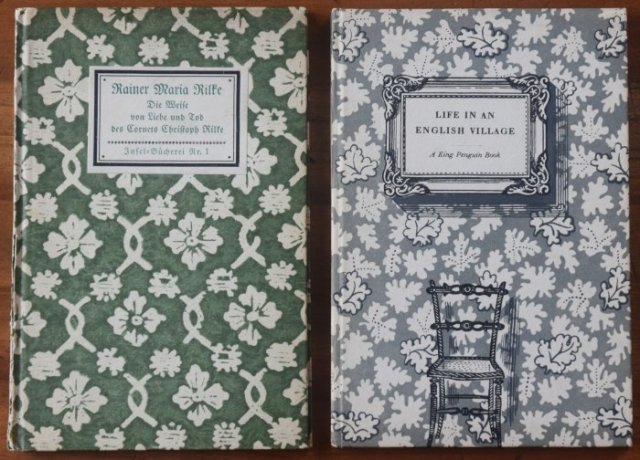

Kings were inspired by the German Insel Bucherei printed by Insel Verlag, these beautiful art books had started in 1912 and by the time Penguin launched their Kings there were roughly 500 Insels already available and their catalogue would eventually reach 1,400 different titles. Fortunately for my bookshelves Kings stop at number 76 although there are a few variations to collect as well but my complete set of the first editions is shown in the picture at the top of this essay. One of the most striking aspects of that picture is the wide variety of covers and the design of these was seen as one of the most important aspects of the series. After all they have to draw the potential purchaser in, especially as these were initially priced at one shilling or twice the price being charged for the normal Penguin paperbacks. Unfortunately this didn’t last very long as the price very quickly doubled as it became clear that they were more expensive to do right that initially anticipated and Alan Lane wanted them to be done as well as Penguin could manage. This meant that they really had to look striking so the original house style on the first five was quickly dropped.

Only seventeen Kings were ever reprinted or revised, so with almost all of them the first edition is the only example available and on average 20,000 were printed of each title, although A Book of Toys sold over 55,000 copies. This means that Kings are not normally particularly rare; but are scarce enough to make the hunt trying to collect them all interesting. Some such as Magic Books From Mexico were recognised as niche interests from the start so the print runs were commensurately smaller. In the case of this book however even these apparently didn’t sell and there is a rumour that a large number of them had their plates removed and put under glass in the type of coffee table very popular in the 1960’s and 70’s.

K1 – British Birds on Lake, River and Stream by Phyllis Barclay-Smith – Nov 1939

K2 – A Book of Roses by John Ramsbottom – Nov 1939

K3 – A Book of Ships by Charles Mitchell – Sept 1941

K4 – Portraits of Christ by Ernst Kitzinger & Elizabeth Senior – Feb 1941

K5 – Caricature by E.H. Gombrich & E. Kris – Feb 1941

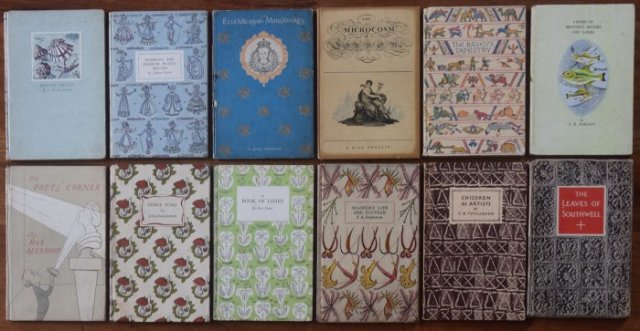

The first five Kings produced under the editorship of Elizabeth Senior are highly distinctive, although the actual printing quality is not as good as it might be given the intention to emulate the Insel books. However as you can see from the dates of first publication this was not a time for finesse, wartime restrictions soon caused problems with the series meaning that a large proportion of K3, K4 and K5 were bound in soft card covers cut flush to the internal pages as well as the overlapping boards normally used for Kings. The Book of Ships in the picture above is one of these soft back editions and as can be seen is consequently slightly smaller than the other four. K1 is the first of these volumes to use plates from John Gould‘s famous work The Birds of Great Britain, the other being K19 Garden Birds. A Book of Roses (K2) also makes use of a famous earlier work for the plates, in this case Redouté‘s Les Roses. The other three volumes use 16 colour plates from a mixture of sources and along with these there are several black and white images within the text. K1 and K2 only have the 16 colour plates along with a single black and white portrait of Gould and Redouté respectively.

Sadly Elizabeth Senior was killed in an air raid in 1941 and editorial control of the series passed to Nikolaus Pevsner

K6 – British Shells by F. Martin Duncan – June 1943

K7 – Fashions and Fashion Plates 1800-1900 by James Laver – June 1943

K8 – Elizabethan Miniatures by Carl Winter – June 1943

K9 – The Microcosm of London by John Summerson – June 1943

K10 – The Bayeux Tapestry by Eric Maclagan – Dec 1943

K11 – Fishes of Britain’s Rivers and Lakes by J.R. Norman – Dec 1943

K12 – The Poets’ Corner by John Rothenstein – Dec 1943

K13 – Edible Fungi by John Ramsbottom – July 1944

K14 – A Book of Lilies by Fred Stoker – Dec 1943

K15 – Seashore Life and Pattern by T.A. Stephenson – July 1944

K16 – Children as Artists by R.R. Tomlinson – Dec 1944

K17 – The Leaves of Southwell by Nikolaus Pevsner – Dec 1945

After the fairly dull cover design of the first five with its fussy white banding round the spine it is a relief to see the variety produced in the next dozen. Half of them have that Insel Bucherei look with the title and author appearing on a reproduction of the paste down labels quite common on quality books from the previous 100 or so years. Unlike Insel books this is actually part of the printed design rather than an extra slip, but it does give a touch of class to the book. The first few are experimenting with alternate cover styles and Fishes of Britain’s Rivers and Lakes is a very attractive design by Charles Paine, I’m less impressed with the cover of Microcosm of London with it’s overly florid text done by Walter Grimmond. Having said that Microcosm is the first of the Ackermann editions in Kings. Rudolph Ackermann was a bookseller and printer in London in the early 1800’s and his books and prints sold well making him known for the quality of his images which captured not only cityscapes like this along with K59 Cambridge and K69 Oxford but also the images documenting the start of the railway age some of which are included in K56 Early British Railways and for further variation K46 Highland Dress, all plates of which were originally printed by Ackermann.

Other notable books in this block of twelve are K10 The Bayeux Tapestry with 8 pages of colour plates and 40 pages of black and white photographs which at the time were some of the best images available in print. K13 Edible Fungi is beautifully illustrated by Rose Ellenby who also did its pair K23 Poisonous Fungi. Like Elizabeth Senior, Nikolaus Pevsner got one of his own titles in this block with K17 The Leaves of Southwell which has 32 pages of lovely black and white photographs of the capitals and columns in the chapter house at the Minster of Southwell in Nottinghamshire.

K18 – Some British Moths by Norman Riley – May 1945

K19 – Garden Birds by Phyllis Barclay-Smith – May 1945

K20 – English Ballet by Janet Leeper – Dec 1944

K21 – Popular English Art by Noel Carrington – Dec 1945

K22 – Heraldry in England by Anthony Wagner – Nov 1946

K23 – Poisonous Fungi by John Ramsbottom – Dec 1945

K24 – Birds of the Sea by R.M. Lockley – Dec 1945

K25 – Ur: The First Phases by Sir Leonard Woolley – May 1947

K26 – A Book of Toys by Gwen White – Dec 1946

K27 – Flowers of Marsh and Stream by Iola A. Williams – Nov 1946

K28 – A Book of English Clocks by R.W. Symonds – May 1947

K29 – Flowers of the Woods by Sir E.J. Salisbury – Apr 1947

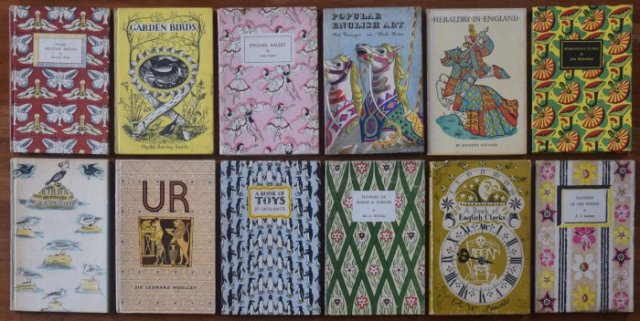

Apart from the obviously wonderfully choice of getting somebody called Leeper to write a book about ballet this is a delightful mix of titles. K18 British Moths goes back to the first two Kings by using prints from an old classic book on the subject, in this case by Moses Harris from the mid 1700’s. K21 Popular English Art is an eclectic mix from drawings of Windsor chairs to colour images of a jug, ship’s figurehead and even a pub interior all done by Clarke Hutton who like Noel Carrington who wrote the text is probably best known to Penguin collectors for their work on Puffin Picture books. Birds of the Sea is also illustrated by an artist in Puffin Picture Books, R.B. Talbot Kelly who created the PP52 Paper Birds which was a cut out book now rarely seen in one piece along with the beautiful PP65 Mountain and Moorland Birds.

One of my favourite King Penguins comes next, K26 A Book of Toys by Gwen White, it’s one of the oddities in the range as it deviates from the plan of a monograph and plates being illustrated all the way through much more like a small hardback Puffin Picture Book with the handwritten text drawn directly onto the plates and not typeset; and what is not to like about a cover with dozens of toy penguins. K27 is let down badly by the quality of the printing of the colour plates, K28 is frankly a mess with far too much jammed into the book which would have been better expanded as a Pelican Book and dropped from this series but K29 rescues this block with some lovely if rather flat coloured plates.

K30 – Wood Engravings by Thomas Bewick by John Rayner – Apr 1947

K31 – English Book Illustration 1800-1900 by Philip James – Sept 1947

K32 – A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens – Dec 1946

K33 – Russian Icons by David Talbot Rice – Oct 1947

K34 – The English Tradition in Design by John Gloag – Oct 1947

K35 – A Book of Spiders by W.S. Bristowe – Sept 1947

K36 – Ballooning by C.H. Gibbs-Smith – Nov 1948

K37 – Wild Flowers of the Chalk by John Gilmour – Dec 1947

K38 – Compliments of the Season by L.D. Ettlinger & R.G. Holloway – Dec 1947

K39 – Woodcuts of Albrecht Durer by T.D. Barlow – Sept 1948

K40 – Edward Gordon Craig by Janet Leeper – Oct 1948

K41 – British Butterflies by E.B. Ford – Oct 1951

The first two of this block make a great pair, they have a similar design with high quality illustrations right through the text as well as the plates at the back and K39 Woodcuts of Durer goes well with the both of them. That brings us to another King Penguin oddity. K32 A Christmas Carol is almost a facsimile of the original first edition of this Dickens classic, it doesn’t count as a true facsimile as the font used is Monotype Modern, it being the closest available to match the original. The very interesting Russian Icons by David Talbot Rice is another book let down by the poor quality of the printing of the plates, it also has a correction slip pasted over credit for the cover illustration. William Grimmond is credited on the page with Enid Marx pasted over the top. The English Tradition in Design has 72 pages of black and white photographs, the cover of this book does tend to fade badly, probably more than any other King Penguin whilst Wild Flowers of the Chalk, Compliments of the Season and British Butterflies all go back to the original internal plan with a monograph followed by 16 plates which was now becoming a rarity in the series, even if only the last one had a suitable cover design.

K42 – British Military Uniforms by James Laver – Oct 1948

K43 – A Prospect of Wales by Gwyn Jones – Sept 1948

K44 – Tulipomania by Wilfrid Blunt – Oct 1950

K45 – Unknown Westminster Abbey by Lawrence E. Tanner – Nov 1948

K46 – Highland Dress by George F. Collie – Aug 1948

K47 – British Reptiles and Amphibia by Malcolm Smith – June 1949

K48 – A Book of Scripts by Alfred Fairbank – Nov 1949

K49 – Some British Beetles by Geoffrey Taylor – June 1949

K50 – Popular Art in the United States by Edwin O. Christensen – June 1949

K51 – Life in an English Village by Noel Carrington – June 1949

K52 – The Isle of Wight by Barbara Jones – July 1950

K53 – Flowers of the Meadow by Geoffrey Grigson – June 1950

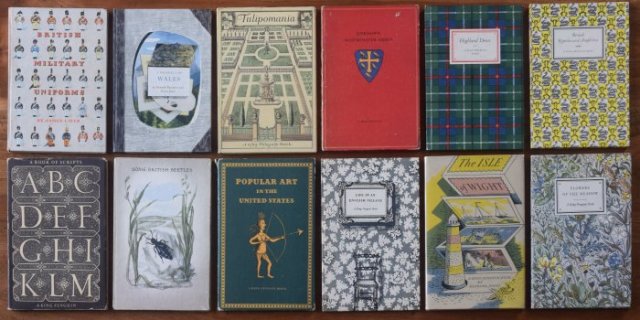

By now Swiss designer Jan Tschichold was firmly in control of the Penguin house style, he had started with tidying up the look of the major series and setting firm rules not just on typography but also strict design specifications, his influence can now be seen in the Kings. His re-imposition of the original plan of monograph with 16 plates continued with these dozen, just two don’t fit this general structure although the number of plates did get up to 22 for some. The two that don’t fit are K45 Unknown Westminster Abbey along with K48 A Book of Scripts, K45 is very similar in structure to K17 The Leaves of Southwell which makes sense as these are covering much the same field just a different building. A Book of Scripts is another King oddity, concentrating as it does on fine handwriting and to do this it needs lots of illustrations, it also is the only King Penguin to be revised/reprinted four times. Beyond that record it was later greatly enlarged and printed in February 1969 as a large format Pelican (A973) which also went to several reprints.

Largely this gives an idea as to what Kings could have been if there had been more money, better quality printing and greater control on the design from the beginning. The problem was the price that they now had to be sold at. From 1940 to 1949 they had been either 2 or 2½ shillings, by 1952 the price had rocketed and they were just under 4½ shillings and two years later they had reached 5 shillings. They are truly lovely books though, watercolours by Kenneth Rowntree show Wales at its best with K43, Edward Bawden took on the English village (K51) in his distinctive style whilst Barbara Jones not only beautifully illustrated K52 The Isle of Wight but unusually also wrote the monograph. Tulipomania uses plates by Alexander Marshall from a collection from the 1650’s and now in the Royal collection in Windsor. These are some of the most vibrant flower paintings in the King series and makes this a highly desirable book in its own right. The other great joy of this dozen is K49 Some British Beetles illustrated by Vere Taylor.

K54 – Greek Terracottas by T.B.L. Webster – Apr 1951

K55 – Romney Marsh by John Piper – May 1950

K56 – Early British Railways by Christian Barman – May 1950

K57 – A Book of Mosses by Paul W Richards – July 1950

K58 – A Book of Ducks by Phyllis Barclay-Smith – Apr 1951

K59 – Ackermann’s Cambridge by Reginald Ross Williamson – June 1951

K60 – The Crown Jewels by Oliver Warner – June 1951

K61 – John Speed’s Atlas of Tudor England and Wales by E.G.R. Taylor – June 1951

K62 – Medieval Carvings in Exeter Cathedral by C.J.P. Cave – May 1953

K63 – A Book of Greek Coins by Charles Seltman – Nov 1952

K64 – Magic Books from Mexico by C.A. Burland – Feb 1953

K65 – Semi-Precious Stones by N. Wooster – May 1953

Jan Tschichold only lasted a couple of years in his role at Penguin but in that time he completely revolutionised the house style. His replacement was the German Hans Schmoller, he took Tschichold’s templates and refined them further. In this batch we can see the continuation of the original Insel inspired cover designs with fake paste-down label on the majority. The cover of K61 John Speed’s Atlas is based on an old copy which is highly appropriate for this collection of county maps from 1627, the title reflects the usual name for this group of maps although they were not actually by the great Tudor English cartographer but rather his Dutch contemporary Pieter van den Keere. The cover of K63 A Book of Greek Coins is another Walter Grimmond design, he did fifteen in all and only two (K59 Ackermann’s Cambridge and K64 Magic Books from Mexico) come close to looking like the original plan. A further oddity of K63 is one of the coins on the cover, which are intending to show the development of the Britannia figure all the way from an original Greek version to the present day. Grimmond includes a penny with the date 1952 in the bottom left as that was the printing date of the book, however no pennies were actually minted that year as there were plenty already in circulation.

K55 Romney March written and illustrated by the artist John Piper is a very attractive volume, although his sketches illustrating the section on churches in the area are for me more compelling than the 16 colour plates at the back. Also sticking strictly to the 16 plates rule are K57, K58, K60, K64 and K65 with K58 A Book of Ducks and K65 Semi-Precious Stones being particularly fine. K62 Medieval Carvings in Exeter Cathedral continues the style set by the other three books in this sub series of medieval carvings (K17, K45 and K72) all of which have a large collection of black and white photographs, by in this case having 64 pages of them. One extra oddity that should be covered at this point is the soft back Mexican reprint of K64 by Ediciones LARA produced in 1966 to coincide with the Mexico Olympics, although not printed by Penguin it was fully authorised by them as stated inside.

K66 – Birds of La Plata by W.H. Hudson & R. Curle – Apr 1952

K67 – Mountain Birds by R.A.H. Coombes – Nov 1952

K68 – Animals in Staffordshire Pottery by Bernard Rackham – Sept 1953

K69 – Ackermann’s Oxford by H.M. Colvin – Mar 1954

K70 – The Diverting History of John Gilpin by William Cowper – Nov 1953

K71 – Egyptian Paintings by Nina M Davies – May 1954

K72 – Misericords by M.D. Anderson – Oct 1954

K73 – The Picture of Cricket by John Arlott – May 1955

K74 – Woodland Birds by Phyllis Barclay-Smith – Nov 1955

K75 – Monumental Brasses by James Mann – Nov 1957

K76 – The Sculpture of the Parthenon by P.E. Corbett – July 1959

The final batch of Kings took a long time to come out certainly compared to the rapid fire production of earlier years. K66 Birds of La Plata is the only bird book in the series not to feature British birds but rather those of South America following an interest Sir Allen Lane (the founder of Penguin) had developed during his time in that continent at the end of WWII whilst trying to launch Penguin Books there. K70 John Gilpin has also strong links to Lane as it is a heavily reduced in size version of a book he had privately printed as a limited edition Christmas gift the previous year. To emphasise the unusual nature of K66, K67 Mountain Birds is actually called British Mountain Birds inside.

Again 16 colour plates is the norm with only John Gilpin (as a reprint of an existing book), K72 Misericords with lots of photographs (as noted above to match others in the sub series) and the final two books K75 Monumental Brasses and K76 The Sculpture of the Parthenon not matching that pattern. K71 Egyptian Paintings is a little disappointing, the colours are very muted in the reproductions and don’t have the vibrancy of the original tomb paintings. All three bird books are lovely things and would with their compatriots through the Kings make a very attractive collection on their own with the advantage that with the exception of K66 La Plata they are all quite easy to find. K75 Monumental Brasses was a surprise when I first got a copy, I was expecting more black and white photographs but instead this book is illustrated with drawings that have been coloured a pale yellow and very nice they are too as they are certainly clearer that photographs might have been. This is particularly true of the final book in the set; K76 is a sad end to a great series, the photographs are poorly printed compared to previous works and the text is hardly a gripping read

The animation below showing some of the wonderful plates from various King Penguins was done for a talk on the Gentle Art of Penguin Collecting given by myself and Megan Prince at The 2018 Hay Independence celebrations. I hope this inspires a collector or two out there to take a look at the 76 King’s almost 60 years after the last one was printed, they are well worth dipping into.